The Buchenwald children – a forgotten history

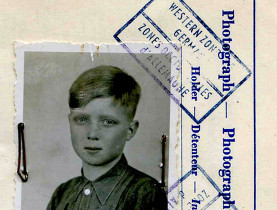

At the end of the Second World War, the Swiss offered to take in young concentration camp survivors but were in for a surprise when the group from Buchenwald arrived.

Alighting the train in Basel in summer 1945 were around 370 Jewish young people, not the children they expected. Aid organisations were unprepared, but the 16-22 year olds tried to make the best of the situation.

In 1945 there were millions of displaced people living in the former Nazi-occupied territories. Switzerland, following the example of other countries, offered to house up to 2,000 children from the Buchenwald camp in Germany for six months.

But this was not just for humanitarian reasons.

“Switzerland had an image problem after the war, they had to justify their neutrality and they were very interested in having better relations with the Allies and that’s why they looked for a way to cooperate,” historian Madeleine Lerf told swissinfo.ch.

Lerf’s book, Buchenwald Children, a Swiss Relief Operation, based on her PhD thesis and published earlier this year, is the first in-depth look at the episode by a researcher.

Switzerland had a long tradition of helping children. But what the government-backed Schweizer Spende (Swiss donation) and Swiss Red Cross, the two main aid organisations involved, did not realise was that hardly any young children had survived the harsh conditions of the camps.

Hostile reaction

The reaction to the arrival of the young people, who were mostly from eastern Europe, was very hostile, Lerf explained.

“The authorities seriously thought about sending the older ones back to Germany. And the reason why they didn’t do it in the end was political because they knew it would cause a big scandal,” she said.

After quarantine, the Swiss authorities sent one half of the group, who had been on their list, to a Red Cross camp. The other half, considered to be in the country illegally, were kept in an army camp until it was decided what to do with them.

Army camp residents of the time have, in interviews, shared different memories. Some were very happy to be in places with beds and white bed sheets.

“But contemporary texts state that some young people were very offended, they did not understand why they were sent to another camp with fences around it and soldiers taking care of them.”

The camp soldiers had little interest in their charges and looked at their job as defending Switzerland. Many felt Switzerland had been cheated. Anti-Semitic feeling was not uncommon.

Different image

“Another problem was that people were prepared for near skeletons, very weak people. But in fact when the group arrived they already looked quite strong because they had been fed by the Americans for two months,” Lerf said.

“They didn’t fit into the picture they had. That made it even more difficult for people to understand that they were fragile and needed help.”

The camps had a strict regime, with the commandant watching over the youths at mealtimes with a clock. Those who filled their pockets with food from the kitchen, a reflex after so many years of starvation, were considered thieves.

However, a lot of the civilian helpers, many of them women, tried to look after their charges, finding food and other necessities when, as sometimes happened, supplies became low.

The young men and women, often kept separate, nevertheless managed to have fun and fall in love, thus slowly taking steps back into normality. Some pursued an education, others learned a profession.

Jewish groups

Some of the “illegal” group were later handed on to Swiss Jewish organisations.

These had wanted to be more involved from the start. During the war Switzerland had applied pressure on them to look after Jewish refugees coming into the country.

But Bern wanted to keep hold of the Buchenwald project. The Jewish organisations therefore grouped themselves together and lobbied for more say.

“For them it was very important because they knew they had lost so many people in concentration camps during the war and they felt a big need to take care of these survivors,” Lerf said.

Unrealistic expectations

Indeed, squabbling between the authorities and relief organisations over who was responsible and who should pay dogged the Buchenwald relief action from the start, giving the project a chaotic nature. Part of the problem was that the Swiss had not fully thought out the plan, Lerf says.

They also only accepted the Buchenwald group for six months. This was later extended by another half a year because most of the young people were stateless Jews, with nowhere to go.

Those who wanted to stay were not allowed to do so. “That might sound strange today because they were invited and there were only around 370 people,” Lerf told swissinfo.ch.

“But Switzerland based all its refugee policy during the Second World War on the transmigration principle which meant it could only house refugees for a limited time and none could stay permanently. This principle was held up after the war and also applied to the Buchenwald group.”

Different destinies

After a year, some of the Buchenwald group, spurred on by the Jewish groups, left for Palestine. Others went to relatives in the United States or Australia. Around 30, some of whom were suffering from tuberculosis or had sponsors, were able to stay. But not all were so lucky.

“Even someone married to a Swiss woman was forced to leave because back then the woman’s nationality didn’t count. They went to Australia,” the historian said.

Lerf says that the case of the Buchenwald children – as they always remained for those involved – is not often discussed in Switzerland.

However, it has gained interest abroad: on October 29 the historian is addressing the Buchenwald Memorial foundation in Weimar in Germany on the subject.

“In France there have been exhibitions and meetings of people involved, but not in Switzerland. It’s a largely forgotten episode.”

“Buchenwald Children, a Swiss Relief Operation – humanitarian commitment, political calculation and individual experiences” was published in German this year.

It is part of a series arising from The Archives of Contemporary History at the Federal Institute of Technology Zurich,.

Lerf did her doctorate at Basel University. The idea was suggested by her professor, Georg Kreis, who knows a daughter of one of the women involved in the project. This woman left behind many documents.

In the course of her research, Lerf travelled abroad to Israel, Poland, Germany and Australia. In some locations she conducted interviews with former Buchenwald children.

At the end of the war, the German SS brought Jewish, Russian, Ukrainian and Polish adolescents to Buchenwald from the extermination and forced labour camps in the east. For the most part, their families had been murdered and their homes destroyed. Their survival depended on their being able to perform forced labour.

The SS sent thousands of teenage Jews, Sinti and Roma to Auschwitz, having classified them as “unable to work”. Around 1,600 adolescents and children died in Buchenwald from illnesses, beatings or shootings.

Some adolescents were protected by inmates, who set up, for example, a “bricklayers’ school” and convinced the SS to allow shelters. Among those gaining refuge was later the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel.

When Buchenwald was liberated on April 11, 1945 there were 904 children and adolescents among the 21,000 inmates.

Source: Buchenwald Memorial

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.