The hills are alive … with Romansh monsters

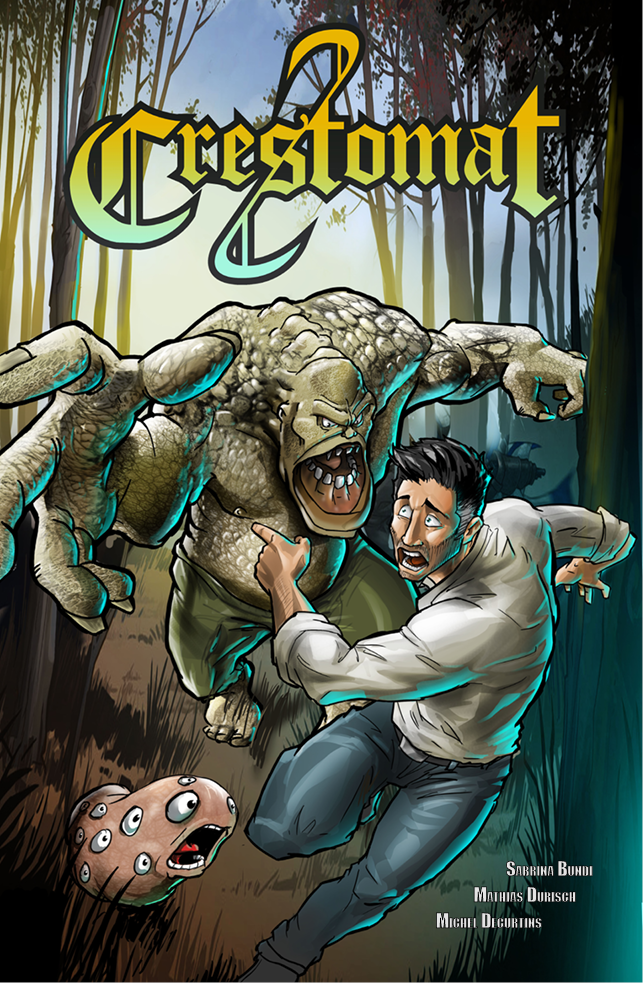

Featuring nightmarish creatures and a very confused human, Il Crestomat is the first online comic written in Romansh. It aims to pass traditional myths on to a new generation and promote interest in Switzerland’s least-spoken national language.

“The Metta da fein – the mute from the hay – cuts the feet off children who walk through the high grass fields,” artist Mathias Durisch says with a worrying smile. “People used to tell their children not to walk through the fields otherwise the Metta da fein would get them. I thought she could be a great angry character in the comic.”

The free online project began in Chur, the capital of canton Graubünden in eastern Switzerland, home to most of the 60,000 or so people in the world who can hold a conversation in Romansh.

“It was Indiana Jones!” says the comic’s writer Sabrina Bundi, a journalist at Romansh-speaking Swiss public radio, RTR. “We had just seen Indiana Jones and thought it would be cool to create an adventure.”

Co-writer Michel Decurtins, also a journalist at RTR, jumps in. “Actually it all started with the word ‘Crestomat’, which doesn’t exist but popped into our heads out of thin air. It just so happened that we’d just seen Indiana Jones.”

Bundi, 31, and Decurtins, 37, are the creators of Il CrestomatExternal link, a “redefining”, as Decurtins put it, of the Rätoromanische Chrestomathie, a collection of Romansh texts going back almost 500 years. They write the scripts and the dialogue and send them to Durisch, 37, in Zurich to draw.

‘Epic saga’

It turns out to be difficult talking about the plot without giving too much away. Indeed a couple of times one of them accidentally reveals future twists that haven’t yet been published, triggering a sudden “pssshtt!” from the other.

“Dr Clau, an invented character from our world, ‘drops’ into a mysterious world where the myths of the Chrestomathie are alive and fighting each other for land…” says Bundi, setting the scene for the first issue, which appeared in November.

Future issues are “roughly bimonthly”, with the next one due “soon” and the 30th and final issue planned to appear in around five years. “An epic saga,” Bundi says of the expected 600 or so pages.

A new issue always appears first in Romansh and is then translated into German, Italian and English a few weeks later. Being online, the comic is not only cheaper to make but can also reach a much wider audience.

Decurtins doesn’t think providing the comic in other languages risks people bypassing the Romansh.

“We don’t want Romansh-speakers to not read it in Romansh – and they won’t, because there are many language jokes that you simply cannot translate and are only funny in Romansh. There’ll probably be hardly any German-, Italian- or English-speakers reading the Romansh, but when they have it in their own language, they get Romansh culture through the back door, so to speak.”

Nightmare fuel

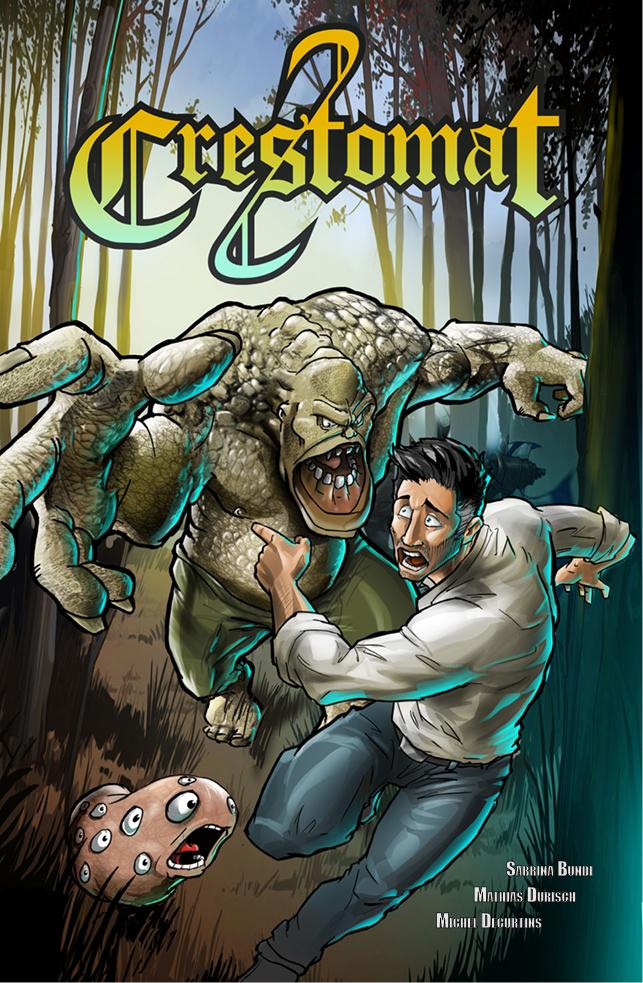

“The most special figure is the ‘Buttatsch cun îgls’ – the paunch with eyes!” says Bundi, referring to a moving, talking cow’s stomach covered in dozens of eyes. If the Metta da fein isn’t nightmare fuel, this definitely is…

“Our paunch is sweet!” Bundi says protectively. “Helpful, slightly clumsy but very kind. He’s an original Graubünden figure.”

She points out how, at the end of every comic, there are extracts from the original Chrestomathie, “so you can see for example how the original Buttatsch was described”:

Other traditional characters in the first issue include a “glimari”, an ogre with a passing resemblance to The ThingExternal link in Marvel’s Fantastic Four.

“We discussed the style and what it should look like, and we were all convinced that it should be a modern comic, so it could have the Marvel aesthetic,” says Durisch.

“I used to like those comics when I was young, so it’s a lot of fun to draw them,” he adds, estimating that once the script and speech bubbles arrive from Chur, it takes him about eight hours to draw one page.

More

Romansh culture as you’ve never seen or heard it

Decurtins says one of the main aims of the project is to remind people of these stories, “because they will be forgotten”.

“I don’t want my children to have to read 7,000 pages of very, very heavy text just to know some of our myths,” he says. “But it’s also for the world to get to know Romansh culture better.”

Unlike the main characters found in, say, the Brothers Grimm or Lewis Carroll – known to most Europeans – not all Romansh-speaking children are familiar with the colourful cast of the Rätoromanische Chrestomathie.

“I knew some of them,” Decurtins says. “I hadn’t heard of the Buttatsch until Romansh Studies at university. But children from the Surmiran part of Graubünden grow up knowing about paunches with eyes that roll from the mountains…”

Idioms

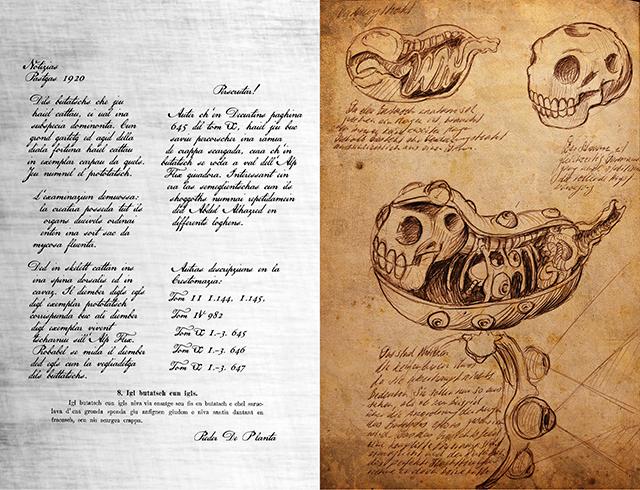

When discussing Romansh, sooner or later the issue arises of idioms. Romansh is divided into five of these regional varieties – Sursilvan, Sutsilvan, Surmiran, Putér and Vallader – each with its own local characteristics.

Il Crestomat features all five. “The Buttatsch originates from central Graubünden, from the Surmiran part, so he speaks Surmiran,” Decurtins explains. “Dr Clau speaks Sursilvan because he’s the main character and we speak Sursilvan! But the rest of the characters speak Putér, Vallader and other idioms.”

Like Bundi and Decurtins, Durisch was also born in a Sursilvan-speaking part of the country, but unlike them his first language is Swiss German.

“Both of my parents speak Romansh but not together. So I learnt it as a child but German was spoken at home. I understand everything but don’t speak it so well,” he told swissinfo.ch in Zurich, where, by day, he is head of design for a research and development company.

“I was really excited when Sabrina and Michel approached me about the project because I liked the idea of telling these old stories in a new way and getting more people interested in these old myths,” he said.

School days

Like most Romansh cultural projects, Il Crestomat receives cantonal subsidies and funding from various foundations, including Lia Rumantscha, an umbrella organisation which works to maintain and promote Romansh.

“You can make whatever Romansh products you want – CDs, books, whatever – but you can’t finance them just by selling them. It’s not possible. We’re too small a community,” Decurtins says.

Daniel Telli from Lia Rumantscha thinks Il Crestomat is a “great idea because … these things are very interesting but they tend to be forgotten. The original Chresthomathie is about 12 volumes, which obviously you can’t carry around,” he tells swissinfo.ch at the organisation’s headquarters in Chur.

More

Minorities make themselves seen and heard

A variety of efforts are being undertaken to halt the gradual dwindling of Romansh speakers. Reasons for this decline include shifting demographics, limited demand from new arrivals and even peer pressure.

“When I was young, it wasn’t cool to speak Romansh. I went to Romansh kindergarten and then I went to primary school – this would have been at the end of the 1980s – and all the other kids were speaking German. It wasn’t cool to be in the small group speaking Romansh,” Durisch says.

“But then it turns around, so when you are about 18 you have this secret language that no one understands! For example, it’s perfect when you’re in Zurich and you want to speak about someone nearby – speak Romansh and no one can understand! Most of the time…”

Telli has also noticed changes. “When I was at school, we’d also speak Romansh with each other outside school, when we’d play football and so on. That is no longer the case – now they often speak German.”

Pass it on

So in addition to e-comics, what can be done? “The main thing is to convince everyone who speaks Romansh to pass it on to the next generation. Parents who speak Romansh should try to speak it to their children,” Telli says.

“This might sound banal, but I know cases where this doesn’t happen, for various reasons. Often when the mother is a German speaker it’s harder to hand the language down to the next generation. If this doesn’t happen, there’s a broken link and it’s harder to get reacquainted with the language later. These kids will then later say it’s such a pity their parents didn’t speak Romansh with them.”

This is the case with Durisch and his young daughter, who is not learning Romansh.

“Her mother is from Zurich and she speaks Swiss-German, so it’s difficult to get my daughter to say ‘dray’ [Romansh for three] instead of ‘druu’ [Swiss German]. And it’s nearly impossible for me to teach Romansh,” he says.

Despite the statistics, Telli says he is optimistic. “I know there are quite enough families with children who will be handing down the language. I think it will survive for many years to come.”

Michel Decurtins is slightly more circumspect. “Look, every language is dying – nobody speaks Latin anymore, one day in the distant future no one will speak English or Mandarin. And Romansh will also die, sure. But we don’t want the culture to die as fast as it looked as though it was dying 100 years ago,” he says.

“My father grew up knowing fewer Romansh words than I know, so some good stuff has happened, and if we keep that up, we can preserve some of our culture a bit longer.”

Romansh, spoken in the south-eastern canton of Graubünden, is descended from Latin, the common parent of all the Romance languages.

The most widely spoken are Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian and Romanian. Smaller Romance languages include Catalan, Galician, Lombard, Piedmontese, Napolitan, Sardinian, Occitan and Corsican.

Romansh is spoken in a number of different areas in the southeastern canton of Graubünden. Its nearest relatives outside Switzerland are Friulian and Ladin (spoken in northeastern Italy).

Romansh is divided into five written dialects or “idioms”, each with its own sub-dialects. The first written documents were produced in the Engadine in the 16th century.

Romansh has been recognised as a Swiss national language since 1938. Since 1996, the official administrative form of Romansh has been an artificially created version, Rumantsch Grischun, which has been in existence since 1980. The idiom with the greatest number of speakers is Sursilvan, spoken in the area along the Anterior Rhine (Vorderrhein) from its source near the Oberalp pass.

According to Lia Rumantscha, around 60,000 people can hold a conversation in Romansh.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.