Swiss Pavilion in Paris celebrates 90 eventful years

Built in 1933 by Le Corbusier and decried by the proponents of traditional architecture, the Swiss Pavilion in the park of the International University Campus in Paris had a difficult birth. Since then, however, it has been home to several notable alumni.

To reach the Swiss-built student residence, visitors must first wend their way through the labyrinthine campus, past India House and Japan House. Nestled between the Danish, Swedish and Norwegian Houses, Le Corbusier’s creation does not immediately catch the eye, and it takes a connoisseur to know that it was built by one of the most famous architects of the 20th century.

“Before moving here, I had never heard of Le Corbusier,” admits Laura, a Belgian communications student, who has since read up on the Swiss-born architect. “My room, 16 metres square, is quite big and well designed by Parisian standards.”

One room in the Swiss Pavilion has been maintained as a prototype of the original and is open to visitors. The first impression is that of a monastic cell. The small bed was designed, like most of the furniture, by renowned French designer Charlotte Perriand. “In the other rooms we’ve replaced them with larger beds,” explains Monica Corrado, director of the Fondation Suisse/Pavillon Le CorbusierExternal link, which operates and maintains the student residence.

In one corner there is a small shower and basin. The better part of the room is taken up with the study area, with shelves and a desk in front of a south-facing bay window. Anyone working here wouldn’t be able to see much of Paris, but rather a stadium, and beyond that the famous Paris ring road, “which will soon be hidden by new pavilions under construction”, Corrado promises.

A hundred years ago visitors to this spot would have seen the ramshackle slum neighbourhoods of the city’s southern suburbs. In the aftermath of the First World War, politician André Honnorat dreamed of building a vast international student city on these 28 hectares of land as a kind of laboratory for world peace. Throughout the 1920s, the project gradually took concrete form.

Swiss chalet?

A few rare Swiss signed up to the undertaking, including the mathematician Rudolf Fueter, a professor in Zurich. But what kind of image did Switzerland want to portray of itself? By the early 1930s, Greece was building a quasi-temple with columns and a pediment in the nascent university campus, while Armenia was drawing inspiration from its national religious traditions. So what should Switzerland come up with – a rustic chalet?

The choice of architect would be decisive. A small group of academics led by Fueter lobbied to hire a fellow countryman who was stirring outrage among the advocates of academic architecture: Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier.

“There were two options: to support mediocrity or genius,” Hans Fehr from Bern argued before the Council of the Swiss House in 1930. “In the first case, we would need to organise a competition. But we are lucky to have Le Corbusier. We cannot let this opportunity pass in favour of a more democratic competition.”

With 16 votes to three, the Council decided to ask Le Corbusier to make a first sketch, without any commitment on either side, explained Corrado, who is writing a book on the Swiss Pavilion. “Once this sketch had been received and discussed, there was no further debate on the procedure (competition or not) and the mandate for construction of the house was given to Le Corbusier.”

Concrete pillars and glass façade

So much for the rules of democracy – modernism it would be. At the time, Le Corbusier was still smarting from his failure to win the League of Nations project in Geneva. He even filed a lawsuit against the League, accusing it of plagiarising his rejected plan. Was it to console him, then, that Fueter and his friends entrusted him with the Swiss Pavilion? Whatever the case, Le Corbusier was given free rein.

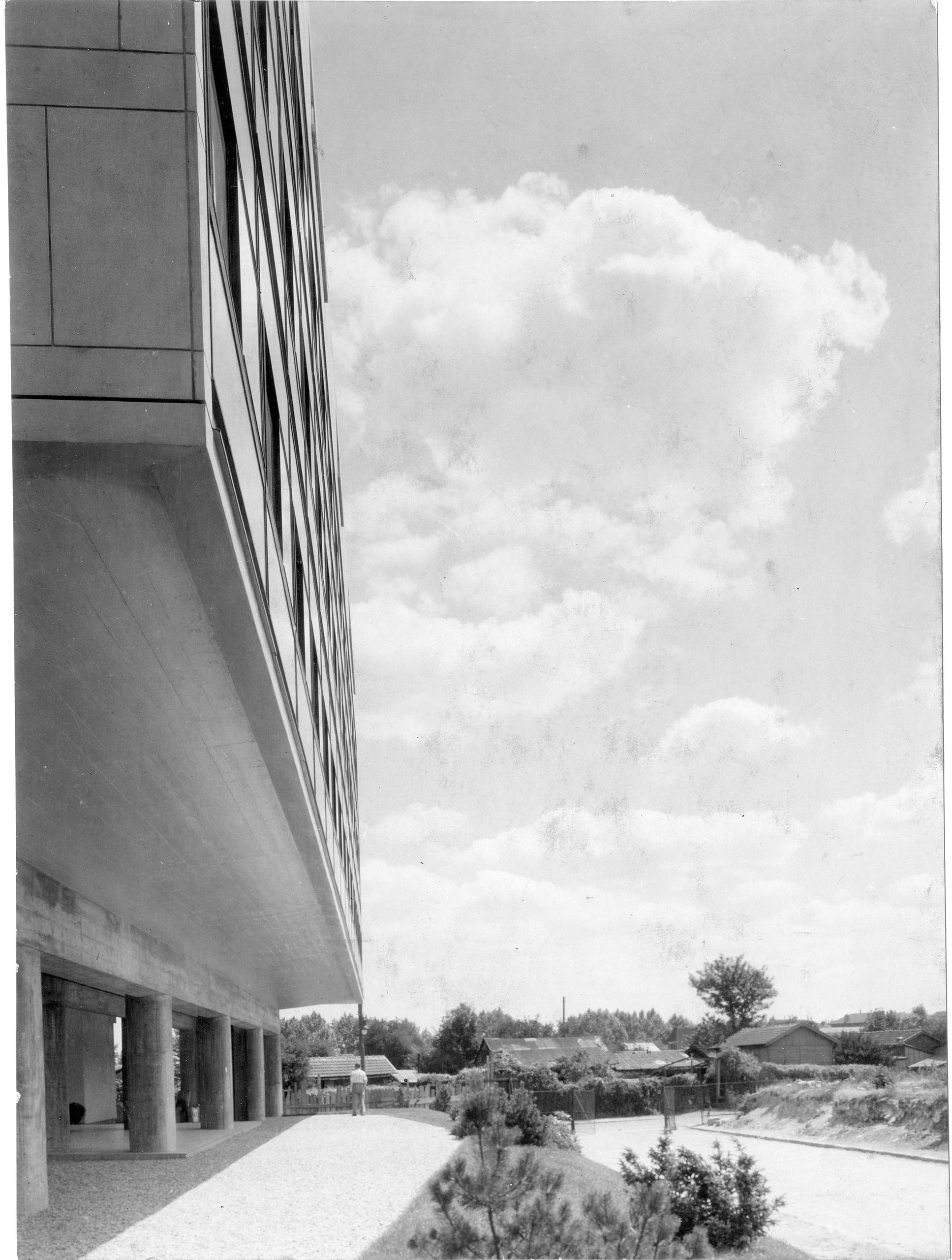

The building was erected on concrete pillars, or pilotis. Initially, these were to total only three, according to Ivan Zaknic in his book Le Corbusier – Pavillon Suisse: The Biography of a Building. This scanty number alarmed the Swiss authorities, who feared for the building’s stability. “People lacking in imagination still frequently ask: What are the pillars for?”, Le Corbusier was known to ask despairingly.

For Le Corbusier – as for his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, co-architect of the Pavilion – it was an opportunity to lay down the main features of social architecture that were to govern his future Radiant Cities in Marseille, Firminy and Berlin. These included pillars to free up ground-level space, a roof garden, a glass façade and a lounge with a curved wall, which he decorated with a photomural of his own design.

‘Dispiriting uniformity’

While Zaknic counts the Pavilion among “the hundred most remarkable buildings in the world”, the Swiss of the time were less convinced.

“We must react if we do not want the freedom and fantasy that make up the very essence of life to be transformed into odious and dispiriting uniformity,” wailed the Gazette de Lausanne.

“M. Le Corbusier was not content with declaring that national art no longer exists, with declaring war on all things traditional, […] with spitting on all of humanity’s most beautiful creations,” the Journal de Genève raged, denouncing a “Bolshevik” style.

On the whole, the building has aged well. During the Second World War, it housed the German army, which did not spare the premises. The photomural was damaged, so Le Corbusier, always very concerned about his “baby”, painted a gigantic canvas on the same spot – “à la Picasso”, smirked his detractors, although the comparison flattered him.

Over the years, the Swiss Pavilion has been home to several notable alumni. The renowned Swiss economic historian Jean-François Bergier lived here in 1956, while studying at the Ecole Nationale des Chartes. Years later he was to preside over the commission tasked with clarifying the relationship between Switzerland and Nazi Germany.

Then there was May 1968. The Swiss writer and investigative journalist Niklaus Meienberg – ever cutting in his criticism of official Switzerland – was then a student in Paris. He and other students sought to oust the Pavilion’s director and demanded self-management and the opening of the residence to women. Meienberg’s application for re-admission to the house was subsequently rejected, but the spirit of ’68 had won the upper hand. Women were allowed in, and students could take part in the management.

Today, at 90 years old, the building requires some care. “The bay windows made the rooms almost uninhabitable in the summer,” says Corrado, so they have been halved in size. “I recently met the managers of the Cité du Refuge, built by Le Corbusier at the same time, and we mainly talked about water damage,” she added. Nevertheless, this does not prevent the Pavilion from continuing to attract curious tourists and “pilgrims”.

Edited by Samuel Jaberg. Translated from French by Julia Bassam

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.