The man from Shanghai: Marco Müller keeps sowing the future of cinema

After decades fostering generations of filmmakers worldwide, the former director of Locarno Film Festival is now nurturing the new generation of Chinese cinema - a generation that may soon turn China into the largest film industry in the world.

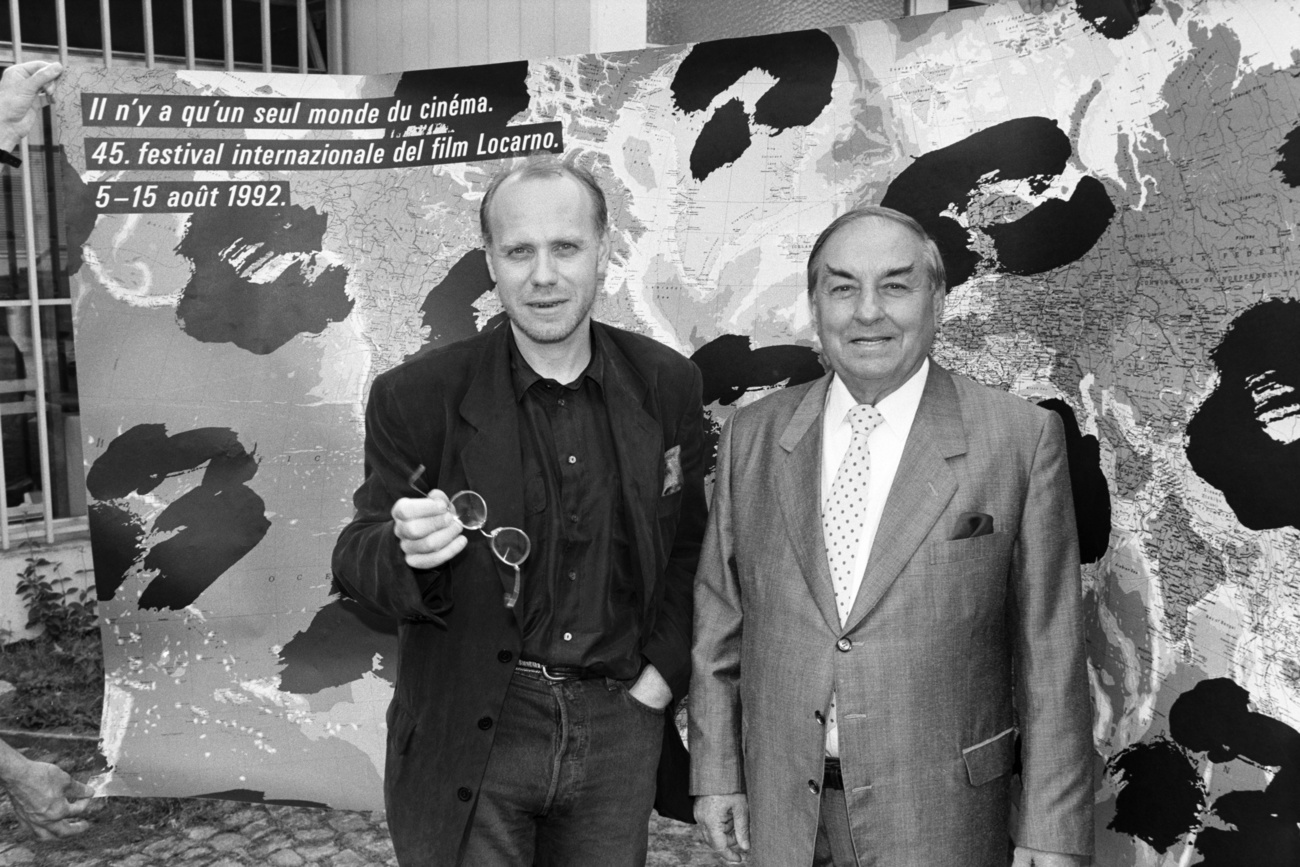

It’s not hard to find Marco Müller during Locarno Film Festival. This Italian with Swiss-Brazilian roots, who directed several festivals such as Rotterdam and Venice, spends his days and nights watching the Retrospective section, which has been a major highlight of Locarno since before his tenure (1992-2000), and this year brings 40 gems from the glorious days of Columbia Pictures.

Müller, 71, came to Locarno as a visiting spectator from China, where he has been living permanently for over five years. His mission there, as initially stated by the Propaganda Minister of the Municipal Committee of Shanghai in 2014, was to create the biggest film festival in the world. “They said, if Toronto has 300 films, let’s show 400 in nine days”, he tells SWI swissinfo.ch between sessions. “But my idea of karma is that you should not offer more than 60 or 70 features, apart from the retrospectives. You cannot show too many things.”

This modest scale may sound at odds with the ambitions of the second-largest film market in the world. Last year the Chinese box officeExternal link grossed $7.73 billion (CHF6.73 billion) from 1.3 billion admissions; in comparison, US figures in the same period topped $9 billion for 240 million spectators. Chinese-made films accounted for 84% of the total, and attendance to foreign films hasn’t changed since 2022.

Müller, though, is not concerned with box office numbers or with the evolving tastes of Chinese audiences. He is a coach-cum-producer by vocation, more in a league of world-class football coaches such as Pep Guardiola or José Mourinho than with any other of his peers in the film business. His initiatives were awarded in Cannes, Venice, Berlin, even with an Oscar (for best foreign film with No Man’s Land, 2001). “I’m really happy there because I learned how to be a producer again, using the money that can be found in China”, he says.

Marco Polo

Müller was one of the first Italian scholars to go study in China after the two countries normalised relations in the early 1970s, right in the wake of the Cultural Revolution. The then anthropology student started attending screenings of Chinese films with his classmates, some of whom would eventually become worldwide sensations – thanks in large part to Müller’s effort.

In the 1980s, he organised the first and most comprehensive events of Chinese cinema in the West, where names like Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige, and Wu Tianming – all Müller’s old mates – by the 1990s were already currency among filmgoers.

His return to China began gradually in 2014, having become definitive in 2021, when he was appointed artistic director of the Film Arts Research Centre at Shanghai University and Emeritus Professor at Shanghai Film Academy. He was previously festival director at China’s Pingyao International Film Festival and, more recently, founded the Asia-Europe Young Cinema Festival in Macau.

This year he has also been appointed artistic director of the Taormina Film FestivalExternal link, in Sicily, keeping a foot in Europe after cutting his last formal ties when he left his teaching position at the Academy of Architecture of the Università della Svizzera Italiana, in Mendrisio, in 2019.

More than collecting prestigious appointments, this extensive network serves Müller’s mission of connecting film professionals from the global East to West to South. Film festivals are above all a marketplace ecosystem where producers, distributors, sales agents, and buyers converge, and the Coach knows very well how to navigate among all of them.

In favour of the young

Müller seems impervious to the constraints of working within a heavily state-controlled film industry as China’s. “You have to find a way to work with them. Mine was that I’ve always took a stand in favour of the new indie filmmakers and producers in China, and that was possible”, he says.

In January, he staged the first edition of the Asia-Europe Young Cinema Festival in Macau. As Müller explains, the ‘Asia-Europe’ label has a subtle geopolitical significance. “It’s not that I didn’t want to please the government, but if I used the official labels like ‘Silk Road’ or ‘BRICS’, there would be a lot of resistance [abroad]. In a way I reversed the Russian traditional concept of Eurasia when I say Asia-Europe. And it worked”.

The former Portuguese colony’s devolution deal, effective when the Portuguese left in 1999, also offers a special openness in comparison to the rest of the country. “In Macau, I made a programme specific for new filmmakers from China, be they members of the China Film Directors Association or not, so that they could meet with filmmakers from abroad and see the films that officially cannot be seen.”

“Through Macau, as it was possible in the past through Hong Kong, you can also find Chinese private funds for prestige projects created even by new directors”, says Müller. “In this sense, the most important thing,” he adds, “is our Work-in-Progress Lab, with 16 works-in-progress being shown to all the important festivals in the world. As these films are getting completed, they are going to San Sebastian, Berlin and hopefully Cannes [film festivals]next.”

For a handful of francs

Talking about China in a café in Locarno suddenly feels like discussing sci-fi movies. The realities of the film industry in China and in Switzerland couldn’t be more contrasting. While in China private funds are flowing and government commitment is plain to see, the talk of the town in Locarno during this festival is a drastic cut in Swiss federal funds for international cultural cooperation.

These funds are managed by the Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), a department of the foreign ministry, and were distributed according to a model that Müller started developing in Switzerland since the early 1990s. Its aim is to foster the development and production of artistic works by young talents in countries with struggling cultural (and film) industries.

In the first days of the festival, last week, a group of 12 Swiss cultural partners in the SDC framework published a statement decrying the slashing of the fund.

In absolute numbers, and considering the overall federal budget, it sounds like a pittance: a very modest CHF1.7 million ($2 million). But it represents a 45% cut in the budget for cultural production, and affects some programmes that have successfully raised Switzerland’s profile, like Locarno’s Open DoorsExternal link programme, and Zurich’s Theater SpektakelExternal link. For some others, like the platforms artlinkExternal link and Visions Sud EstExternal link, the cuts represent an existential threat.

“Things definitely have changed here”, says Müller, as he recalls the evolution of an idea he began developing far back in the days.

“In fact, the idea was very simple”, says Müller. “If we could raise 300 from private investors, the SDC would give us 300, and so on. It really helped me to be very considerate about spending that money.” So he established the Fondazione Monte Cinema Verità and created a committee of experts in production and funding, including one person from Swiss public television.

Killing the golden goose?

Swiss producers subsequently started to co-produce films from the global South and the East. “The fact that the SDC forced us to have private partners was a very healthy thing, in the sense that it really spurred us to continue taking responsibility for each and every project.”

The model then started to be copied by other institutions dealing not just with film but also with theater, fine arts, and literature.

Visions Sud Est External linkinherited the modus operandi of Müller’s Fondazione when the latter ceased its activities in 2004 and is one of the cultural bodies whose existence is threatened by the recent SDC cuts.

Even small amounts (to the order of CHF20,000 to CHF50,000) raised by the agency get doubled with the SDC contribution, and that means a decent seed capital to develop a film, especially in projects that, as Müller describes, “nobody else dares to fund, or that could not be funded in the country of origin because the filmmakers wanted to speak certain uncomfortable or censored truths”.

Müller can only lament from afar as he watches the model he created being dismantled. “But I think that the private sector should take a stand. For over 20 years, private investors have been part of the fund, so they should also voice their disappointment with these cuts.”

Müller looks at his watch, the next screening of the Retrospective is about to start. The Coach tries to summarise his thoughts. “The story I’m telling you is related to individual efforts and to that period in time when Switzerland could afford to offer the space for international workshops. But even if the times have changed, I really can see no reason why we should discontinue this successful model.”

Edited by Mark Livingston/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.