Raiffeisen Square should change name over anti-Semitic concerns, say historians

A group of historians and the artist Pipilotti Rist say a city square in St Gallen in eastern Switzerland should be renamed. It is currently named after the German founder of the cooperative Raiffeisen banks, who held anti-Semitic views.

To Swiss ears, the name Raiffeisen conjures up images of fields, honest work and rural tradition. For years, the bank’s logo featured three ears of corn. Following the recent takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS, Raiffeisen is now Switzerland’s second largest banking group.

Even after the news hit that the former chief executive of Raiffeisen Switzerland, Pierin Vincenz, had paid for strip club outings on company expenses and was convicted for fraud and embezzlement, customer numbers continued to rise.

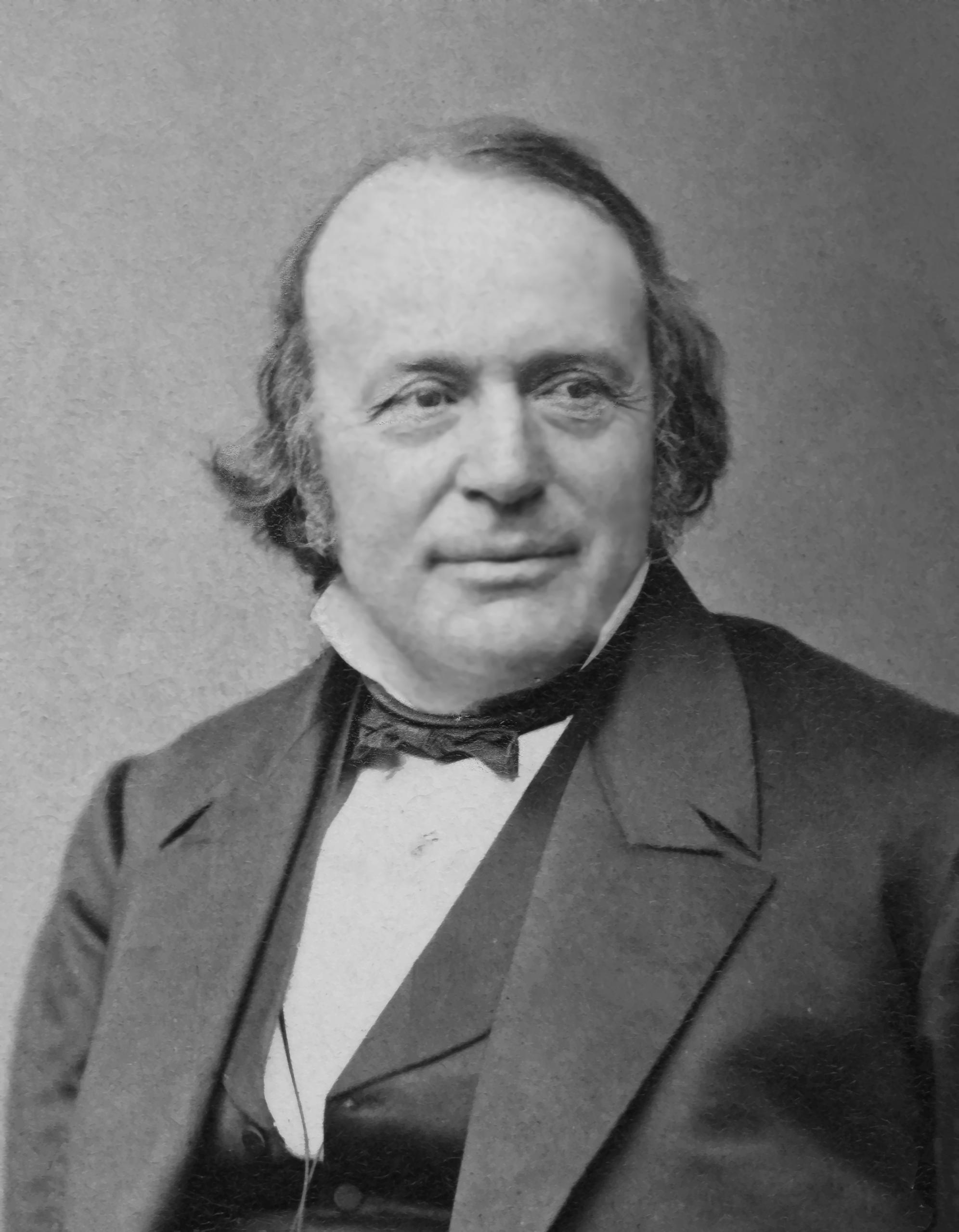

Yet the group’s seemingly indestructible name has now come under criticism. As laid bare in a biographyExternal link, the bank’s German founder, social reformer Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen, was not just a benefactor but also a staunch anti-Semite.

This is why a square with his name in the city of St Gallen should be renamed, to put an end to the “historical amnesia” surrounding Raiffeisen’s views. Such is the demand of a group of Swiss historians including Stefan Keller, politicians such as Paul Rechsteiner and exhibition organisers such as Hanno Loewy (director of the Jewish Museum Hohenems), as well as the artist Pipilotti Rist.

They say the square should instead be named after the orthodox Jewish woman Recha Sternbuch, who smuggled several Jewish refugees to St Gallen from 1938 and later organised the rescue transport of 1,200 Jews from the Theresienstadt concentration camp to Switzerland.

An anti-Semitic social reformer

The origins of the Raiffeisen banks lie, unusually for a financial institution, in the countryside. The cooperatives were set up in the 19th century to provide loans to impoverished farming families. They lent money for the purchase of buy seeds, which could be repaid later at moderate interest rates. The maxim was “all for one and one for all”, and general meetings were regularly held in the villages. This remained the case well into the 20th century.

Even today, the bank is not owned by shareholders but by members of the cooperative – who numbered two million in Switzerland in 2022. The country’s first agricultural cooperative bank opened in 1899 in Bichelsee, in canton Thurgau. Today, there are more than 800 Raiffeisen branches across the country; by comparison, UBS has just under 200.

When the scandal surrounding the group’s CEO Pierin Vinzenz became public in 2018, Swiss historian Hans Fässler held up the founder as a role model against which the bank should still measure itself today. He pasted a new sign over the one in St Gallen’s Raiffeisen Square, with the words: “Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen would turn in his grave if he knew what had been done with his bank.”

Fässler is still a Raiffeisen customer today and recently became a cooperative member. “I still find the basic idea of a cooperative bank, which moreover does not take on foreign commitments, convincing.” He would nonetheless like to change the sign completely today.

As a historian, he believes that the link is too close between the “cooperative idea of self-help and solidarity and the questionable intention of wresting financial activity in rural areas from the Jews, who were seen as dangerous and deceitful”. The founding years of the Swiss Raiffeisen banks should also be examined more closely in this light.

As early as the 1880s, the advocates of political anti-Semitism praised the consumer and credit cooperatives as applied, “practical anti-Semitism”, which was less bogged down in theory but directly attacked the supposed dominance of the Jews in financial transactions.

The Nazis also celebrated the bank’s founder as one of their own on the 50th anniversary of his death in 1938: “He was the first to combat Jewish usurious capitalism. He freed the German peasantry from the clutches of the Jewish usurers,” they exulted.

The book Raiffeisen: Anfang und EndeExternal link [Raiffeisen: beginning and end] published in 2018 by German sociologist Wilhelm Kaltenborn shows that this was not just a matter of appropriation. While Raiffeisen saw no reason to kill the Jews or deprive them of their fledgling civil rights, he supported the idea of deporting them to Palestine.

For he, too, believed that the Jews had been striving for dominance in Europe since the Middle Ages. He lauded the expulsion of the Jews from Spain at the end of the 15th century, for otherwise the gold from America would have fallen into their hands. In this way, he wrote, the emergence of Jewish control of world markets had at least been delayed. But he was convinced that the Jews controlled the press and the money and cattle markets and that they shunned physical labour.

A space for debate and interaction

A large part of the square named after Raiffeisen in St Gallen is taken up by a work of art by Pipilotti Rist. The spatial design, known as the City Lounge and built in 2005, “looks as if a section of the city had been covered with rubber granulate, of the kind found on sports grounds.”

It is intended as an urban meeting place, where people can exchange ideas and engage in democratic debate – which is one reason Rist is now also campaigning for the square to be renamed.

“I want to do my bit to make sure that, as a society, we nourish a culture of remembrance. For me, this means clearly saying: I don’t want a square I designed to be associated with an anti-Semite.”

In addition, the City Lounge adjoins a synagogue. It was built in 1881 – the year in which Raiffeisen theorised about the “Jewish question”.

Batja Guggenheim-Ami, former co-president of the St Gallen Jewish community, has also been calling for the square to be renamed since 2021, the 50th anniversary of Sternbuch’s death. However, the city still has not addressed her request.

“Renaming the square is a way of paying homage and showing gratitude to Recha Sternbuch for the Jewish community in St Gallen. Commemorating her will provide solace to those who suffered the unspeakable horrors of an inhuman ideology during the Holocaust,” says Guggenheim-Ami.

Recha Sternbuch was born in Poland in 1905, the daughter of an Orthodox rabbi. From 1929 she lived in St Gallen, where her husband Isaac Sternbuch, a citizen of Basel, ran a textile company. In 1938 Austria joined Nazi Germany and growing numbers of Jewish refugees started arriving at Switzerland’s eastern border. Recha Sternbuch now regularly smuggled refugees across the border in her car, and the Sternbuchs’ house became a temporary home for them.

In 1939 Recha Sternbuch was charged with smuggling and other similar offences. But this did not deter her. When the couple moved to Montreux, they set up an aid organisation that supported Jewish refugees worldwide.

As Guggenheim-Ami explains: “With untiring courage and fervour, she lived and acted according to these fundamental ethical attitudes throughout the Nazi regime, because, as Judaism says, ‘whoever saves one person, saves a whole world’.”

When approached, Raiffeisen bank responded that the renaming of the square was a matter for public and political discussion, and that the decision lay with the city council.

“However, as a place that bears the name of our brand, Raiffeisen Square is very important to us. We therefore hope and trust that the city council will base its examination of the request for renaming on a comprehensive analysis,” a bank spokesperson said.

Translated from German by Julia Bassam.

More

Anti-Semitism in Switzerland

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.