Picasso’s erotic obsessions revealed

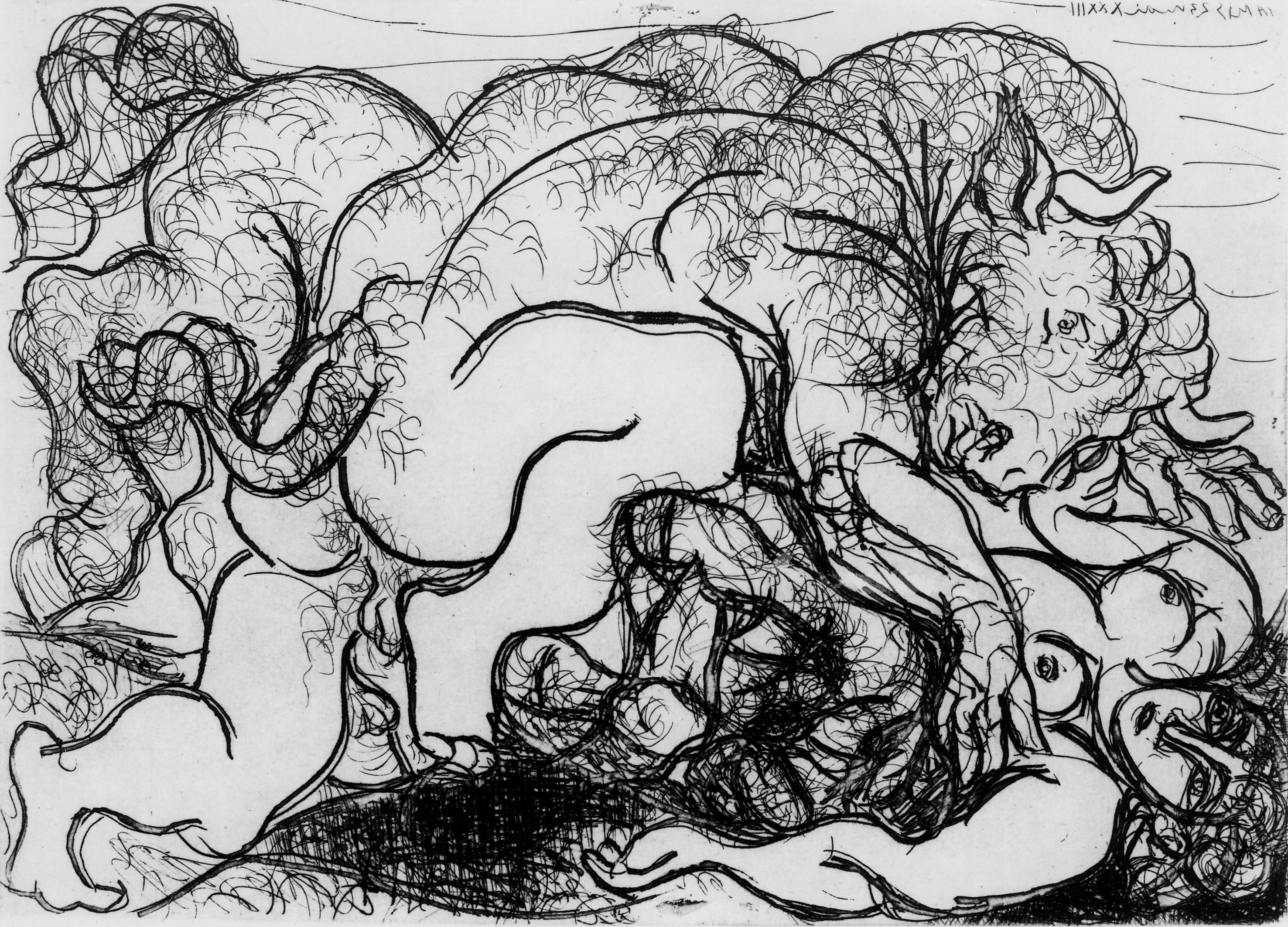

Women, passion and sex were subjects that were often on the mind of the artist Pablo Picasso – and they form the basis of an exhibition in Bern.

Picasso: The Power of Eros at the Museum of Fine Arts Bern brings together around 100 of the 20th century master’s prints from the vast collection of a Zurich industrialist.

At the entrance of the exhibition, which runs until May 1, hangs a panel listing the most important women in the Spanish artist’s life: Fernande Olivier, Olga Koklova, Marie Thérèse Walter, Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot and Jacqueline Roque.

Added to this, of course, are all those other women of his imagination and memory who appear in his works as historical or mythical figures or as prostitutes in brothels.

Throughout all his stylistic periods there seems to be one common topic: desire, or to put it more bluntly: sexuality, crude or sensual, symbolic or grotesque.

The rich textile industrialist Georges Bloch (1901-1984) started collecting Picasso’s prints in 1920, but only met the artist in 1953. They became friends, which enabled Bloch not only to expand his collection but normally to get the number one print in the run.

By Picasso’s death in 1973, Bloch had acquired around 2,000 items, including linocuts, woodcuts, etchings, copperplate engravings, dry points, aquatints and lithographs.

Around 500 of these works were given to the Gottfried Keller Foundation for art and then deposited in eight museums in Switzerland, including the one in Bern, on one condition: the museums should, in turn, present a selection of the bequest to the public every five years.

Fighting and sex

“Each time we look for a specific angle. Last time it was bull fighting. This time we have concentrated on erotic scenes,” said Therese Bhattacharya-Stettler, the exhibition’s curator.

It should be noted, that, with Picasso, bull fighting and sexuality are not always mutually exclusive.

Picasso often treated sexuality irreverently. In 1905 he produced his Saltimbanques series of prints, one of which shows an ironic depiction of Salomé’s dance before Herod. Salomé is ugly and scrawny. Herod slouches. A musician holds a child as if it were a violin.

The artist, playing on sex and humour, pays scant respect to major episodes in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Other prints draw on Greco-Roman mythology, with satyrs with cloven hooves, and – of course – the minotaur, the creature with the head of a bull and the body of a man.

Women

“Picasso was a fan of corridas [bullfighting],” said Bhattacharya-Stettler. “The corrida represents masculinity and fighting. For him, it was also a fight with women – the two merged.”

“Here you can see a ‘fight’ with a woman which is also an embrace,” said the curator, pointing to the work Minotaur attacking an Amazon, from 1933.

In his print output – which increased towards the end of his career – Picasso used a different technique from that in the rest of his oeuvre. But the same themes crop up in the artist’s paintings and drawings.

The minotaur, for example, can be seen elsewhere, as can Celestina, the old procuress inspired by the late 15th century Spanish novel Calisto and Melibea by Fernando de Rojas. The voyeur is also a regular motif, more often than not, in brothels.

“Degas also painted brothel scenes. In fact, Picasso collected Degas monotypes and this was a source of inspiration for him,” said Bhattacharya-Stettler. “He admired Degas and also put him in some of his works.”

“Art is never chaste”

Another favourite setting: the artist’s atelier, home to the strange – and voyeuristic – link between the painter and his model. “Art is never chaste,” Picasso once said. He had a particular fascination with the painter Raphael and his mistress, La Fornarina.

The setting is found in some of the so-called 347 series, dating from 1968. “Picasso uses an Ingres painting as a basis, in the background of which you can also see a voyeur, and he interprets this in his own way,” Bhattacharya-Stettler explained.

In his work, Picasso is watching Ingres, watching Raphael frolicking with his mistress, a painting which needs to be looked at in detail before its message becomes apparent.

What with the recent Erotic Rodin exhibition at the Fondation Gianadda in Martigny and now in Bern Picasso and Eros, perhaps the veil of hypocrisy – rather than of modesty – that for years has lain over this huge area of art, is finally being lifted.

Picasso: The Power of Eros runs until May 1 at the Museum of Fine Arts Bern.

Around 100 prints are being exhibited, from the years 1905-1971.

The curator is Therese Bhattacharya-Stettler

Pablo Picasso was born on October 25, 1881 in Málaga, Spain and died on April 8, 1973 in Mougins, France. The Spanish painter, printmaker and sculptor is considered one of the 20th century’s most important artists.

His voluminous body of work, which is made up of paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures, had a tremendous influence on modern art.

His work is distinguished by a plethora of artistic genres and ranges from classicism to abstract.

Among Picasso’s best-known pieces are the pre-Cubist painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) and his monumental Guernica (1937), an artistic expression of the horrors of the Spanish Civil War.

The dove he created in 1949 for a poster advertising the Paris Peace Conference is now recognised worldwide as a symbol of peace.

(Adapted from French by Isobel Leybold-Johnson)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.