Who will follow Federer and Wawrinka?

Is it the number of tennis courts? Is it GDP? Is it luck? Why do some countries have several male players aged 21 or under in the world’s top 500 and Switzerland doesn’t have one? swissinfo.ch speaks to tennis insiders and crunches the data in an attempt to uncover the secrets of producing world-class talent.

“If people expect us to produce another Roger or another Stan, they will be very disappointed,” a realistic Alessandro Greco, director of team performance at Swiss TennisExternal link, tells swissinfo.ch.

Indeed for the past decade Swiss tennis fans have been spoilt: Roger Federer (aged 34 and third in the ATP rankingsExternal link) and Stan Wawrinka (31 and fifth) have amassed shelves of silverware and won the Davis Cup and Olympic gold in doubles for Switzerland. Not bad for a country of just over eight million people.

Young talent

As of June 13, there are seven players aged 21 or under in the ATP top 100. Three are in the top 50.

The highest ranked is 21-year-old Australian Nick Kyrgios, ranked 19.

The youngest is 18-year-old American Taylor Fritz, ranked 63.

The next decade, however, isn’t looking so rosy. As of June 13, the next highest-ranked Swiss is 34-year-old Marco Chiudinelli (ranked 137) and there’s only one young Swiss player in the top 800 (19-year-old Antoine Bellier, ranked 527). In comparison, similarly sized or smaller countries such as Serbia, Belgium and the Czech Republic all have at least three young players in the top 500 (“young” meaning 21 or under).

What, if anything, is Switzerland doing wrong? In this article, we focus on the men. The situation for Swiss women isn’t so bleak, with 19-year-old Belinda Bencic and 27-year-old Timea Bacsinszky both in the top ten earlier in the year and 16-year-old Rebeka Masarova recently winning the Junior French Open.

Winning factors

Significant measurable variables that could influence a country’s sporting success include population size, affluence, popularity of the sport in question and the opportunity to play it.

Let’s start with a breakdown of the 33 countries that have produced the 84 young players who are ranked in the top 500.

No one factor here stands out as pointing to success. The best we can say is that relatively populous, relatively wealthy countries with a tennis tradition – Western Europe, the United States and Australia – are well-represented. A notable exception to that is Great Britain, which invented the game and pumps money into it but has only one young player in the top 500.

In absolute numbers, the United States is the winner with ten young players. In relative numbers, however, Serbia comes out top: four young players from a population of just over seven million. As we will see later, this is all the more impressive when you look at how few people actually play tennis in Serbia.

To what extent is Serbia’s success down to Novak Djokovic, the practically unbeatable world number one since July 2014? It’s hard to say – Switzerland hasn’t seen a “Federer effect” at the elite level – but one should remember that Djokovic trained at a Munich tennis academy for four years from the age of 12. Similarly, many promising young players from Eastern Europe and Russia move to tennis academies in countries such as Spain or the US.

Courting success

The US has a long tennis history, a well-oiled college sports system and 320 million inhabitants, but population goes only so far, as China and India demonstrate – not to mention no-shows such as Indonesia, Pakistan and virtually all of Africa.

This map shows the country of origin of all the young players in the ATP top 1,000. Every continent is represented – tennis really is a world sport – but Africa is noticeably underrepresented. Three Swiss players feature (ranked 527, 850, 918).

Obviously if a country has hardly any courts, for cultural or economic reasons, the chances of producing a world-class player are low – unless they move abroad. This could be one reason why the data for Europe doesn’t really prove a correlation between the number of tennis courts per inhabitant and an ability to produce talented young players:

Germans have 47,000 tennis courts to choose from whereas Italians have 10,000, Spaniards 5,800, Swiss 3,600 and Serbs only 1,500. When adjusted per capita, as in the chart, the data suggests it should be easier for northern Europeans to get a court.

Perhaps cheaper courts in successful tennis nations Italy and Spain are teeming with tennis-mad fans, some of whom eventually turn pro? This seems to be nearer the truth. Although, again, there are glaring exceptions: according to the data from Tenniseurope.org, Serbia has only 2,500 licensed players and 13,600 recreational players, a tiny fraction of the number in most other European nations.

Note that Switzerland is in the middle in both charts, with some 600,000 players fighting over 3,600 courts.

However, this still doesn’t explain why Switzerland isn’t producing many strong young players while similarly sized – and equipped – neighbours are.

“I don’t think there’s a reason. I don’t think we’re doing anything wrong,” said Alessandro Greco at Swiss Tennis. “For male players in particular it is very, very difficult to get into the top 100. The average age [for a top 100 player] is 27-28, so it’s a really long way to go.” In our interview, Greco discusses the role of schools and parents in forming a world-class athlete – and how Switzerland’s high quality of life and lack of adversity could be a disadvantage when it comes to sporting success.

More

‘Professional tennis in Switzerland is expensive’

Life at the bottom

Switzerland’s most-promising young player is 19-year-old Antoine Bellier from Geneva. He turned professional last year and is currently ranked 527, having worked his way up from 691 at the beginning of the year.

The 1.96m (6’5”) left-hander cites Roger Federer as a big influence – “when you see him play you just want to pick up your racket!” – and says his aim is to make it into the top 20 or 30.

But it’s a long road, paved with mental and physical obstacles. For now, Bellier is just focusing on improving his game and hasn’t set himself any specific targets. “I can’t say ‘in one year I want to be in the top 100’,” he told swissinfo.ch during a training pause at the Geneva Country Club.

“I travel a lot, but when I’m in Geneva, every day I do one session of physical training and then two sessions of tennis. So that’s maybe five or six hours a day. I travel maybe 30 weeks a year – that’s around 30 tournaments a year.”

Without wishing to demoralise Bellier, at the same age Federer was ranked 21 and Wawrinka 55.

“I think if I’m 26 and ranked 400, I’ll probably stop, because I don’t want to play Futures [the lowest circuit] for ten years – it’s not so easy with the money,” Bellier said. The winner of a Futures tournament earns around $1,000 (CHF950) and a first-round loser around $100, not including travel and other expenses. Sponsorship and help from parents is usually the only way to get through the early years as a tennis pro.

In a sobering reportExternal link, the ITF revealed that only 336 men and 253 women made a net profit playing tennis in 2014. In addition, highlighting the inequality in the modern game, the top 1% of ranked male players earned 60% of the total prize money.

Distractions

Bellier’s coach, Sonny Kayombo, a former tennis professional from France, is convinced it’s just a matter of time before more young Swiss make a name for themselves.

“Some very good young players ranked around 1,000 are coming up. I’m sure that if we were to do this interview in one year, Antoine will not be the only player in the top 800,” he told swissinfo.ch.

When asked why there doesn’t seem to have been much of a Federer effect in Switzerland, he said there had actually been one in Switzerland’s roughly 900 tennis clubs.

“A lot of young players want to become the next Federer – or Wawrinka – but it takes time. The number of licensed players in Switzerland is increasing every day,” he explained.

“But there are other reasons. Roger Federer is such a great player, but there are other great sports stars in Switzerland, in skiing for example. So people go skiing and do other stuff.”

Greco echoes this, saying that if he had a talented son who came to him and said he wanted to become a professional tennis player, he would tell him to play ice hockey or football instead. “I think it’s easier to get to the top.”

The grand conclusion? Money and number of players certainly help for national sporting success, but they seem to go only so far. National federations can help a talented player get into the top 100 or 200, but breaking into the top 20 seems to be largely down to an individual’s natural talent and motivation.

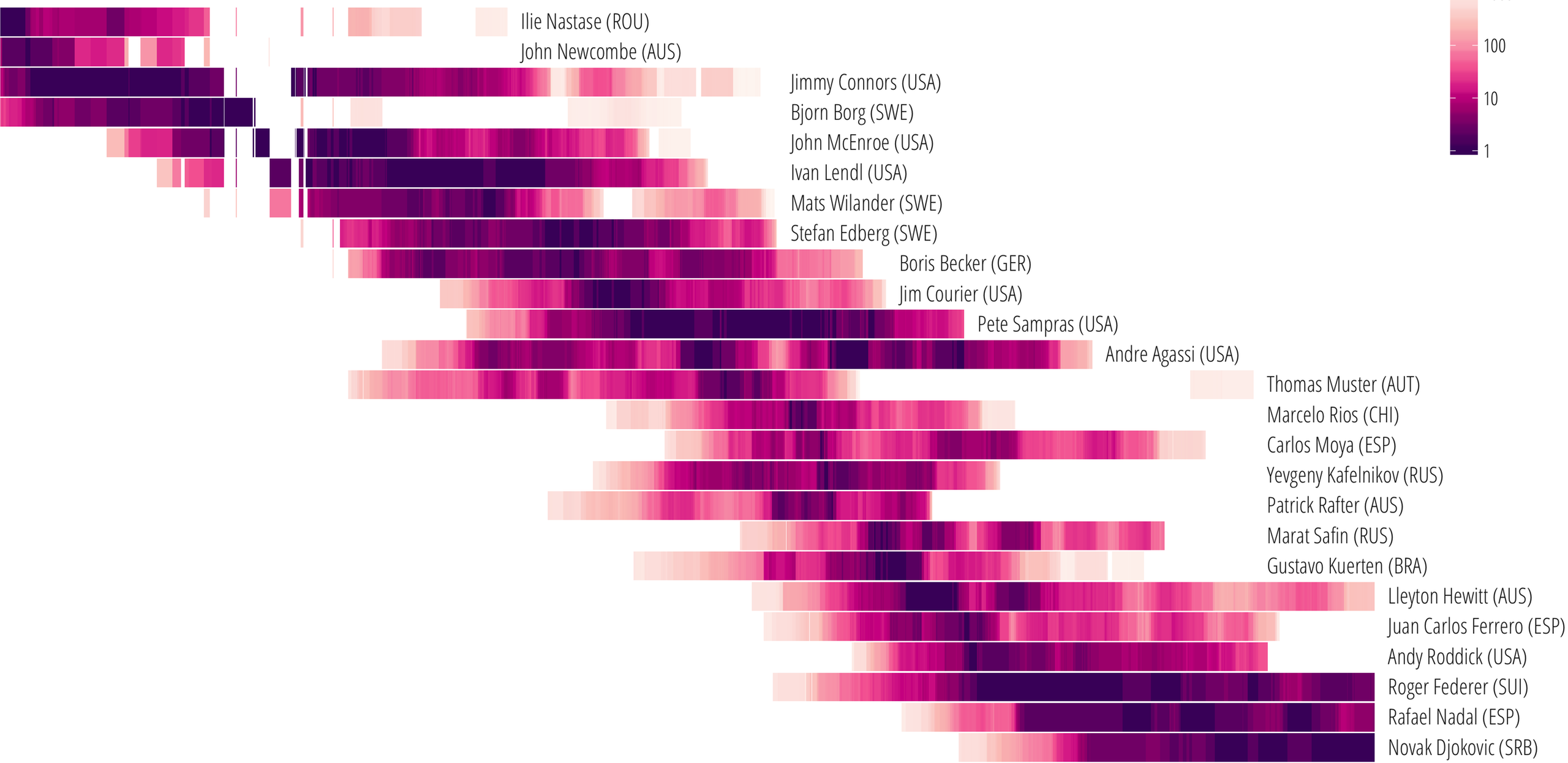

So how did Switzerland produce Roger Federer and Stan Wawrinka? It just did. It got lucky. These things go in cycles. Just look at Sweden, which a generation ago produced Björn Borg, Mats Wilander and Stefan Edberg, each of whom won at least six grand slam titles. Today there isn’t one Swedish player – of any age – in the top 100.

As Sonny Kayombo put it: “What Roger and Stan have achieved – wow! People don’t realise the chances of Switzerland producing two players like that.”

How are promising young tennis players developed in your country? What’s the secret to producing world-class players?

Discuss this with us in the comments.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.