Stiff competition draws filmmakers to cyberspace

Cheap technology means more films are being made than ever before, making acceptance to festivals like Locarno a long shot and a cinema run practically a pipe dream. But, at the same time, online pastures are growing greener for filmmakers after an audience.

“People think watching a film in the cinema is not necessarily the holy grail anymore, which I think is a little bit sad and a little bit great at the same time,” says Australian filmmaker Justin Olstein as the crowd filters out of the screening of his short film Fun City at the Locarno Film Festival.

The film is a poignant, neatly crafted 12-minute package about a day in the life of a man who oversees a fun fair and can’t get ahold of his estranged young son to wish him a happy birthday.

Over the course of his young career, Olstein has noticed a quiet but significant shift from a focus on the all-important festival circuit to a recognition that there are audiences to be had in cyberspace.

Festivals are “great for short films” and Locarno in particular is a good networking space for filmmakers because of its “big but small” atmosphere, he says.

But, he sometimes gets frustrated by different rules for different festivals that limit the reach of his films – Locarno, for example, only allows international premier film entries, meaning he couldn’t release Fun City online beforehand or attend other festivals that also required it to be a premier. That’s led him and other colleagues to adopt a “two-year festival strategy” wherein they submit to festivals for a couple years and then think about turning to other channels.

“For a feature film, you used to have to have a theatrical distributor attached before you could get money, and they’re just starting to ease up on that a little bit,” Olstein notes. “The walls are coming down, but very slowly.”

“On filmmakers’ bios, I’m starting to see, ‘it won an award at Cannes, at Sundance, and it has a million hits on [the online streaming service] Vimeo,’” he adds. “That’s now a legitimate thing to include because those are viewers – a million people have viewed your film online, who cares if it’s not at a festival?”

The Locarno Film Festival’s Industry Days offering has been lauded as one of the best efforts of its kind to bring filmmakers and distributors to the table and solve what industry office head Nadia Dresti calls “the biggest problem in the film industry: the gap between production and distribution”.

Now in its second year, the Step In initiative brings international sales agents, distributors, exhibitors and funders together in small working groups to discuss current challenges in the market and how to overcome them.

The third annual Carte Blanche event, this year dedicated to productions from Chile, shows seven films in post-production and awards one candidate the funds to finish the film.

And, the Open Doors Initiative focuses on geographical regions “where independent filmmaking is particularly vulnerable” to help filmmakers find support for their projects by offering training and potential co-production partners.

Too many films

That doesn’t mean festivals aren’t getting submissions – they are, and a ton of them.

“There are so many films around, we don’t know what to do with them,” Nadia Dresti, artistic direction delegate and head of the industry office at the Locarno Film Festival, tells swissinfo.ch. “This year, we could have screened 2,000 films [based on the submissions we got] – this is crazy.”

Out of those 2000 submissions, the festival ended up screening about 250 and selecting 100 for possible prizes, of which “not all reach the cinema”, she notes.

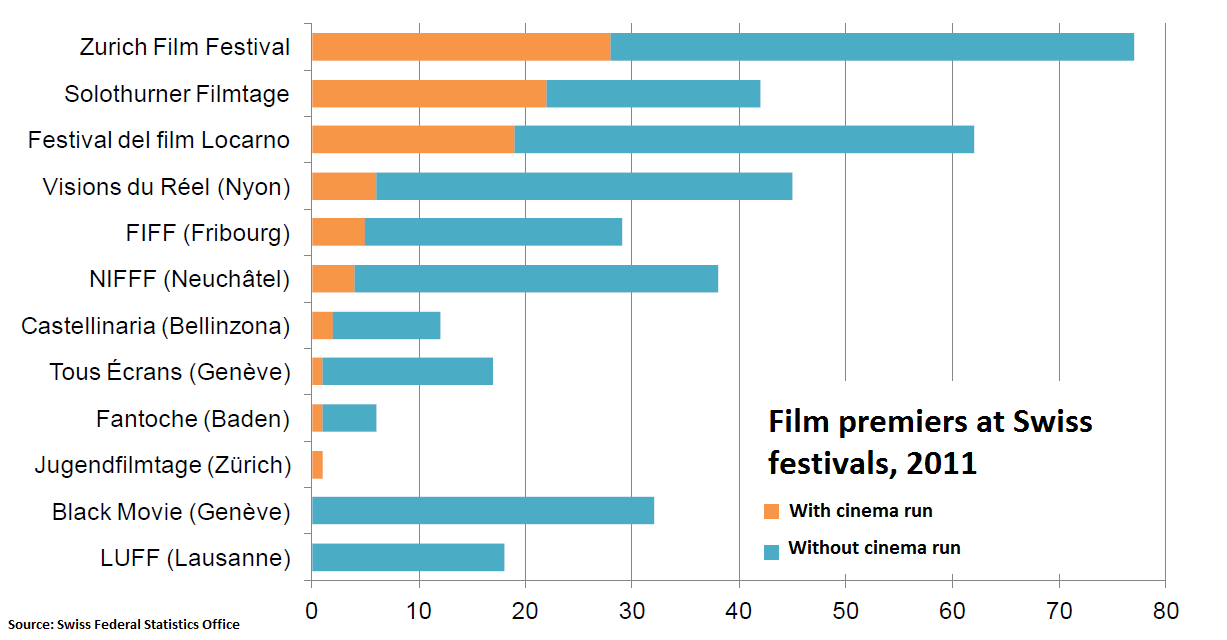

A study by the Federal Statistics Office released during this year’s Locarno Film Festival bears that out – more than a quarter of the feature films screened in Switzerland in 2011 (the last full year of data available) and nearly half of the documentaries were only shown at festivals and never in cinemas.

Out of the ‘feedback loop’

Figuring out what to do with the quality films that never see a cinematic release was 27-year-old K.C. McLeod’s mission in creating his United States-based startup film streaming company, Vyer Films.

“My parents were always calling me saying, it’s Friday night, we’re getting ready to sit down and watch a movie, what should we watch?” he tells swissinfo.ch. “There seemed to be a solid connection between the films that were out there being made by credible filmmakers who didn’t have the professional resources to distribute them and these audiences who were looking for these exact kind of films.”

The Vyer Films team winnows down thousands of film possibilities that had festival runs but didn’t get picked up by distributors. Then, users get targeted selections delivered to their inboxes twice a month that they can either stream online or download.

McLeod says Vyer Films keeps its distance from current festivals, choosing instead to focus on films that had a festival run a few seasons ago but didn’t make it to the big screen, often because of being overshadowed by big names at the time.

“There is a nice quality to keeping our distance from festivals in the immediate sense because our goal is to find the films no one’s paying attention to that deserve to be seen,” he says. “At festivals, there’s this feedback loop of what’s good and what should be seen – there’s this buying frenzy and then the films come out a few months later and some of them really just don’t go anywhere.”

The online streaming and download marketplace for independent film is becoming more and more crowded, with various subscription services catering to mobile audiences. It is well-established in the United States and is slowly making inroads in other parts of the world.

Netflix, the American market leader in streaming video, is also available in Canada, Latin America, Britain and Ireland, with plans for further international expansion.

YouTube has launched a pilot offering of streaming content subscription channels that cost, on average, $2.99 per month.

Vimeo, long a champion of independent filmmakers, launched “Vimeo On Demand” in the United States in March, allowing subscribers to stream full-length films for a fee. It offers filmmakers who share their work on the service a 90/10 revenue split.

Apple pioneered the oft-used 70/30 revenue split for downloads on its iTunes service, with 70 per cent of the revenue going to the filmmaker.

The price is right

At $20 (CHF18) per download and $10 per month for a streaming subscription, the service isn’t as cheap or as prolific as some others out there – but that’s not the audience McLeod is after. He insists he wants quality over quantity, and the company shares the profits with filmmakers.

“I think indie filmmakers have understood now that there is no big payday coming from major streaming services,” he says. “I think they’ve come to realize that we can price ourselves differently than mainstream films because, at the end of the day, if it’s really important to you to see it tonight, you’ll pay the 20 dollars [for a download].”

Filmmaker Olstein, however, doesn’t believe audiences are quite ready to fully embrace online-only releases without the “clout” brought by a run at the cinema. But, he finds subscription-based streaming services an attractive option, especially given that his native Australia leads the world in illegal downloads of films and TV shows and that not many paid online services are available yet to give people an alternative.

“The audiences just aren’t coming to the films in the cinemas,” he says. “It’s not to say they don’t want to watch them – they just want to watch them when they want, maybe turn it off halfway through and watch the rest later on. If you can tap into an audience and find out exactly the kind of film they are after, they’ll find it and they’ll hopefully pay money to go and see it [in some form].”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.