Rooting out corruption in the forests of Borneo

Corruption is the driving force behind the destruction of the Malaysian rainforests and the displacement of indigenous people, according to a Swiss book which tracks the “timber mafia” around the world – and to Zurich banks.

“Follow the money!” was the fictionalised advice given to journalists by Deep Throat, the informant who helped reveal the Watergate scandal. It is also the title of the first chapter of “Money LoggingExternal link: On the Trail of the Asian Timber Mafia” by historian and campaigner Lukas Straumann.

“I was looking for a title that made clear that it’s all about money – it’s not about destroying the environment,” Straumann, 45, told swissinfo.ch in Bern before setting off on a world book tour of cities where the illicit funds have allegedly been invested.

“The intention of the people who destroy the rainforest is to make money, and they’ve made huge amounts of it. We’ve calculated that over the past 25 years more than $50 billion (CHF47 billion) in gross revenue from logging has been obtained in Sarawak alone. The question is where that money is now, because the people are poor and the forest has gone.”

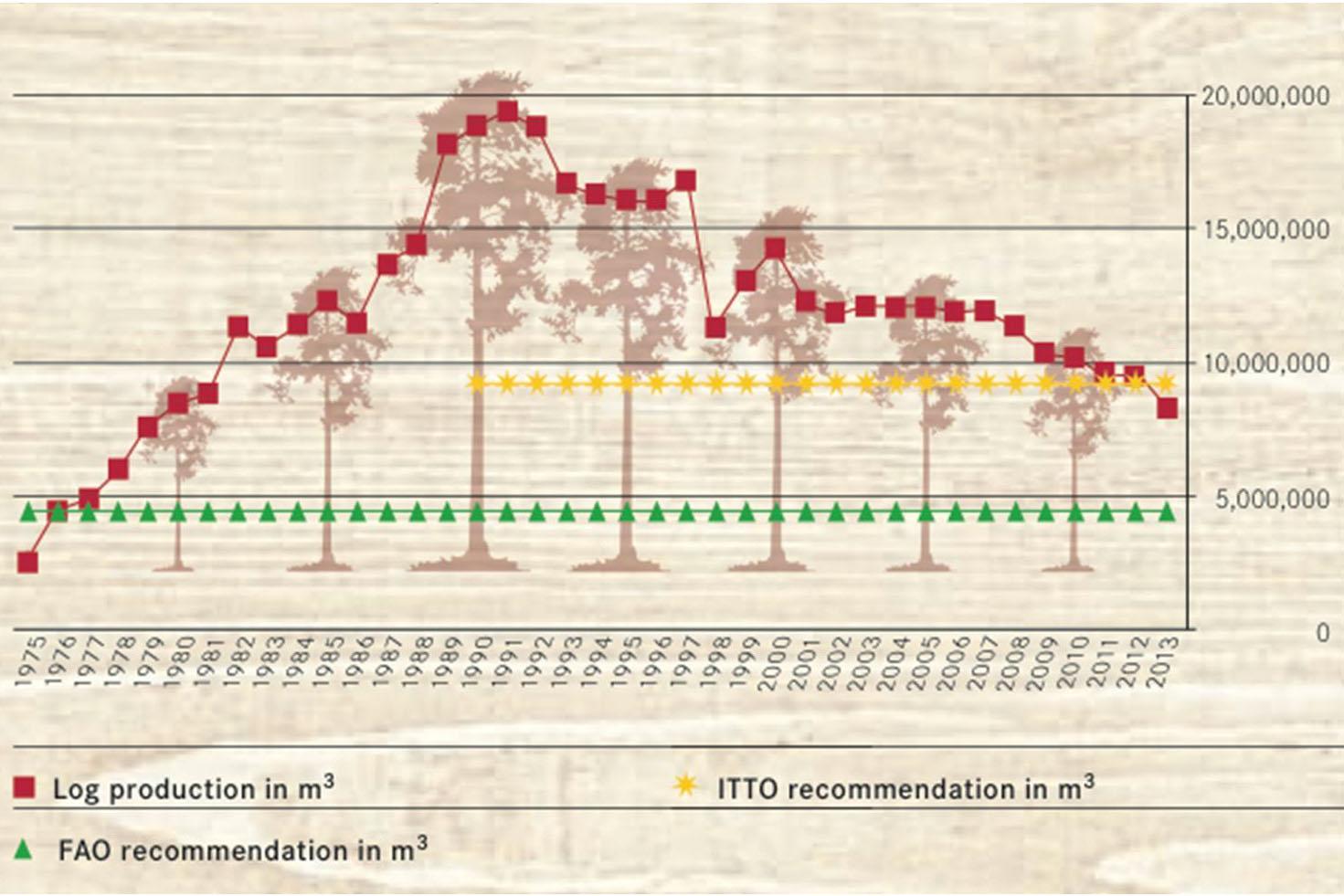

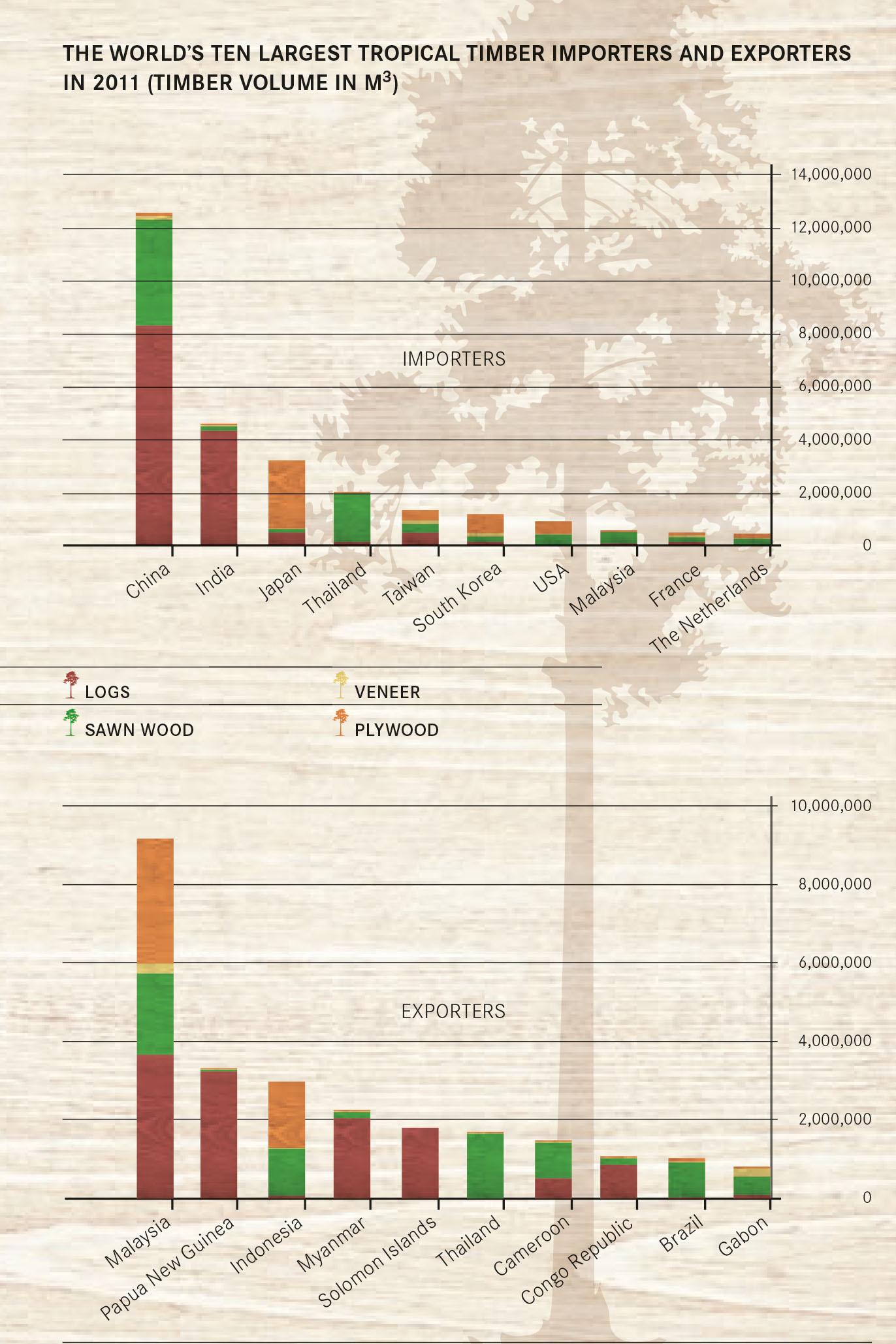

Sarawak, a Malaysian state in northern Borneo three times the size of Switzerland, has long been the world’s largest exporter of tropical timber but log production has fallen significantly in recent years. A 2012 reportExternal link by London-based NGO Global Witness said Sarawak had been left with only 5% of its once pristine tropical rainforests intact.

“In 2010, Sarawak accounted for 25% of the world’s exports of tropical logs, 15% of global tropical sawn wood exports, and almost half of all tropical plywood exports by source country exporters. All of this from a forest estate which represents just 0.5% of the global total,” the report said.

‘Mr Ten Per Cent’

Straumann is executive director of the Basel-based Bruno Manser Fund, which campaigns for Malaysia’s rainforests and their inhabitants, such as the Penan. In his book, published on Monday despite legal threats (see box), he firmly points the finger for the Penan’s plight at Abdul Taib Mahmud (known as Taib), the long-term chief minister and current governor of Sarawak.

Bruno Manser

Bruno Manser was born in 1954 in Basel. From 1984 to 1990, he lived in Sarawak with the Penan.

After returning to Switzerland, he founded the Bruno Manser Fund, a human rights and environmental organisation that champions the rights of Sarawak’s indigenous peoples.

Manser has been missing since his last trip to Borneo in May 2000 and was declared dead in 2005.

“The book is a wake-up call to the international community to treat the Taib family as what they are: politically connected criminals who have stolen vast assets from the people of Sarawak in a carefully planned effort,” he said. “He’s basically the Mr Ten Per Cent who collects from every contract in the country.”

Taib has always denied taking kickbacks or hiding assets abroad. He maintains deforestation is being done in the name of much needed development.

However, with the help of witnesses and whistle-blowers, Straumann explains how bribes are laundered and invested around the world in property and other assets.

Swiss banks have been the focus of previous complaints by the Bruno Manser Fund, with UBS and Credit Swiss both having lengthy entries in the index of Money Logging.

“One of the stories in the book is the case of UBS and the chief minister of Sabah, a state in northern Borneo. We were given two folders of documents showing that over $90 million of corruption proceeds had been laundered through UBS banks accounts in Hong Kong and Singapore.”

As a result of this case, the Swiss prosecutor’s office confirmed in August 2012 it had opened a criminal investigation into the allegations. For its part, UBS told swissinfo.ch at the time that “the anti-money-laundering policies applied by UBS are among the strictest worldwide. If assets linked to criminal activity were discovered to have been deposited with UBS, then UBS would be obliged to notify the money-laundering authorities”.

Restitution

Straumann says that at an international level it is important for governments of countries where the Taib family has brought its illicit assets to freeze these assets and later hand them back to Sarawak.

“The problem is that Switzerland, for example, has a long history of restitution, but the Swiss government only freezes assets once a government has fallen, for instance when [former president of Egypt] Mubarak fell, 15 minutes later the foreign minister announced they had frozen his assets,” he said.

“Of course they knew all the time that the money was there, but no one would touch it as long as these people were in power. That’s one of the key problems we’re facing: as long as Taib is still governor and the current Malaysian government depends on the votes from Sarawak to stay in power, it’s very hard to get their co-operation to do something about this situation.”

So how does Straumann rate the Swiss government’s efforts in standing up for the rainforests and the Penan and putting pressure on the Malaysian government?

“I think there’s a lot of goodwill from the Swiss government. Bruno Manser raised awareness of the problem and Switzerland has an active role in the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO). However, the ITTO in itself is a failure because it has really failed to bring tropical forestry to sustainability,” he said.

“As of today, less than 10% of tropical forests are managed in a sustainable way and the ITTO has become a very weak organisation. It has known about the situation in Sarawak since the early 1990s and never complained or spoke out against it.”

‘Patently untrue’

Contacted by swissinfo.ch, the ITTO said these accusations were “patently untrue and unfair”, saying the 10% figure (which it didn’t dispute) had grown from less than 1% in the early 1990s and from under 7% in 2005.

Emmanuel Ze Meka, the organisation’s executive director, argued that despite not having much funding, it had managed to help “almost all countries” develop appropriate laws and demarcate permanent forest estates.

“We have a strong programme to combat illegal logging and other illegal forest activities, spearheaded by our cooperation with the EU FLEGT programmeExternal link,” he said.

Ze Meka pointed to a list of ITTO projectsExternal link in Malaysia that include support for forest dwellers. “The ITTO has supported substantial work on community forest management and buffer zone management around protected areas in Malaysia, most of it in Sarawak,” he said.

“While we have no projects or programmes dealing with corruption at a general level in any of our member countries, our work to bring transparency to the tropical timber sector by publishing detailed timber trade statistics and prices serves as a general brake on corruption in the timber sector.”

Ambition

Despite being unimpressed with the ITTO, Straumann remains “relatively optimistic”.

“There are things we can’t change and we have to be very clear about that. On the other hand, if things do change, it will have to start in Malaysia itself. I think there is a growing middle class that is aware of the situation. For example we had a phone call yesterday and someone ordered 5,000 copies of the book to be distributed in Malaysia!”

The final chapter of Money Logging is called “Rainforests without Corruption”. Is this possible?

“Maybe it’s like Italy without the Mafia – it’s a dream! But we should have this ambition. If we don’t fight corruption, we can’t save the rainforests. We should put pressure on the financial sector to do their homework and stop pretending they are doing things which they are not,” he said.

“And ultimately I would like to see Taib in jail not a governor’s palace.”

Legal threats

“Money Logging: On the Trail of the Asian Timber Mafia” by Lukas Straumann was published by Basel-based Bergli Books on November 3, the opening date of the 50th session of the International Tropical Timber Council in Yokohama in Japan. The original German edition came out in February.

Straumann told swissinfo.ch: “The German book raised awareness with German-speaking officials and corporate decision-makers but we expect the big splash from the English version.”

Taib instructed his London lawyer, Mishcon de Reya, to stop the international launch of the English edition. In a letter sent to Bergli Books, they wrote: “If the book is published in English by a reputable publisher, it will cause colossal and irreversible harm to our client’s reputation.”

According to Mishcon de Reya, the book is based on an “entirely false and highly damaging premise”. It “accuses our client of being a ‘despot’; having committed crimes; earning billions of dollars illegally from the timber trade; hiding that fortune abroad through sham companies; committing ‘one of the greatest environmental crimes in history’; being a ‘corrupt autocrat’; breaching international laws and regulations; using his profit from logging to feed corruption; and finally, having ‘liquidated a forest in order to keep himself at the helm of a state’”.

In a similar letter to Amazon UK on October 23, the lawyers demanded the online retailer do not distribute the book.

Straumann refutes Mishcon de Reya’s demands and stated that he would not retract a single word as the book has been meticulously researched and is strictly fact-based. Bergli Books has assured the Bruno Manser Fund that the book will be on the market as agreed. Amazon has not reacted to the letter and is still offering the book for sale.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.