Switzerland’s black market in sweet white powder

Imagine Switzerland at the turn of the twentieth century. People strap kilos of white powder to their bodies and head for the border. The alpine nation is the international hub for trade in this illegal substance. However, it’s not heroin – completely legal at the time – but the sweetening agent saccharin.

An extract from a 1913 novel helps tell the story: a respectable man frustrated by his business failures receives instructions on how to attach 15 kilos of a white powder to his body and smuggle it across the border. The scene takes place in a dingy backroom in the working-class district of Zurich.

The man follows the instructions and takes a train to Prague. He sails through customs and gets on with his lucrative business. But soon enough, the tragic hero of this story turns into a liar and a villain and gradually tumbles down an abyss of corruption, malice, barbarism and animalistic brutality.

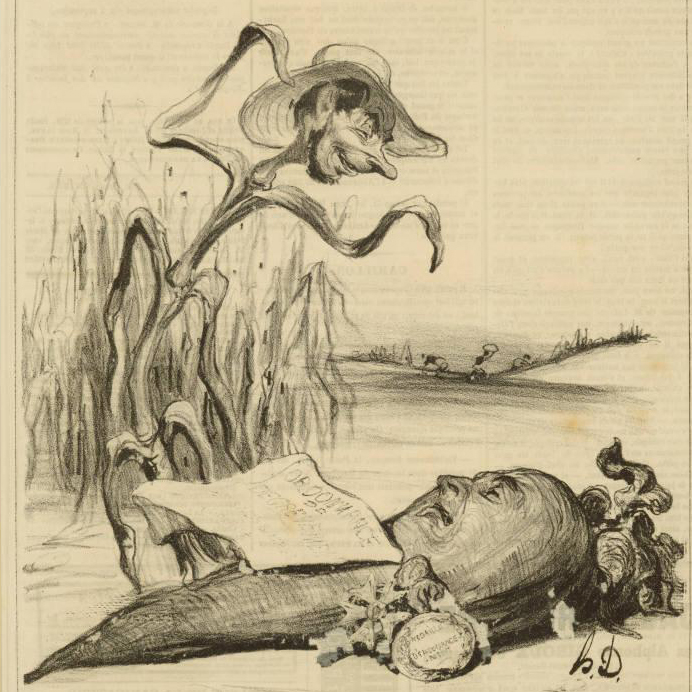

“The substance has me under control,” the protagonist of the story says. The demon beckons him: “Come on, come on. You will be rolling in money! I will make you rich.” Our smuggler is lost. “The demon that goes by the name of saccharin had stolen his soul.”

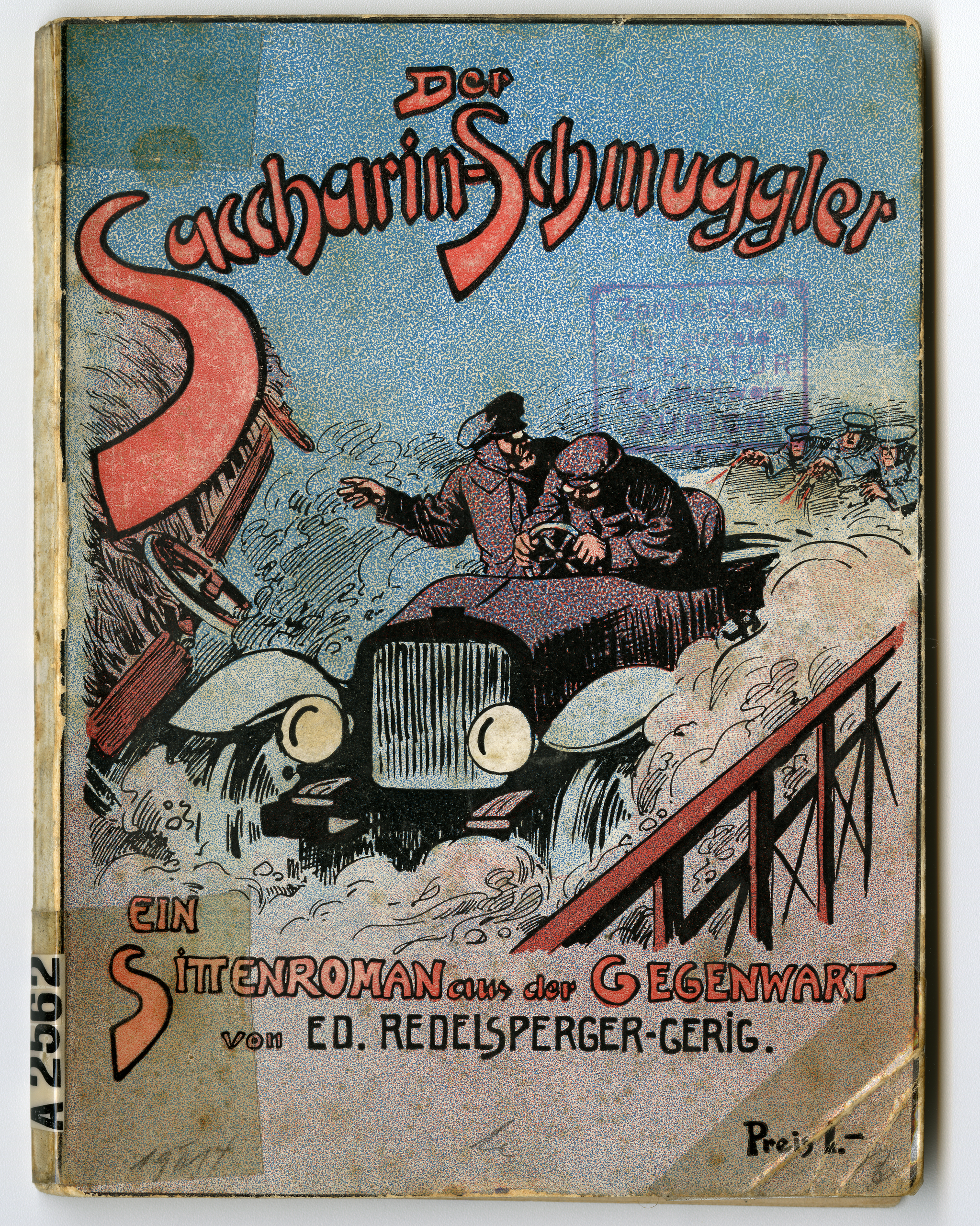

The reader could be forgiven for thinking that the demon was heroin, invented in 1898 and legally marketed as a cough syrup, or cocaine, which was also widely consumed at the time. But no, the demon portrayed by Eduard Ehrensperger-Gerig in Der Saccharinschmuggler (The Saccharin Smuggler) was an illegal synthetic sweetener that was taking Europe by storm. The little known author wrote this book to alert the Swiss authorities about the burgeoning trade.

The smugglers of Zurich

Tonnes of saccharin were smuggled out of Switzerland at the beginning of the 20th century, and across its borders whole communities lived off dealing saccharin. In fact, an entire housing estate in the Austrian village of Kappl near the Swiss town of Samnaun still bears the name Saccharin Estate in honour of the powdery substance that financed its construction. In rural areas, the smugglers were often hailed as heroes or seen as rebels against the border regime. Apart from money, they also earned fame.

In Switzerland, the illicit saccharin trade was also ubiquitous in cities. In 1912, a member of the Zurich city council claimed that around 1,000 people made their living dealing saccharin. However, the police’s hands were tied as the sweetener was legal in Switzerland. “The only option to get rid of the riff-raff was to expel those without identification papers,” the 1912 novel reads.

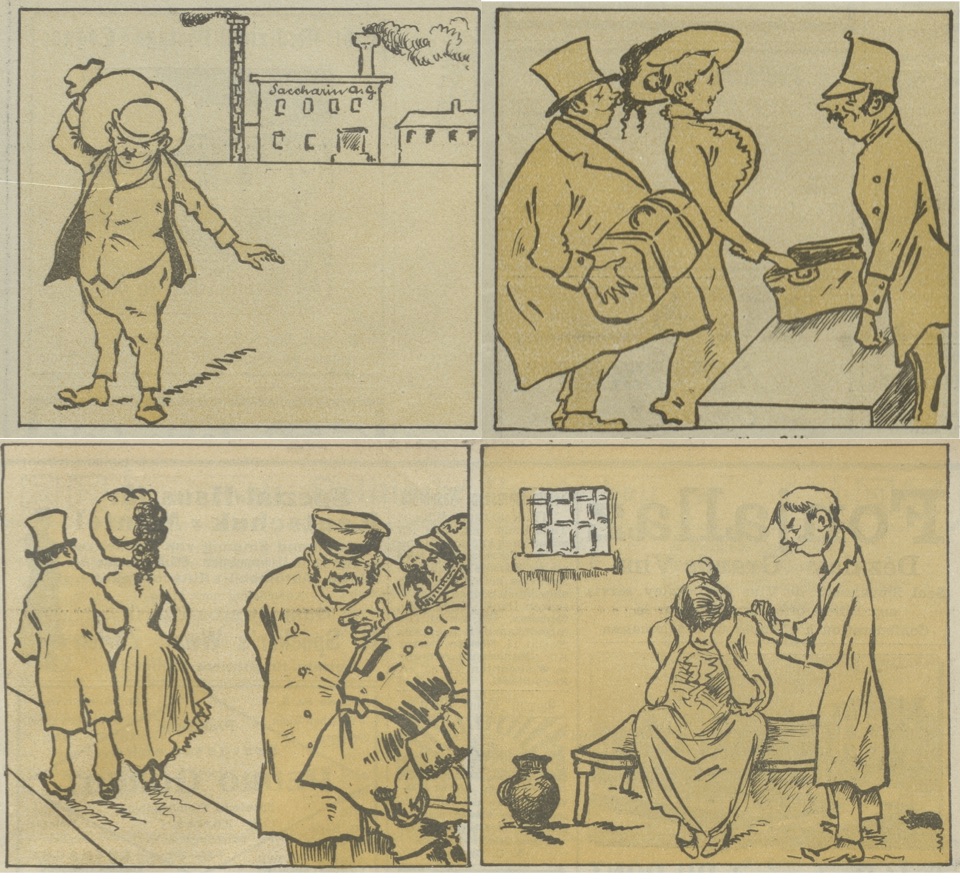

The smugglers carried saccharin under their clothes, sewed bags of it into their underwear, hid it in the toilet cisterns on trains or concealed it in false bottoms of cars. Others used rather daring ways to camouflage their precious cargo. One example was the supposed burial of Swiss people across the Rhine River in the German town of Konstanz. But the coffins that were carried across the border did not contain dead bodies, instead they held hundreds of kilos of saccharin. The culprits were caught and the story spread like wildfire across Europe. Another cunning method was to mix saccharin with wax to make large altar candles that were consecrated in the Einsiedeln Abbey. These were sent to Vienna where insider Catholics melted them and extracted the precious merchandise.

It was mainly poor people, sometimes women and children, who smuggled saccharin for middlemen – and often got caught. Newspapers frequently reported on foiled smuggling attempts. Maids, shop assistants and seamstresses were particularly vulnerable to the business as they needed the extra income.

For many, smuggling saccharin was viewed as a springboard to a criminal career. The Zurich daily newspaper Der Tagesanzeiger once reported that women had lost “their sense for regular work and their morale” and it would not take long for them to fall into the abyss. In 1912, Swiss border guards caught 931 women smuggling saccharin.

Sweet competition

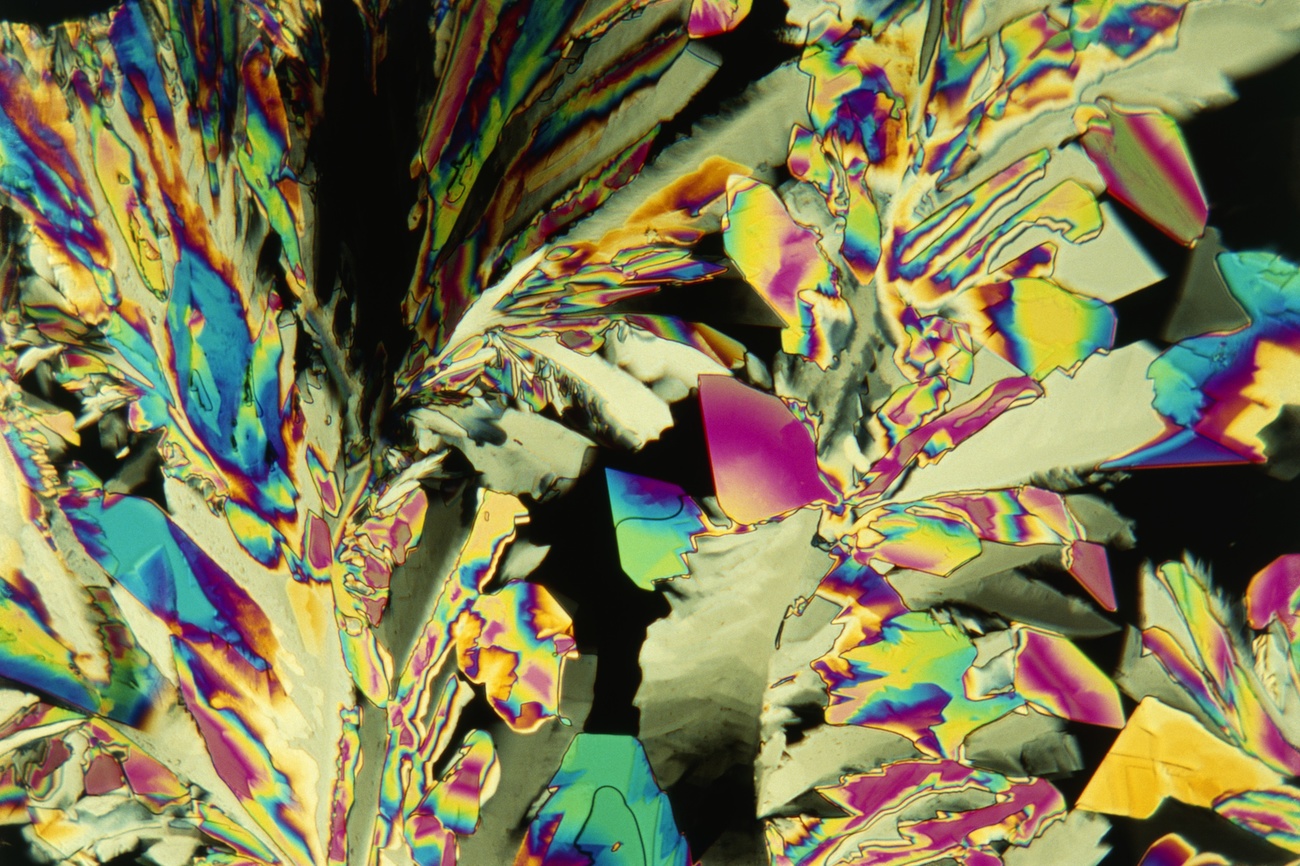

Ironically, saccharin originally came from Germany, which later became a smuggling destination for the Swiss. The German chemist Constantin Fahlberg discovered it by chance in 1878. After experimenting with tar in his lab, Fahlberg detected a sweet taste on his hands and was surprised to learn that the synthetic substance he had just invented was sweeter than sugar. In 1887, Fahlberg started producing saccharin in a factory. The sugar lobby was not pleased, particularly in Germany where lobbyists had worked tirelessly to protect local beet sugar against cane sugar imports from overseas. Punitive tariff duties had been in place on cane sugar since the mid-nineteenth century.

Now, local sugar production was no longer threatened by sugar from the colonies, but by an artificially produced sweetener from a lab. The German beet sugar lobby tried to convince the public to eat sugar by printing posters with slogans like “Sugar makes you strong” and by teaching the benefits of sugar in schools. The aim was to portray sugar as extremely nutritious and shame saccharin as the ‘sticky tarry stuff’. Nevertheless, saccharin consumption continued to rise throughout Europe. Bowing to pressure from the sugar lobby, a number of European countries passed laws that made saccharin a prescription drug at the turn of the century. From 1902, it was only available on prescription in almost every European country.

The production of saccharin was complex, which made it more expensive than sugar. However, the fact that it was 550 times sweeter than sugar made it cheaper overall. And so it became a popular surrogate for people from the poorer classes who were already used to drinking chicory coffee rather than real coffee, and ate margarine instead of butter. People loved putting saccharin into their fake coffees. And so, the black market for the white powder was born.

The police stepped up their efforts. Specialised ‘sweetener squads’ were set up to hunt down dealers just like today’s drug squads chase cocaine or heroin traffickers. Germany even established a “Central Office for the Prosecution of Trafficking in Artificial Sweeteners”. In the end, the authorities remained powerless and their work only led to the professionalisation of the trade and saccharin being mixed with gypsum or soda. The Austrian sociologist Roland Girtler even called the saccharin trade ‘the predecessor of drug dealing’.

Not illegal in Switzerland

Switzerland became the new country of origin of saccharin as the Swiss authorities did not make the sweetener illegal nor impose high taxes on it. The only other European country with similarly relaxed rules was the Netherlands. The Swiss sugar lobby did not feel threatened by saccharin because taxes on sugar were low to protect the chocolate industry from excessive costs. In Switzerland, the price difference between saccharin and sugar was insignificant which meant the sweetener did not put the trade in sugar beets at risk.

The fact that saccharin was illegal in other countries was of great benefit to Swiss businesses. The 1902 annual report of the pharmaceutical company Sandoz stated that saccharin’s prohibition abroad had opened “favourable perspectives” for Basel’s industry. Indeed, saccharin became increasingly important for chemical manufacturers in the years to come.

When the Swiss Food Act was amended in 1906, saccharin went from being rather insignificant in Swiss trade to becoming the most traded product, accounting for 34 percent of exports. This was primarily due to the fact that there was no competition from abroad and countries like the US or Japan, where saccharin was never illegal, continued to place big orders for the sweetener. However, almost half of the production went to middlemen who distributed saccharin through illegal smuggling.

End of an era

Soon after its rise, an organisation based in Geneva launched the European resistance against Switzerland’s illegal trade in saccharin. The White Cross, which was dedicated to fighting “the evils” of syphilis, alcoholism and drug addiction, took up the mission to crush the artificial sweetener. The organisation hosted several international conferences on how to control its smuggling. At the 1909 and 1911 conferences, Switzerland was accused of being a smugglers’ nest and a production site for illegal substances. Concessions were made thereafter and the chemical industry stopped deliveries to the middlemen who were proven to be smugglers, often only years after they had been convicted.

With the outbreak of the First World War, however, substitutes for all kinds of goods were in demand, putting an end to the golden era of saccharin smuggling. During the First World War, the satirical magazine “Nebelspalter” reported on a distressed saccharin smuggler who complained of being completely ignored by border guards. After the Second World War, the saccharin business experienced a quick revival. Smuggling to Italy was still lucrative, but the business completely fizzled out in the 1960s. In more recent years, the sugar industry has come under pressure again. This time around, however, it is not because of the palates of the poor, but because of the bellies of the rich. Now recognised as a calorie bomb, sugar is facing the threat of being highly taxed again.

Eduard Redelsperger-Gerig: Der Saccharinschmuggler: ein Sittenroman aus der Gegenwart. Gossau-St. Gallen 1913.

Roland Girtler: Abenteuer Grenze. Von Schmugglern, Schmugglerinnen, Ritualen und „heiligen Räumen“. Vienna 2006.

Christoph Maria Merki: Zucker gegen Saccharin: zur Geschichte der künstlichen Süssstoffe. Frankfurt/Main 1993.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!