Author follows trail of Bruno Manser

Basel author Ruedi Suter slogged his way across leech-filled mud and other exhausting terrain trying to retrace the steps of the late Swiss rainforest activist Bruno Manser – whose disappearance and presumed death remain an enduring mystery.

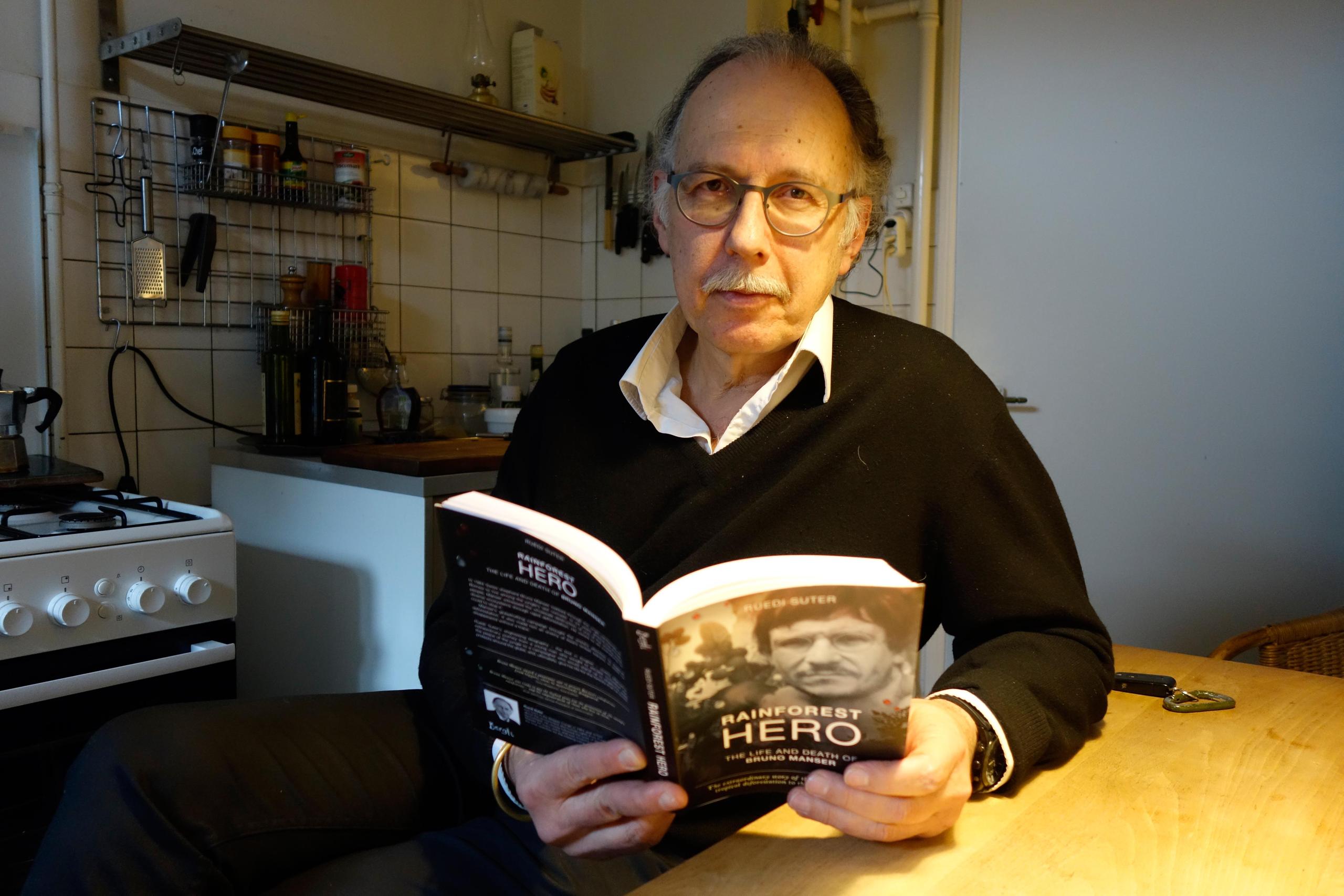

Though his forays into the Borneo jungle yielded few clues about the activist’s fate, Suter can’t be faulted for any lack of effort: Manser’s story lives on in painstaking detail in the book Rainforest Hero.

Glancing around Suter’s Basel home and office, it’s clear that the author is passionate about exploring other cultures and climate zones. Tribal African fabric enlivens the cushions; portraits of Native Americans gaze from the kitchen wall; and maps, books about rainforests and copies of National Geographic cover his two desks.

Suter writes primarily about the environment and human rights. His book on Manser, recently translated into English and published by Bergli BooksExternal link, covers the life of the man who left Switzerland to live among the Penan people in Sarawak.

Of the first time he met Manser, Suter wrote: “The first things I noticed were his alternative clothing and his composed manner. Then his chuckle, which exploded into a hearty laugh. And finally his ability to convey complex situations in simple words, making them lively and credible. Here was someone who could describe in graphic terms to cossetted Europeans unimaginable conditions in a tropical region afflicted by suffering and destruction.”

Manser was working as a shepherd in Graubünden when he decided to move to Sarawak in 1984. He won the trust of the Penan, adopted their simple lifestyle, and ended up staying for six years before returning to Switzerland – from where he launched a tireless battle against the logging industry and its destruction of the jungle.

“Bruno Manser, a few months previously a naked forest ranger, now has to move in an environment of parliamentary buildings, auditoria and thickly carpeted reception halls,” continued Suter in the book, admiring Manser’s grace and ability to remain true to himself.

Always himself

“He was absolutely honest and direct. He had no prejudices, regardless of whether you were a cabinet minister or a hunter-gatherer. He was himself and always spoke as such – he didn’t adapt according to the situation. That was great,” Suter told swissinfo.ch. Suter first wrote about Manser for the Basler Zeitung, a daily newspaper. He covered Manser’s activities until his disappearance in 2000, and over time, the men became friends.

The 300-page book includes many first-person observations by Suter, and opens with his account of plunging into the jungle to search for traces of his friend – in the company of Manser’s brother and a few Penan guides.

“The Penan are wonderful people – extraordinarily peaceful and helpful. There are peoples with whom you feel alone if there’s a problem, but not with the Penan. I knew that if anything happened, they’d help me. Bruno experienced that as well,” said Suter.

Back in Switzerland, Suter interviewed many among Manser’s circles, including schoolteachers, colleagues, ex-girlfriends, and family members.

“He always wanted to be simply dressed,” recalled Manser’s mother in the book. “He never wanted to throw anything out and during his schooldays I had to darn many more things for him than for any of the other children. Sometimes I almost despaired.”

The voice of Manser is quite present as well, with numerous quotes from his writings and speeches – some of them very intimate.

“Should I do without the man-woman thing and above all be a person? Reserve the strength required for sexual love between two individuals for brotherly love for many people?” wrote Manser, wondering whether his thoughts were “just an excuse for his reluctance to take on the responsibility of family life”.

The book also contains many photos of Manser with friends and relatives, plus some remarkably detailed and colourful wildlife illustrations from his diaries.

More

An interview with Bruno Manser (1990)

A fighter

Manser’s sense of adventure sometimes proved hazardous – like when he sampled unfamiliar jungle fruit and became ill. Over the years, Suter often worried about Manser’s propensity for risk-taking.

“I always warned Bruno if his plans were life-threatening. I was afraid for him. He listened and nodded, but then he just did exactly what he’d planned,” said Suter. As the Penan began losing habitat to the logging industry, Manser fought to help them defend the land that they’d been living on for generations.

The Malaysian government was highly displeased with Manser’s activism, and banned him from the country – though he returned in secret more than once. To draw attention to his cause, Manser resorted to some extreme measures, such as a two-month hunger strike in front of the Swiss parliament and parachuting from a plane with a goat in his arms.

As for what ultimately became of Manser, Suter has tried to think of every eventuality – noting that the jungle is a dangerous place for a solo traveller.

“Was he murdered? Did he have an accident? Or maybe he was kidnapped – and is sitting in jail somewhere, isolated. Maybe he decided to cover his tracks and disappear because everything had become too much. Perhaps he wanted to be a legend, which is what he’s become in the meantime,” mused Suter – his brown eyes earnest, his white moustache somewhat downturned.

He thinks the most likely scenario is that Manser was killed, either by Malaysian security forces or by loggers. But what he can’t imagine is Manser killing himself. “He wouldn’t have done that to his family, friends, or the Penan. He was too much of a fighter.”

Bruno Manser Fund

Today, the Basel-based Bruno Manser Fund (BMF)External link continues the work that Manser started on behalf of tropical forests. Its focus is on helping the Penan people in the Malaysian federal state of Sarawak. For example, BMF is trying to establish a Penan Peace Park so that local communities can retain their ancestral lands while remaining open to sustainable development.

Another project involves mapping out the rainforest to help locals demonstrate their claimed land-owning rights to live there.

“In order to file a land right claim, you have to prove that you live in the area. You need to have a border, so it’s good if can map everything out, including trees that are important for your culture, or graveyards, for example,” explains Johanna Michel, who does research and campaigning for BMF.

She says the problem is that the Malaysian government doesn’t recognise the Penan as landowners because they don’t have any titles – even though their people have lived there for centuries.

“But if you can prove that [your family] lived there…and you know the names of all the rivers and mountains in the area, you can probably win a land right case and prevent logging companies from entering,” Michel says.

She identifies palm oil plantations as a new threat to the rainforests: “These monocultures really are evil for biodiversity, rainforests, and the people who live there.”

In June, the Swiss cabinet rejected a motion to exclude palm oil from a trade deal with Malaysia – arguing that this would hinder the negotiations. The rejection came after 20,000 people signed a petition expressing their concern for the rainforest as well as for Swiss rapeseed farmers worried about competition from cheap imported palm oil.

How far would you go to protect the environment? Tell us in the comments section below.

Contact the author of this article on Twitter @SMisickaExternal link.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.