Striking a top note in a man’s jazz world

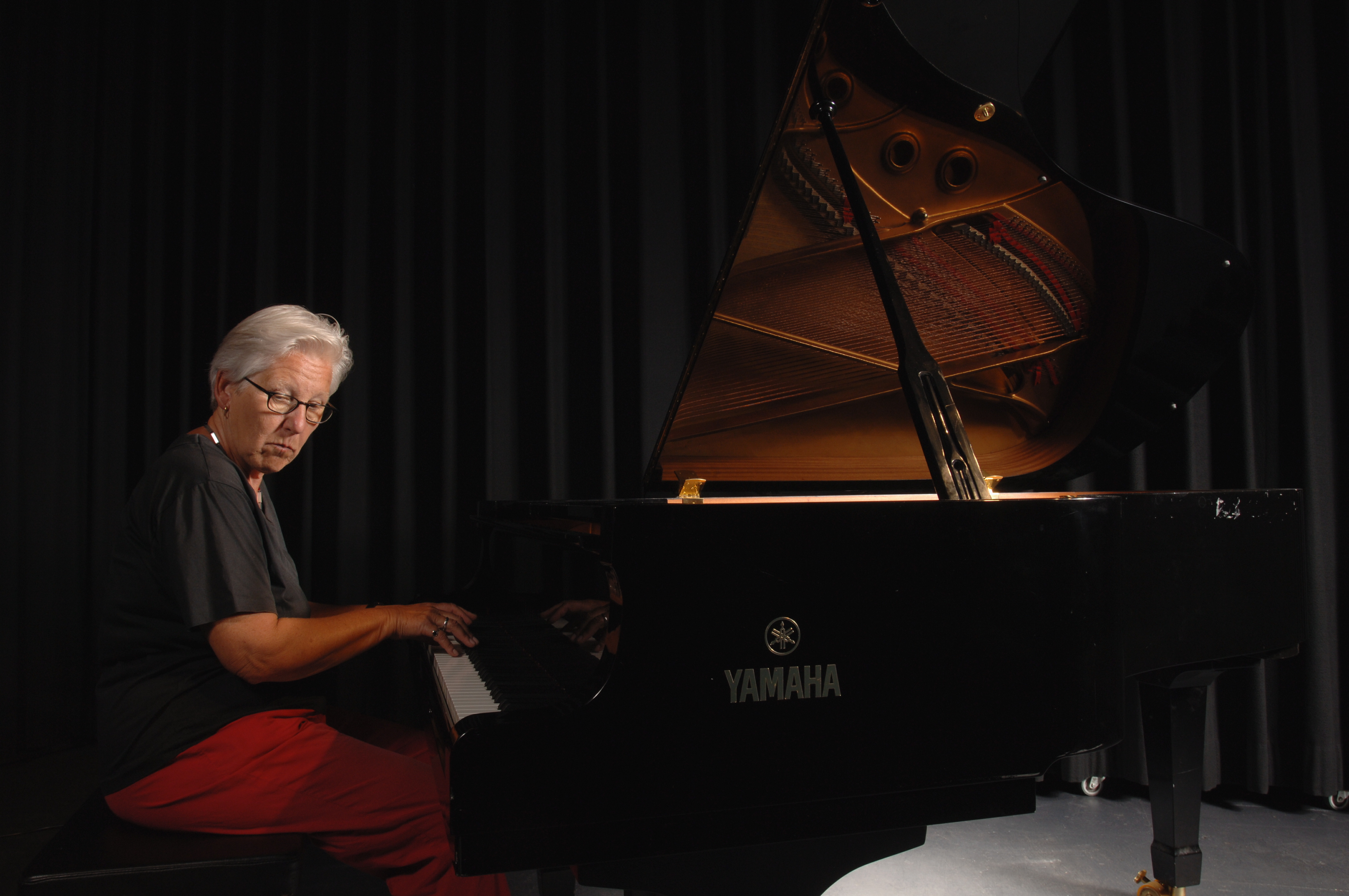

Jazz pianist Irène Schweizer, who turned 70 on June 2, is no stranger to breaking conventions – both musically and as a woman in a largely male preserve.

The grand dame of Swiss jazz and improviser extraordinaire is a pioneer of free music, which turns conventional jazz on its head. She has also been involved in the fights for women’s rights and against Apartheid.

This birthday year has been a busy one for Schweizer, a neat, grey-haired lady with a twinkle in her eye.

A highlight was the birthday concert in April at the prestigious Tonhalle hall in Zurich, normally the preserve of classical music.

“I was quite honoured to have been asked to play at the Tonhalle, which is of course not my scene, I’m more used to playing in smaller places such as festivals, jazz clubs and little theatres. But the Tonhalle is something else, it is acoustically the best you can get,” Schweizer told swissinfo.ch shortly afterwards.

“Usually the people are quite stiff, so I was a little bit worried it would not be a good atmosphere, but all my friends and fans came so it was great. I walked into the hall and without having played one note, I already had a standing ovation.”

This reception is a testament to Schweizer’s standing in the Swiss – and international – jazz scene. But it was not always thus.

All that jazz

Schweizer was born in 1941 in the town of Schaffhausen to restaurateurs. And it was in a room above the restaurant used by dance bands for rehearsals that the 12-year-old Irène got her first taste of jazz.

“I had been playing Swiss folk music on the accordion since the age of eight but when I heard jazz for the first time it was like… crash bang. I was blown away by this music and from then on I wanted to play jazz,” she said.

“Without jazz I wouldn’t be a musician.”

In 1960 Schweizer, entirely self-taught on the piano, entered the Amateur Jazz Festival in Zurich, winning first prize with her trio.

Schweizer’s victory caused quite a stir: “Jazz goes feminine” was one typical headline of the time. And it was unexpected: the main prizes included a packet of cigarettes and men’s shirts.

Café Africana

After a stint in Bournemouth and London learning English, Schweizer moved to Zurich, working by day as a secretary. By night she was to be found listening to exiled South African jazz musicians playing in the city’s legendary Café Africana.

“I studied American jazz. Of course I also had all the records of the time: Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk, but South African jazz was different, it was happier, more joyous. It was a different kind of music, but it got to me right away, into my heart.”

It was to be her biggest influence. She also became involved in the fight against Apartheid, playing at rallies in Zurich. Schweizer still makes music with the drummer Louis Moholo.

“A lot of the musicians died very young, some of them in car accidents, others we never exactly learned why they died. It was really sad. I think they were homesick because they couldn’t go back to Jo’burg or Cape Town,” she said.

Breaking convention

The late 1960s brought another change: free jazz – or free music as it is now known. Driven by American musicians such as Ornette Coleman and Archie Shepp, it was all about breaking down the normal conventions of jazz like harmony and time keeping.

Schweizer became one of the key European pioneers of the art form. But not everybody liked the style at the beginning.

“The audience thought, ‘oh my god what kind of music is this now’? Because it was, of course, different, it was revolutionary and we fought against governments, against Apartheid and for black people in the United States who were very angry and protesting against laws,” she recalled.

Audiences also had to get used to a woman playing not just jazz but such radical music – Schweizer’s style could be furious and she was not above using her elbows on the keyboard.

“In Europe I was the only female musician playing jazz in free music,” Schweizer said. Usually women were to be found singing jazz – and far more conventionally. Schweizer was called upon to prove her worth.

Going with the flow

During the 1970s she became involved in the women’s liberation movement in Zurich and by the end of the decade had joined the Feminist Improvising Group, the first all-woman group of its kind, set up by Englishwomen Lindsay Cooper and Maggie Nicols.

Schweizer still plays with Nicols, a vocalist, in a group called Les Diaboliques, whose third member is classically-trained French bass player Joëlle Léandre.

The pianist said that nowadays, free music, which enjoys greater acceptance, attracts both classical and jazz musicians.

“When we play together it works because we don’t play tunes or rhythms, there’s nothing fixed, it’s always free.”

Schweizer has seen her plans to slow down thwarted this year by all the fuss over her birthday. “This year will be the busiest I’ve ever had,” she laughs.

She doesn’t enjoy the travelling that touring entails and would rather have a quieter life in Zurich.

“Music is still a joy. It’s great to be able to play, to have people who make music together and we’re listening to each other and having fun,” Schweizer said.

“And now people accept us and most of them like the music more and more no matter what we play. It’s really nice. Actually it couldn’t be better.”

Schweizer – Moholo, Irène Schweizer, Piano, Louis Moholo, Drums (duo). Intakt records

Les Diaboliques, Live at the Rhinefalls, Irène Schweizer, Piano, Maggie Nicols, Voice, Joëlle Léandre, Bass, Intakt records

Various collaborations with Rüdiger Carl (clarinet, accordion)

The Feminist Improvising Group (FIG) were a five- to eight-piece free improvising avant-garde jazz and avant-rock ensemble formed in London in 1977. They were the first women improvisers and challenged the mainly-male scene of the time.

They performed live in London and toured festivals in Europe. FIG was open to women of all backgrounds. English filmmaker Sally Potter, who played the saxophone and sang, was one of its members.

The group used a lot of humour. Some men complained that the women couldn’t play their instruments well enough and were too “irreverent”.

In 1983, under the helm of Schweizer, FIG evolved into the European Women’s Improvising Group (EWIG), bowing to pressure that their name was “too political”.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.