Silent Night in the trenches and barracks

December 25, 1914 was the first Christmas of the First World War. Morale was low among the Swiss soldiers who were guarding the country’s borders. They yearned for peace and, especially, for the love of their families.

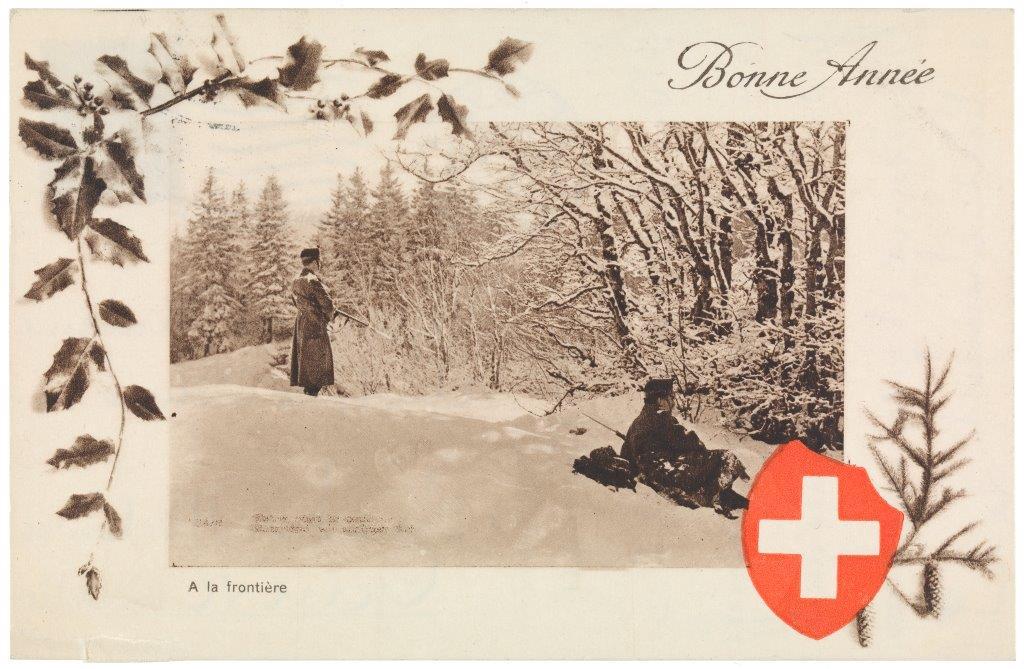

The European powers were at war. Switzerland remained neutral but there were fears that foreign troops would invade and use Switzerland as a passageway to other countries. Fortifications and roads needed to be built, the frontiers to Germany, Austria, France and Italy patrolled.

“At the outbreak of war in August 1914, several thousand soldiers were mobilised, and their horses. It wasn’t really a well-organised operation, the authorities had been caught a bit unawares,” said Dominik Wunderlin, curator of the Sad Christmas exhibitionExternal link, running at the Basel Museum of CulturesExternal link until January 11, 2015.

“This very quickly affected the morale of the Swiss soldiers, especially as the seasons turned towards winter,” he added.

People often had to live in very basic accommodation, and indeed there are stories of how soldiers, arriving in the villages in the Jura, which bordered the German-run region of Alsace, often had to remove muck and pests before they could bunk down.

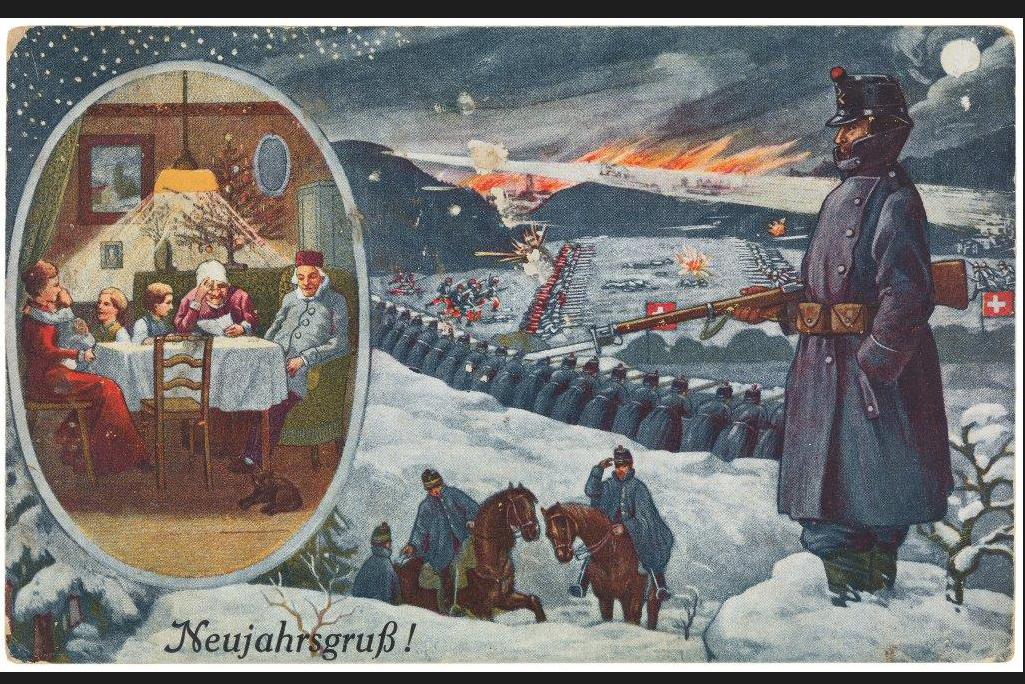

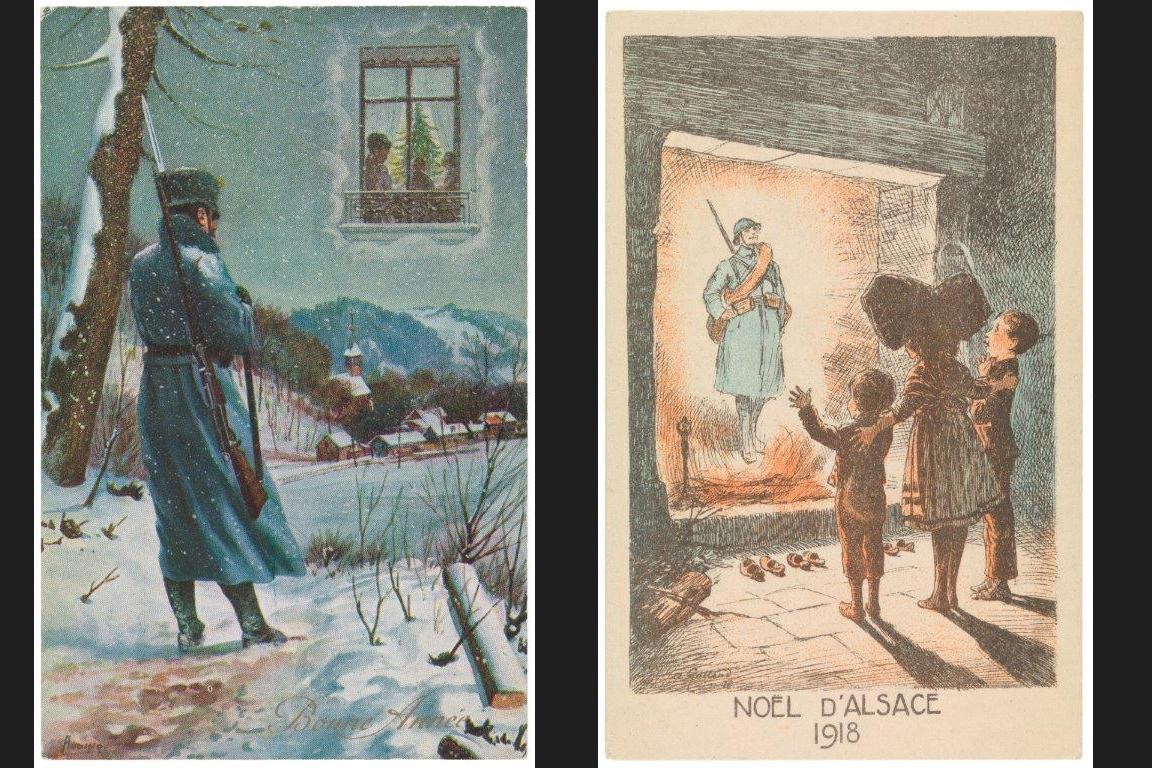

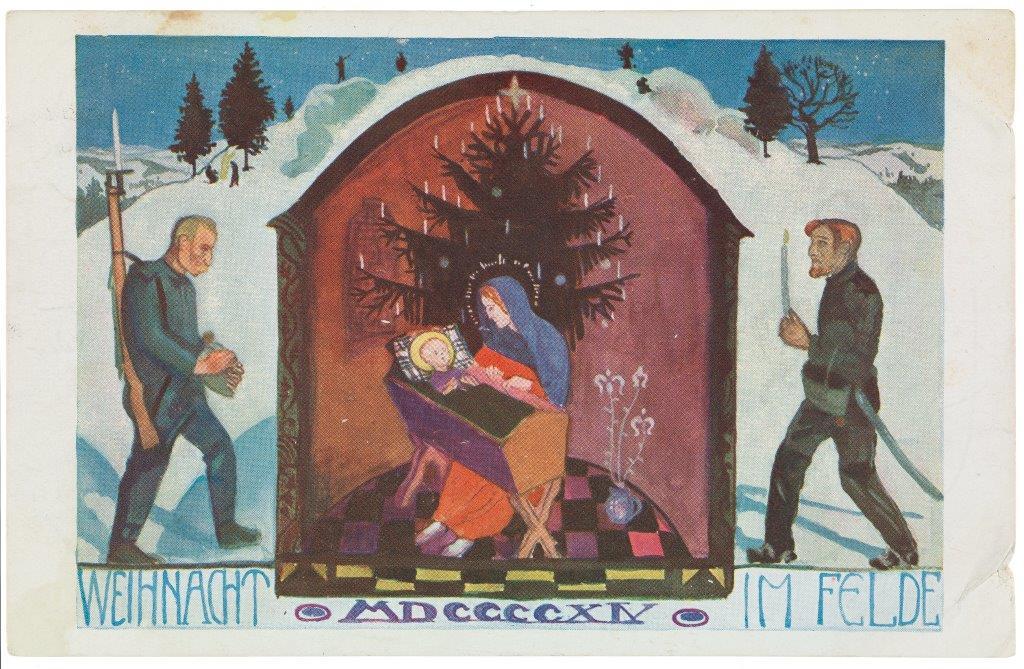

Relief was found in writing picture postcards home, which were specially produced. A typical example on display at the exhibition, which focuses primarily on the First World War in Switzerland and its neighbours, show a brave soldier on duty, staring off into the distance. Encircled in the clouds is his family, Christmas tree in the background, thinking of him.

Wartime “texts”

“The First World War postcard was the text message of these times,” Wunderlin told swissinfo.ch. “You couldn’t write much on them as there wasn’t much space. Often people wrote ‘a letter is on its way’. It was meant to be a sign of life.”

“There are also postcards showing how soldiers celebrated Christmas, sometimes in posed scenes, especially on the photo cards.”

Thus the “Christmas in the army camp” picture postcard (see gallery) shows soldiers inside their camp, enjoying a festive meal, courtesy of the Swiss army. A group of men admire the lit Christmas tree, one of them raising his glass in a toast.

This morale-boosting practice of marking Christmas continued during the Second World War, when soldiers were again on duty at the Swiss borders. Archive Swiss television footage on show at the exhibition – First World War footage is rare – nicely illustrates what it was like to celebrate the Yuletide away from home in wartime.

More

Swiss soldiers celebrate Christmas

Peace and quiet could also be found in the “Soldiers’ Taverns”, which were founded in autumn 1914 by the formidable Else Züblin-SpillerExternal link, journalist and advocate of the temperance movement. These cafes offered a cheap source of healthy food as well as games, books and writing paper. Alcohol, a problem among the ranks, was banned. There were 1,000 of these taverns by the end of the war.

Of course, the Swiss soldier’s life was a world away from his British, French and German counterparts, who, in part, spent Christmas in the trenches, listening, as one letter from the Belgian Front quoted in the exhibition says, “to the cries of the wounded, the whistling of the bullets and the exploding of grenades – a terrible Christmas music”.

Tri-national Christmas truce

Sometimes, however, soldiers took the Yuletide initiative themselves. The Christmas Truce of 1914,External link in which German and British soldiers climbed out of their trenches, sung carols like “Silent Night” and played football on No Man’s Land, is well known.

Perhaps less famous is the get together of Swiss, German and French soldiers on Christmas Eve 1916. This took place at Largzipfel, an outpost of the Swiss border in the Jura, where soldiers were stationed so close that they could hear each other coughing on the other side of the barbed wire.

The table was laid with “special foods” and decked out with candles, according to an account of the event.

“There were between 20 and 30 men, who managed to do what the politicians in their countries only managed to do several years later, that is, sit peacefully around a table,” it continues.

However, their military superiors were less than pleased by the party. The German and French soldiers were posted elsewhere shortly afterwards, because, as Wunderlin puts it, “if you have looked someone in the eye, you won’t be able to shoot them”.

The home front

Back at home, the soldiers’ families were also doing the best they could under the circumstances. Gift boxes of goodies and laundry were sent to loved ones.

But as the war continued, people had less to send. By 1915 rationing had been introduced in Germany, becoming particularly severe a year later. Switzerland suffered shortages too, such as for meat, from March 1917.

Away from the borders, civilians were nevertheless determined to celebrate Christmas. Preserved fruit and vegetables were brought out. Houses were decorated, sometimes even on a war theme, as the Zeppelin baubles on a German fake Christmas tree on display at the exhibition attest.

War also made its way into children’s toy boxes. For example, the German-made Eureka children’s pistols and guns also appeared in Swiss toy catalogues during Christmas 1914.

Some things don’t change, says Wunderlin. “If you go into any toy shop today you still see things which could be considered violent or war games, even if they are called other things,” he pointed out.

There are many moving aspects to the exhibition, from the poignant letter from a French soldier yearning for the “happy pre-war Christmases” instead of the “sad Christmas” from his invalid bed, to the home-knitted socks and small trinkets sent by families to their loved ones guarding the Swiss borders.

People showed fortitude and inventiveness, said Wunderlin. “But what particularly comes out is how people reached out for warmth and human contact, so important in this time of crisis,” he said.

Field post

The military mail service was a great boost to morale, delivering not only postcards and letters, but also packets of washing and boxes of goodies. Between 1914-1918 there were more than 192 million deliveries in Switzerland via field post. In comparison: the German service recorded 28.7 billion deliveries of all kinds during the same time. All were subject to censorship.

(Source: Sad Christmas)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.