September launch for “Big Bang” machine

The countdown has begun for the launch of the world's most powerful particle accelerator, aimed at throwing light on the origins of the universe.

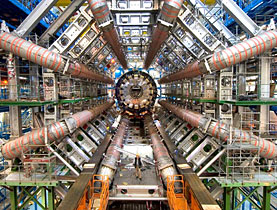

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC), housed in a circular tunnel under the Swiss-French border near Geneva, will recreate conditions just after the so-called Big Bang, which many scientists believe gave birth to the universe.

The first attempt to circulate a beam in the SFr6 billion ($5.95 billion) machine will be made on September 10, the European Organization for Nuclear Research (Cern) said on Thursday.

Scientists from around the world have been keen to start running experiments on the LHC, three decades after its conception, half as long in construction, and several years behind schedule.

“We’re finishing a marathon with a sprint,” said project leader Lyn Evans. “It’s been a long haul, and we’re all eager to get the LHC research programme under way.”

The new Geneva collider will recreate the rapidly changing conditions in the universe a split second after the so-called Big Bang, the theory that the universe expanded from an extremely dense and hot state some 13.7 billion years ago and continues to expand today.

Scientists hope the experiment will help explain fundamental questions such as how particles acquire mass. They will also probe mysterious dark matter – the invisible mass of energy that is believed to form 96 per cent of the universe – and investigate why there is more matter than antimatter.

Whizzing protons

The LHC will seek to collide two beams of particles at close to the speed of light in the 27-kilometre-long tunnel 100 metres under the ground.

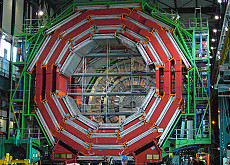

Beams of hydrogen protons will whizz around in opposite directions until, bent by powerful superconducting magnets, they will smash together in four bus-sized detector chambers, where they will be annihilated at temperatures hotter than the sun.

“Starting up such a machine is not as simple as flipping a switch,” the laboratory said in a statement.

The commissioning starts with the cooling down of each of the machine’s eight sectors, then electrical testing of the 1,600 superconducting magnets, after which each sector’s circuits, and then the sectors themselves, are powered together so the LHC can operate as a single machine.

The collider has massive detectors filling huge rooms at intervals along the tube. They will record the shower of particles that result from collisions so that they can be analysed by powerful computers.

The Cern laboratory will start stepping up the power with the hope of reaching a new threshold of energy by the end of this year. Further increases are planned until the equipment runs at full power, probably by 2010.

However, there are unlikely to be any immediate discoveries once the LHC is set in motion.

“We will accumulate data for two years and it will take a lot of time to interpret,” Cern’s director general Robert Aymar said back in May.

“Not risky”

Physicist Ulrich Straumann, who represents Switzerland on Cern’s executive board, is also eagerly looking forward to launch day.

“It’s part of the human condition to ask questions about where we come from,” he told the Swiss news agency, adding that the LHC’s high costs are fully justifiable.

And the experiments to be carried out are not irresponsibly risky, said Straumann, in reply to worries from German biochemist Otto Rössler.

According to the German scientist, the colliding particles could result in black holes that suck up the Earth.

“There are no such risks,” said Straumann, adding that Cern had seriously looked into these kinds of questions.

The money to construct the collider has come from the 20 Cern member states as well as observer countries like the United States, which alone has contributed US$531 million.

Much of the interest in the project has come from the US since Congress in 1993 halted construction of a machine that would have been even bigger – the proposed Superconducting Super Collider in Texas.

Of the 9,000 scientists planning to work with the LHC, the largest group – 1,260 – is from the US.

swissinfo with agencies

Cern was founded in 1954 by 12 states, including Switzerland, and now has 20 member states.

The LHC tunnel is 27 km long and runs between Lake Geneva and the Jura mountain range. When it was excavated, its two ends met up within 1 cm.

Cables for the LHC contain 6,300 “superconducting filaments of niobium-titanium” that are 0.006 mm thick. In total, they stretch more than 10 times the Earth’s distance to the sun.

The LHC contains the world’s largest fridge. Its temperature is colder than deep space.

The LHC’s two proton beams will use as much energy as a 400-metric ton train travelling at 200 km/h.

The system’s magnet contains more iron than the Eiffel Tower.

Data recorded by the LRC will be enough to fill 100,000 DVDs each year.

Heads of state will attend the LHC’s official inauguration on October 21.

In the LHC, high-energy protons in two counter-rotating beams will be smashed together to search for exotic particles.

The beams contain billions of protons. Travelling just under the speed of light, they are guided by thousands of superconducting magnets.

The beams usually move through two vacuum pipes, but at four points they collide in the hearts of the main experiments, known by their acronyms: ALICE, ATLAS, CMS, and LHCb.

The detectors could see up to 600 million collision events per second, with the experiments scouring the data for signs of extremely rare events such as the creation of the so-called God particle, the yet-to-be-discovered Higgs boson.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.