Swiss praised for pioneering work on Everest

When they crossed the Khumbu Icefall on Mount Everest in 1952, Swiss mountaineers “found the key” to the roof of the world, mountaineer and doctor Oswald Oelz tells swissinfo.ch. He also explains why they failed to go on and reach the summit.

The Khumbu Icefall is found at 5,486 metres on the Nepali slopes of Mount Everest not far above Base Camp. It is regarded as one of the most dangerous stages of the South Col route to Everest’s summit.

swissinfo.ch: How do you rate the achievement of the Swiss in 1952 from a mountaineering point of view?

Oswald Oelz: It was a fantastic pioneering accomplishment. At the time they were the best mountaineers in the world along with the French. [US mountaineer] Charles Houston had determined the Khumbu Icefall to be the way in to the Valley of Silence [the Western Cwm] in 1950 but wasn’t able to get over the icefall.

The Swiss managed this in 1952. The young climber from Geneva, Jean-Jacques Asper, excelled himself and crossed a wide crevasse in the upper section, which until then had been impassable. He abseiled into it and climbed up the sheer wall of ice on the other side in dynamic movements. Using the rope, a ladder could now be pulled over the crevasse – the door to the Valley of Silence was open.

swissinfo.ch: Is it true that the aim of the expedition was not to reach the summit but to advance up to the South Col at almost 8,000 metres? Or was it feigned modesty out of consideration for the British, who had been trying to reach the top for decades?

O.O.: It was definitely a pretext. If they made it to the South Col, the climbers wanted to continue to the summit. They also had oxygen equipment with them – which turned out to be unsuitable.

A Swiss success would have been a catastrophe for Britain, which is why in London members of the Alpine Club and the National Geographic Society were extremely nervous. Parallel to that, in 1952 the Brits were carrying out a test expedition on Cho Oyu [the sixth-highest mountain in the world, on the Tibet-Nepal border] with, among others, [New Zealander] Edmund Hillary. They were trying out their own oxygen equipment and developed the strategy that led to the first successful ascent of Everest in 1953.

swissinfo.ch: Were the Swiss aware of the historic dimension of their achievement? Did they realise that they had found the key to the summit, which to some extent subsequent climbers merely had to turn in the lock?

O.O.: It was a forceful turn in the lock when the 1953 expedition finally succeeded. But it was the Swiss who found the key: crossing the icefall, the Valley of Silence and the access to the South Col. In the process, they climbed the really steep flank of the Lhotse [the fourth-highest mountain on Earth, connected to Everest via the South Col] with relatively few fixed ropes.

Two things scuppered their chances on Everest’s Southeast Ridge: they hadn’t realised how vital fluid intake is when mountaineering. Lambert and Tensing didn’t have a kettle in their last bivouac at 8,400 metres – they had to melt snow in a tin can with a candle to be able to have a few sips. Already on the Lhotse flank they had an agonising thirst. Dehydration seriously affected their performance. In 1953, the members of the British expedition had drunk so much – on the insistence of their doctors – that Hillary had to have a lengthy pee on the summit, as he wrote in his autobiography.

Problem number two for the Swiss was the oxygen equipment, which they had been talked into taking by a Zurich professor. This could only be used when not moving – so only when sitting or standing – but not when climbing. This was because the professor had mistakenly believed that the human body could store oxygen.

swissinfo.ch: Mountaineering was then still in its infancy – technically but also medically. Were the climbers guinea pigs of sorts?

O.O.: Mountaineering back then was like being a voluntary guinea pig. The Swiss hadn’t undergone any corresponding tests. The British doctor Griffith Pugh was taking precise measurements during the 1952 attempt of how high fluid intake and flow rate must be. He thereby set out the first fundamental physiological principles, which were successfully implemented a year later.

swissinfo.ch: Switzerland’s Ernst Reiss and Fritz Luchsinger made the first ascent of the Lhotse in 1956, but this was overshadowed by the second and third ascents of Everest. The Lhotse has always been considered harder to climb than Everest. How do you rate their achievement?

O.O.: It was based on the fact that the Swiss had prepared the route up to the South Col with military precision. In the Lhotse gully Reiss and Luchsinger put on an alpine tour de force by climbing the very steep gully in the style of an ascent, mind you with extra oxygen. It was an operation that was carried out with utmost Swiss precision – they came back down unharmed, no frostbite or anything.

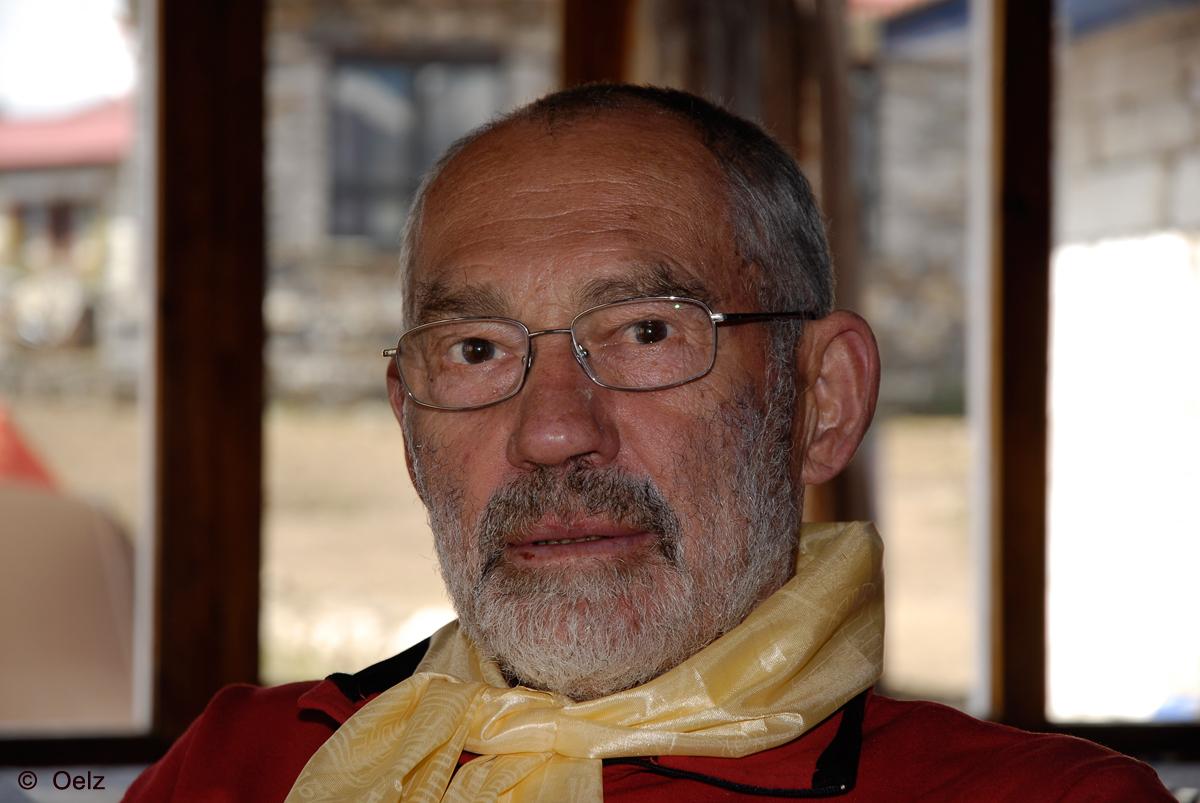

Oswald Oelz

Oswald Oelz, a 71-year-old Austrian, has lived in Switzerland since 1968. He was professor of medicine at Zurich University Hospital and head doctor of Triemli Hospital in Zurich. He is not only a pioneer of modern high-altitude medicine but also a successful extreme mountaineer in his own right.

In 1978, Oelz was the expedition doctor when Italian Reinhold Messner and Austrian Peter Habeler made the first ascent of Everest without additional oxygen. Previously, even high-altitude doctors had doubted that was possible. During that expedition Oelz also reached the summit, but with additional oxygen.

He is also the author of key works of climbing literature, including (translated from German) “With ice pick and stethoscope” (1999), “Headache mountains: A history of high-altitude medicine” (2001), “Everest-Lhotse: Swiss on Everest in 1952 and 1956” (2006), “Himalaya: Expeditions and films 1952-1971” (2007), “Oswald Oelz: Places where I lived before I died” (2011).

(Translated from German by Thomas Stephens)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.