‘Suddenly, the Swiss border became very deep’

The Swiss border is not a line but a space with many faces. In the Swiss Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale, this space fans out into a collective portrait.

Sea spray splashes onto my face as I ride the vaporetto across the Venetian Lagoon. San Pietro, Sant’Elena, San Isepo, Sant’Ana… Venice’s city core covers more than 120 islands, not counting the surrounding islands and the sandbanks of the Lido. The number also depends on whether you include the rocks that become visible when the sea is at low ebb and disappear again as the tide rises. “Dry land” is not a clear-cut concept in Venice.

“Orae – Experiences on the Border”, the title of the exhibition in the Swiss Pavilion at the Architecture Biennale, meshes well with the Venetian city’s approximate surface area. The Latin word can be translated as border or edge. It also means shore, that ever-changing stretch between land and water where different living worlds meet. The project, which was selected by the Swiss cultural foundation Pro Helvetia, is about the Swiss border. This border is not by the sea, and nor is it a line, but a space with many faces.

A four-strong team from Geneva, comprising the filmmaker Fabrice Aragno, the architect Mounir Ayoub, the landscape architect Vanessa Lacaille and the sculptor Pierre Szczepski, studied the Swiss border for two years. They travelled around in a truck, which they first turned into a workshop and then into a forum. They photographed and filmed, but above all they spoke to people living in border areas. They brought 49 stories to Venice and condensed them into a collective portrait of a living Swiss border.

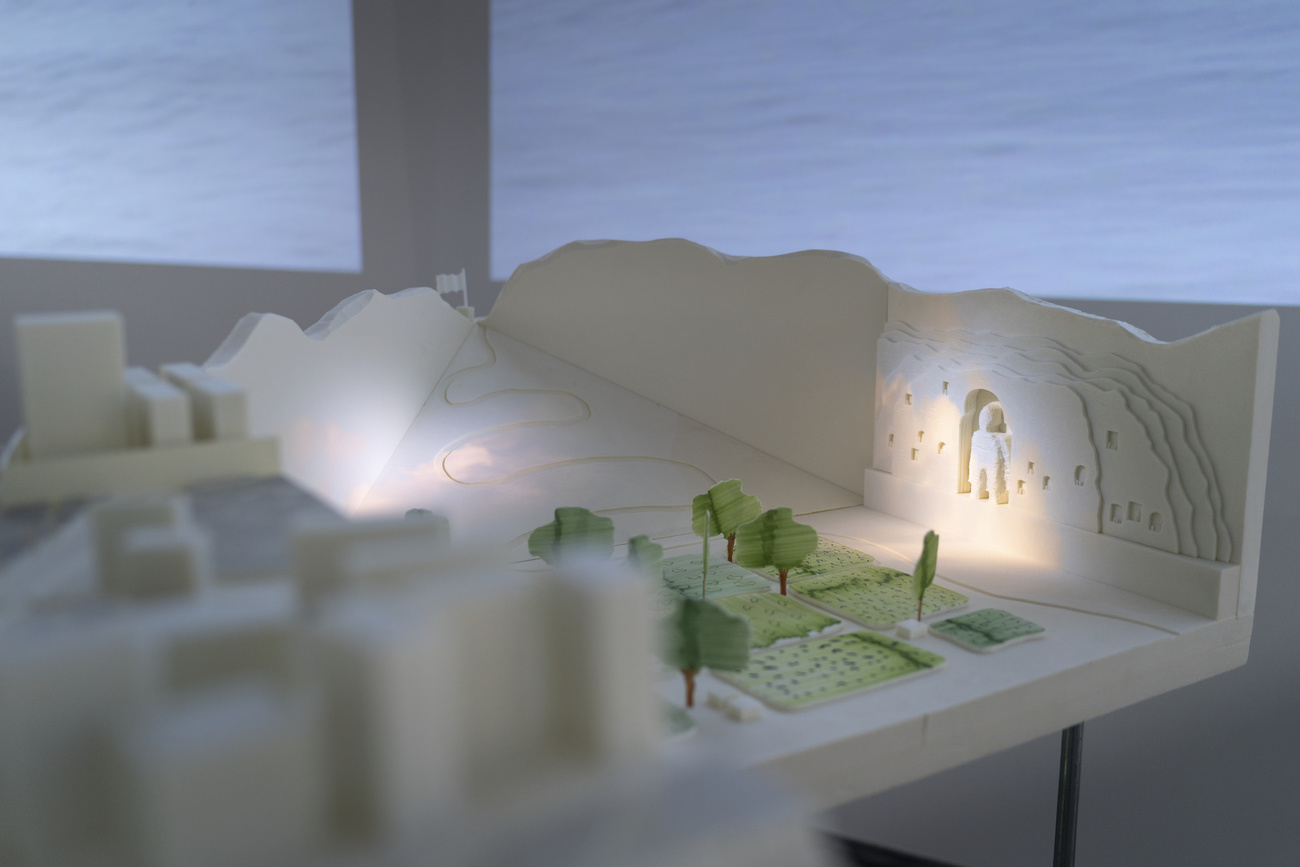

The team invited the residents of border areas to translate their individual perceptions into spatial models. These are imaginary, but nonetheless reveal realities. The model, as the architect’s most graphic tool, again proves its worth. As visitors to the pavilion, we can project ourselves into the models and take part in different people’s experiences.

Depending on who you are…

This already gives an idea of the political scope of the project. “Depending on who you are, perceptions and experiences of these realities vary greatly,” says Vanessa Lacaille, using the example of Ursula Fogliada-Salis from Castasegna in Switzerland and Delia Giorgetta from Chiavenna in Italy to illustrate how two people, both living in the Bregaglia valley, can have fundamentally different views of the same space. “For the woman from Castasegna, the border was something comfortable, like a paese (Italian for small village). She designed a very detailed model with the village and a chestnut grove. The other woman designed only a road to the Grand Hotel Maloja Palace where she works. A line crossing a pass; the landscape disappeared.”

Others, meanwhile, have no spatial conception of the border at all. An Afghan family, seeking asylum in Chiasso, said: “For us, borders are just barbed wire. We can’t make a model of that.” The mother, Massoma Amiri Yousefi, a lawyer who grew up in Afghanistan and worked in Iran, eventually built a model of the Bamiyan Valley – a place which became known to the wider world, at the very latest, with the destruction of the famous Buddha statues by the Taliban. The filmmaker Fabrice Aragno was particularly moved by this story. Not first and foremost because of the individual fates, but because it says something different about the Swiss border: “Suddenly, the Swiss border became very deep.”

Then there are those for whom borders are permeable. Marc Zehntner cycles through three countries to his work in Weil am Rhein, past the buildings of Novartis, Roche and the Vitra Museum. The border area here is a showcase of internationally celebrated architecture. Daniel Hahn, too, has to cross six customs posts if he wants to swim in the Rhine near Schaffhausen. For him, the frontier has a special character: “In the space between two customs posts, you never really know where you are. There is a feeling of permanent uncertainty.” Meanwhile, Annabelle Marlhes paces her daily commute with music, as she wends her way from Belley in France to her music school in Geneva. Each place she passes through corresponds to a specific song on her smartphone playlist.

The relationship between things

A staircase at the back of the exhibition area leads up to a small platform. Here we meet Jacqueline Kissling, who lives in Staad in eastern Switzerland. From her house she can see Lake Constance and the sky. “From here, I have a relationship with the world,” she tells us. “There’s the horizon, a segment of the planetary curve. The sky supplies us with all kinds of stories. The clouds all flow in from somewhere else. Perhaps that’s why the border doesn’t exist for me. The wind pushes those clouds at a higher elevation than those below. It’s spectacular in the evening at around 8:30, as the last plane flies overhead before landing at the airfield. It goes wooooh! (imitating the sound of an overhead plane). An illuminated cloud that emerges that way.”

Jacqueline Kissling’s aesthetic perspective is an invitation to let our gaze wander over the archipelago of models, images and voices. The superimposition of film images and models constantly creates new combinations. From the plane taking off over Lake Constance we get to the Geneva apartment of Gail Menzi, who has taken an undocumented child migrant into her care. The child also looks through the window at the aircraft, knowing he would not be able to board it. The open border area of Lake Constance is superimposed by the pejoratively termed bétaillère (cattle-wagon) boats on Lake Geneva, which ferry cross-border commuters to and from their work.

Switzerland as a border area

“We want visitors to develop their own perception of the border, their own narratives,” says Fabrice Aragno. And the exhibition catalogue says: “At the border, the relationship between things is more important than the things themselves.” Perhaps these statements also contain an answer to the question “How will we live together?” by Hashim Sarkis, curator of the Architecture Biennale 2021 – that we can learn from borders how to use this changing perspective in order to shape our own living space.

Switzerland, as a small country at the heart of Europe, with its many migrants and global network, has a different relationship to its borders than larger States. The French agronomist Matthieu Calame, who joined the team in organizing the project, goes as far as to describe Switzerland as an “immense border surrounded by Europe”. His border space, as depicted in “Orae”, breaks away from national borders.

As I move around the pavilion, I feel as if I’m back on the vaporetto. The 1,935 kilometre-long line, which draws the outline of Switzerland along the five neighboring countries, fans out into a living and vibrant space.

The Biennale “How will we live together?”, by Hashim Sarkis, can be visited until November 21, 2021: labiennale.orgExternal link.

The Architecture Biennale in Venice opened in May 2021. The Pavilion Days were held from 23 to 25 September, during which the participating countries organized various events. Swiss cabinet minister Alain Berset officially opened and visited the Swiss Pavilion. The first Salon Suisse, a series of events on architectural topics organized by the Pro Helvetia cultural foundation, took place at the same time.

Swiss Pavilion

“Orae – Experiences on the Border” (May 22 to November 21, 2021)

Salon Suisse

- September Salon “Kindred Spirits” (September 23–25, 2021)

- October Salon “Realities” (October 21–23, 2021)

- November Salon “Alterations” (November 18–20, 2021)

To find out more about the Swiss Pavilion and the Salon Suisse, see: biennals.chExternal link

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.