Opening the door on 19th century rural life

It's the break of day. Inside the kitchen of a cramped, two-room house, polenta is being cooked over an open fire, filling the kitchen with smoke.

A few people huddle around the burning embers: an old woman sits on a wooden bench, a man and a couple of barefoot toddlers stand. The door is kept ajar to let out the choking fumes.

This is the type of 19th century scene that unfolded at the start of each day in villages of upper Ticino – the Sopraceneri.

In this case, the house is in Cugnasco, just east of Locarno at the bottom of the Val Verzasca. Or at least that was where it originally stood.

The Cugnasco house is one of three rural buildings from Ticino that were disassembled, stone by stone or plank by plank, and transported north to Switzerland’s open-air museum, Ballenberg, where they have been reconstructed.

The pots hang again from the low ceiling; the cutlery – consisting of a bread knife and not much else – is back on the fold-down, wooden table.

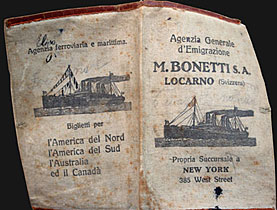

Giovanni Buzzi, an expert on the history of rural Ticino, recounts what life must have been like around 1850 – the start of the first wave of mass migrations overseas.

“The diet was very poor and monotonous. There was polenta [porridge-like dish made from boiled cornmeal] and bread made from rye,” he says. “They had chestnuts to see them through the winter months, and potatoes. The chestnuts were dried and either ground to make flour or cooked in water or milk.

“I got to know an old man and when I told him I liked chestnuts, he replied, ‘oh, don’t mention them. We had nothing to eat but chestnuts for three months at a time. I can’t look at them anymore’.”

Under many roofs

A typical family was made up of five to ten people – adults and their children, an unmarried aunt or two, an uncle and perhaps a grandparent who had reached the ripe old age of 40.

But they rarely lived under one roof.

Children from the age of five and other young people, Buzzi explains, would have moved between the various primitive structures tending the livestock – consisting of a couple of cows, sheep and a goat – only coming to the main house in the village a few times a year.

“I calculated that in Malvaglia in Blenio valley a family had between five and ten buildings, and 20-30 small parcels of land spread across the plain, the mountain slopes and high alpine pastures.”

Even though conditions were primitive, daily life was governed by a complex set of rules. There were statutes regulating how most of the land – held in common by the villagers – was to be used, who could use it and when, such as the day in late spring or early summer a family was permitted to take its livestock up into the mountains to graze.

Chestnut fight

Chestnut groves were normally common property but the individual trees were privately owned, with a single tree sometimes belonging to several families. “As many as five families could feed themselves from the fruit of one tree. They often fought over every chestnut,” Buzzi says.

The wooded slopes were also part of the common lands but deforestation was a problem in the 19th century as the villages exported most of the timber to northern Italy where it was used as fuel to feed the factories of industrialised cities like Milan.

Families generated a meagre income by exporting the cheese made from the milk of their livestock as well as the butchered meat from the animals.

One cow was kept at the main house to provide milk for the children and older people.

“They used the little money they had to buy material for clothes or salt, which was important. It really wasn’t a money economy,” the expert adds.

Illiterate

Buzzi says infant mortality was about 50 per cent, and most children who survived did not have the privilege of going to school and were therefore often illiterate. The few schools that existed were run by the village priest but not many of these men of the cloth were capable teachers.

Property was divided among all of the children. So as not to have to divide up too much the few parcels of privately owned land a family possessed, strategies were developed: A son was married off to a girl in another village or money was borrowed to pay for another child to emigrate.

Back inside the Cugnasco house, day turns to night and everyone moves upstairs to sleep in the single room above the kitchen. Buzzi concludes his story:

“They slept in their clothes because they didn’t have undershirts or nightshirts. Two or three children would share a bed, and in that way, they were each other’s ovens or hot water bottles.”

swissinfo, Dale Bechtel

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.