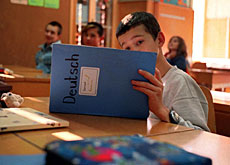

Testing time for immigrants

The town of Ostermundigen is the first in Switzerland to introduce written language tests for those applying for Swiss citizenship.

Supporters say the tests will improve integration, but critics say written examinations could be discriminatory.

“We have around 22 per cent of foreigners in our town,” said Ursula Norton of Ostermundigen’s local government. “And very often, when we interviewed candidates for naturalisation, we found that their knowledge of German was very poor.”

“We wanted to do something for integration, and we thought we would start with the language,” she told swissinfo.

Local power

In Switzerland, immigrants wishing to become Swiss must apply through their local communities, and the main decision-making process takes place at local level.

This means that towns like Ostermundigen have a great deal of freedom to decide on the criteria for citizenship.

The new language test has been developed with the help of the Migros adult education centre and is made up of multiple-choice questions written in high German rather than Swiss German.

Although it is not an enormously difficult test, it has attracted criticism. Stefanie Gass, an ethnologist specialising in immigration issues, believes written tests could be unfair to some candidates.

“Immigrants in Switzerland can’t speak German not because they don’t want to, but because they don’t have the chance to,” Gass told swissinfo.

“Often they are just at home with their children or working cleaning empty offices at night, so they don’t get the chance to practise.”

Gass also questions the concept of introducing obligatory language tests at the point at which an immigrant applies for citizenship.

“Remember you have to live here for 12 years before you can apply,” she explained.

“We should be asking what they were doing all those 12 years; did they have the chance to go to language classes?”

Integration failures?

In Ostermundigen, candidates for citizenship are offered the chance of language classes, but they do have to pay for them. However the town will refund half the money if the students attend at least 80 per cent of the classes.

But Ursula Norton agrees that integration efforts when the immigrants first arrive in Switzerland could be improved.

“We give them written information when they first arrive, and we send out some fact sheets about the community,” she explained. “Then if they want more they can ask here and there, but that’s about it.”

Life in Switzerland

A visit to one of Ostermundigen’s language classes is an interesting experience. It is clear that, along with the language, Swiss cultural attitudes are being taught too.

Students work from a book called ‘Life in Switzerland’. Exercises include looking at drawings of two children, one sitting quietly in a corner, the other throwing building blocks up into the air.

Asked to describe the first child, most students suggest ‘quiet’. In fact the answer is ‘good’. For the second child, the students suggest ‘playing’. But no, the teacher explains, a child throwing building blocks is a ‘badly brought up’ child.

This response draws uneasy laughter from the students, most of whom are women.

“I am nervous about this test,” said Saibua Grädel from Thailand. “I don’t know what they are going to ask me about, what they will test me on. And German is a very difficult language.”

Finances investigated

She is perhaps right to be nervous. When it introduced the language tests, Ostermundigen also introduced a stipulation that candidates for citizenship should not be in debt.

“You do not get to be Swiss if you have debts,” said Norton. “If someone has a credit at the bank for a car or whatever, we will check… they are paying off the debt responsibly.”

Norton admits however that she herself is not entirely comfortable with such investigations. “It’s an image of Switzerland,” she said. “A Swiss person doesn’t have debts, never does anything illegal and of course that’s not really true.”

“But maybe we just don’t want anyone new that doesn’t come up to that image.”

Selection criteria

At the national level, officials do recognise allowing local communities to set criteria for citizenship can be problematic.

“It’s all about the competence of the local community,” said Roland Schärer, head of the citizenship section at the Federal Office for Immigration and Integration.

“They are autonomous, and that leads to unequal treatment. Of course I would prefer one Swiss citizenship [procedure], but that will take decades.”

In the meantime, candidates for citizenship in Ostermundigen will continue to study for their language tests. The fact that they are learning German is positive, as knowledge of the local language is an important key to feeling integrated in a new country.

Nevertheless critics are not convinced, and suspect that Ostermundigen and other communities are simply introducing extra requirements for citizenship in a bid to reduce numbers.

“It doesn’t look like a vision of integration to me,” said Gass. “It looks more like a criterion for selection.”

swissinfo, Imogen Foulkes

Criteria for citizenship vary widely in Switzerland. The city of Bern ‘assumes’ candidates are integrated after 12 years and approves them almost automatically.

In other towns, candidates undergo extensive interviews about their lives, their work, their financial situation and their knowledge of Switzerland.

The German capital, Berlin, introduced written tests two years ago, and says they are successful; 80% of candidates pass.

But critics say written tests should not be introduced unless candidates have benefited from integration policies, including free language classes.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.