The conquest of the “Virgin” peak

It must have been an odd sight: Two well-to-do brothers stroll into town and hire a couple of hunters to lead them up a mountain the peasants had never seen before.

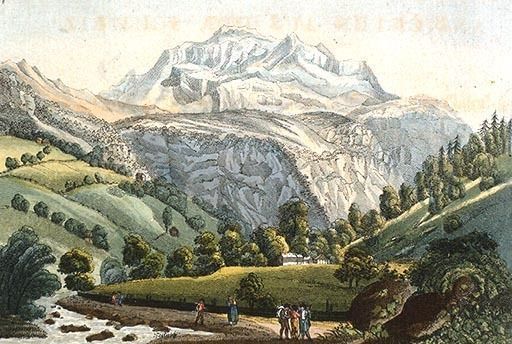

That scene played out exactly 200 years ago. The ensuing climbing party, headed by the Meyer brothers, became the first to reach the top of a 4,000-metre-high mountain in Switzerland – the Jungfrau (German for virgin or maiden).

Johann Rudolf and Hieronymus Meyer, sons of a wealthy textile merchant, were keen to climb the jewel of a peak that could be seen from far and wide in northern Switzerland where they lived.

It was a bold, if not mad idea at the time. Climbing mountains was in its infancy, and the so-called golden age when mountaineering became a sport wouldn’t begin for another half century.

The Meyers were led to believe that the best approach to the Jungfrau was from the south, so they set off on an overland adventure, crossing hill and dale and mountain pass before reaching the poor alpine village of Fiesch in the upper Rhone Valley.

It’s likely they didn’t realise that no one in the village had ever seen the peak they sought, cut off from view as it was by the steep slopes of intervening mountains, and guarded by the Alps’ longest glacier, the Aletsch.

“The guides Joseph Bortis and Alois Volker never saw the Jungfrau before and so it must have been a huge challenge. They were looking for money so they agreed to climb the mountain even though they had no experience,” Kilian Volken told swissinfo.ch.

Guiding dynasty

Mountain guide Volken has lived all his life in Fiesch and is a direct descendant of Volker. His ancestor became the first in a long line of guides that hasn’t stopped with Volken. One of his nephews is carrying on the tradition.

If Volker and Bortis were after money, the Meyer brothers had likely inherited their father’s passion for Swiss geography. After making it rich from his silk ribbon factory Johann Rudolf senior financed the first map series – known as the Meyer-Weiss Atlas – that covered all of Switzerland and was based on a scientific survey.

The brothers may have used the atlas not only to find their way to Fiesch, but also to plot the route to the summit, even though the maps lacked any detail on the glaciated, high alpine region.

“We advanced over the ice and snow masses hanging down from the Jungfrau…” the brothers wrote in their notebook about the events of August 3, 1811.

“What we thought was an unbroken snowfield proved to be an optical illusion; suddenly under our boots we saw a drop of around 40 to 50 feet, which we were only able to master with difficulty… the way down to the foot of the Jungfrau summit was a narrow glacier ridge or saddle.”

“The highest point”

Led by Volker and Bortis, and with the help of a few porters, the Meyer brothers finally overcame the obstacles and got to the peak:

“Once the most difficult step had been taken, the way to the snow slope opened up and after a few more steps, we arrived on the highest point of the Jungfrau massif. It was just after two in the afternoon.”

But once they returned home, they had difficulty convincing anyone of their accomplishment.

“A year later in 1812 one of the brothers did it again to prove that he had been to the top. The same thing with the first ascent of the Finsteraarhorn. One of the Meyer brothers took part. It took about 30 years for people to believe they had been on top,” explained Peter Brunner, author of a book, Jungfrau – 200 years Jungfrau Summit, commemorating the anniversary.

The book contains original passages from the Meyers’ notebook, and a record of the most remarkable Jungfrau ascents over the past two centuries.

Accessible today

Today, the Jungfrau is one of the most accessible 4,000m peaks in the Alps, thanks to the Jungfrau railway which runs through tunnels to end only a few hundred metres below the summit.

Volken says he has personally taken at least 300 people to the top of the iconic mountain in his 35 years of guiding. He thinks the same number go up in an average year.

“In general it’s not too hard but it shouldn’t be your first 4,000m mountain,” added Richard Bortis, a Fiesch mountain guide who is a descendant of Joseph Bortis, the other hunter-climber to go into the record books. “You need a little bit of experience to climb with crampons in the rocks. It’s not a very difficult ascent.”

However, one thing has not changed, according to Brunner. “In German we say the Jungfrau is the quintessential mountain because it’s the only one in the entire range that is brilliant.”

The mountain resorts around the Jungfrau use its name to market tourism in the region. The mountain has also lent its name to the regional railway company, which runs the popular tourist train to the saddle just below the summit – the Jungfraujoch – and most ski lifts in the area.

The tourist railway trip to the “Top of Europe”, as it’s billed, was first opened nearly 100 years ago, in 1912. Last year, 672,000 people paid for the pleasure to make the journey to the saddle at 3,454 metres above sea level.

The Jungfrau became better known in 2001 when Unesco listed the Jungfrau-Aletsch-Bietschhorn high alpine area as a natural World Heritage Site.

The Jungfrau is a popular mountain for many people wishing to climb a 4,000m peak due to the ease of access.

Hundreds of people make the ascent each year, with most taking the train to the Jungfraujoch, staying the night in a nearby mountain hut before setting off for the 4,158-metre-high summit in the early hours of the following morning.

However, the climb is not without peril. Fresh snowfall is not unusual at this altitude even in high summer, increasing the risk of avalanches on its steep flanks.

In a highly publicised incident in July 2007 six army recruits fell 1,000 metres to their death, carried away by an avalanche. Six soldiers and the two guides escaped unharmed.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=855f1d9f)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.