The new director of Zurich’s Fine Arts Museum is not afraid to fail

A breath of fresh air blew into one of Zurich’s oldest cultural institutions this year as Belgian curator Ann Demeester takes over the artistic direction of the Kunsthaus, the Museum of Fine Arts. SWI swissinfo.ch met her to discuss her vision for the historic art institution.

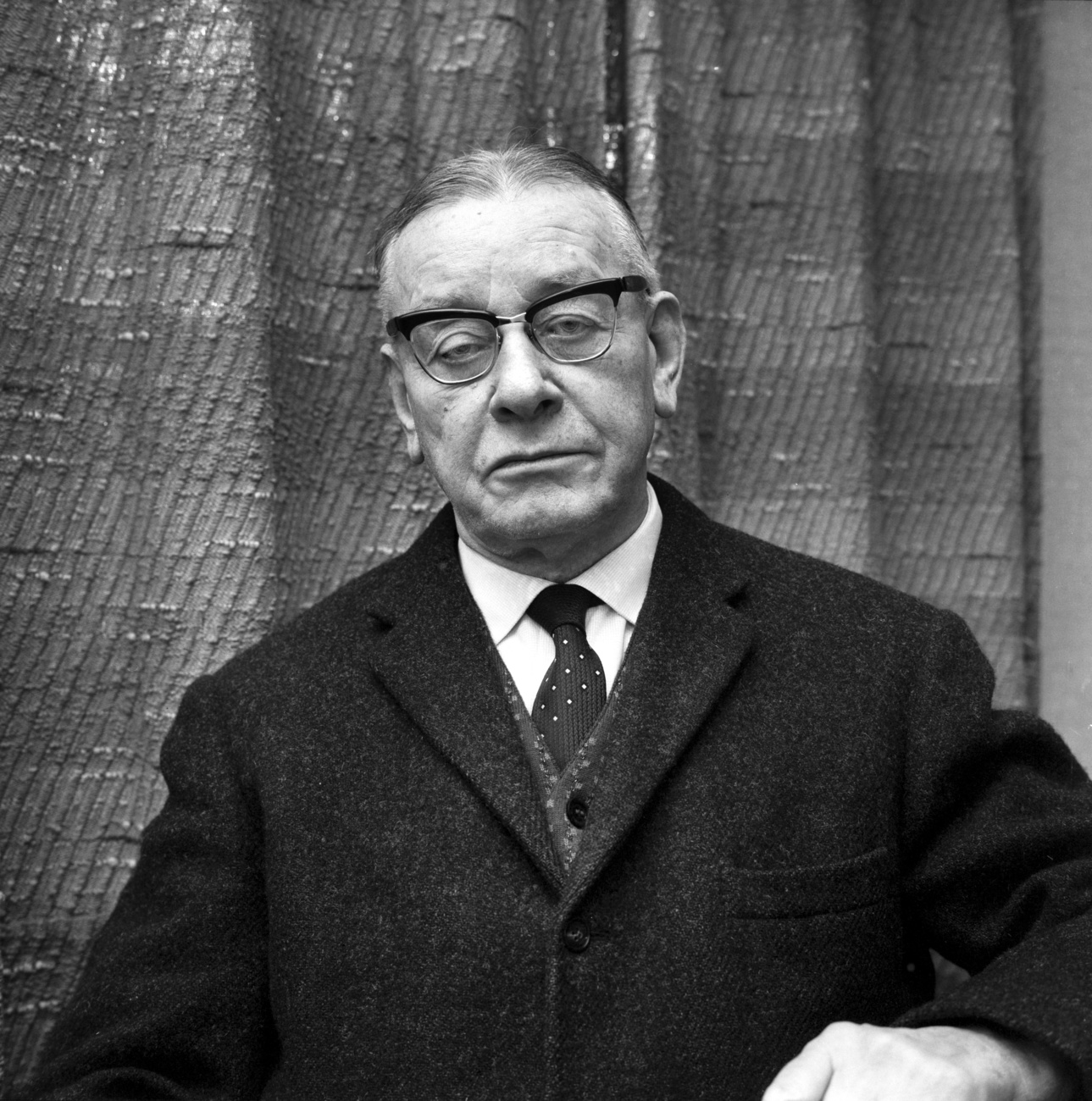

Christoph Becker’s more than 20-year tenure as director of the Zürich Fine Arts Museum should have ended in triumph, with the opening of a huge extension by star architect David Chipperfield in October 2021 making it the largest Swiss art museum. His final exhibition, a solo presentation of French artist Niki de Saint Phalle’s work, currently on view, was a counterweight to a programme in which male artists grabbed most attention.

Yet, since last year, the headlines for the Zürich museum – a private institution held by an association of 25,000 members – have clouded his legacy. The new extension was built to house, amongst other prominent collections, some 200 predominantly Impressionist artworks loaned by the Bührle Collection. This had been assembled by Emil Georg Bührle, who became rich selling arms to Germany during World War II and bought some art that was either looted by the Nazis or sold by Jewish owners under duress.

Since then, Zürich’s most prestigious, and expensive, fine arts museum has been under fire for not meeting the transparency standards demanded by historians and specialists. Despite the scandal, the collection is still on show.

That’s the tense situation the new director inherits. Ann Demeester comes to Zürich from the Netherlands, where she was latterly director of the Frans Hals Museums in Haarlem, having started her career in arts journalism before moving into curating. Her work is known for audacious curation that allows art across epochs and disciplines to meet and confront each other.

Following a gradual handover, Demeester officially becomes Zürich’s fine arts museum director on October 1, 2022. Hopes are high that the new head of the institution will revive its reputation.

SWI: You have been involved in the daily work of the museum over the last months. What was your perception of the institution before moving to Zurich?

AD: It’s a gigantic museum with a remarkable collection, but doesn’t have the visibility of other flagships like the Musée d’Orsay (Paris) or Tate Britain. It retained a sense of adventure and discovery.

SWI: What are the challenges of the role?

A.D: One challenge is to activate the huge collection that spans many centuries and with which people are less familiar.

The other challenge is how we can be both a Bilderpalast – a palace of images where you marvel at and maybe worship art – and at the same time be a contemporary response to an increasingly fluid and complex world where you cannot escape social, political questions and how they intertwine with art, be that historic or contemporary.

I don’t believe in the split between history and art history. History is in embedded in history of art; social context is always present, even in old masterpieces.

Before the museum as we know it was created, we had cabinets of curiosities. These were a wild assembly of heterogenous objects and ideas, of flora and fauna, of art, etching and books; where everything was about marvel.

Then came the museum, which was more didactic and used categories from art history [to organize content]. It didn’t include the perspective of artists on art history, which is not necessarily linear and chronological. Curating a museum for me is about imaginative associations or affinities between things that don’t necessarily belong in the same category.

We live in a networked society and if we want to be relevant and contemporary, we should also make connections between art across different periods of history.

SWI: The last few years have been turbulent for the museum. Most prominent has been criticism of the display and the loan conditions of the Bührle Collection. How does the museum address questions of provenance now?

A.D: The discussion around Bührle has many different angles. Provenance is one of them and a vital one. But the topic is also a pars pro toto, part of a larger discussion, on how Switzerland is dealing with its role in the Second World War. It is about sourcing funds, too.

That’s a really big issue for any museum in Europe: where does our money come from; who are we dependent on? Money from Sackler (the family behind an opioid scandal in the United States) and BP (the British multinational oil and gas company) is no longer acceptable. How do we deal with that ethically and remain in tune with our times?

SWI: Will loans or bequests be handled in a transparent fashion in the future?

A.D: Negotiations cannot be held in the open, that’s also true when they concern loans or bequests. But we need to recalibrate our principles. What do we accept, when, why and for what reason? Those are the questions a museum should be asking itself every 20 years anyhow.

It’s part of institutional hygiene. We have to do this with more vulnerability and transparency.

SWI: The feminist collective Hulda Zwingli is critical that the art exhibited here is overwhelmingly male. Is that going to change?

AD: Yes and no. The museum has a certain reputation while the reality is not as stark. We can make historical gaps visible, but we cannot fill them. I don’t think I’ll find funds to buy more works by Mary Cassatt or Sonja Sekulas, two female artists of the last century. But we can change the future.

I’ve always, together with a team, compiled a programme that found a fair balance between male and female. Maybe we are not always entirely ‘global’: we’re very Euro-American. That’s a more valid charge against the museum. Can we change that, and should we? Why would we in the West have to represent and own the entire world? It’s a dangerous thought. Maybe that is another form of cultural neo-colonialism.

SWI: What is the role of a fine art museum today?

A.D: A centre of curiosity. Fine art is anachronistic, it’s too slow to respond to the fluidity of the world today. What we can do as a museum is stimulate curiosity on all possible levels through art.

At the end of the 1960s the American conceptual artist James Lee Byars created a performance (The World Question Centre) in which he asked everyone he deemed important in the world – intellectually, politically, scientifically, economically – to ask him what they perceived as “the most relevant question right now”. Not to give answers, but questions. The museum should be that.

We should also still be that palace where art is revered, but also a palace where we can re-charge art with new ideas and inspiration. We should ask questions through the perspectives of artists. We should also be a parliament where ideas are discussed.

The big dilemma is how to be hybrid – not just ‘either or’. How this is done depends upon the culture of debate in the country. We have to identify how we can have those discussions in combination with each other in Zurich. That we have to do it, is undisputable, but the format is still unclear.

More

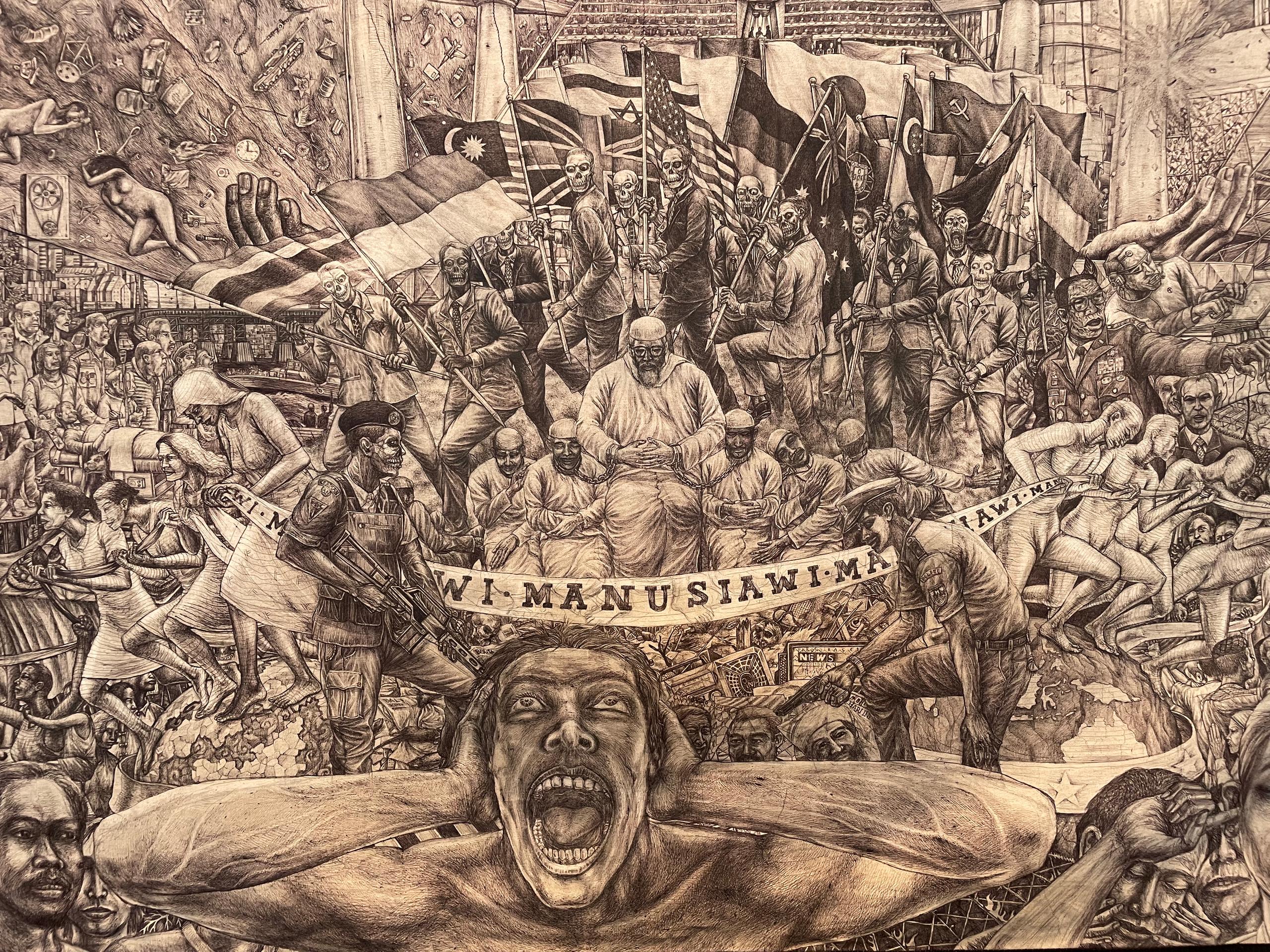

The South goes North: documenta15 turns the art world upside down

SWI: The headline contemporary art exhibitions this last summer, documenta 15 in Kassel and the Berlin Biennial, both tried to be socially relevant spaces – and were – but both were also problematic. For example, some Iraqi artists withdrew from the Berlin exhibition, because it included images of torture from the public domain. In Kassel, sharing the curation with a multitude of collective groups did indeed bring about a loss of central control.

A.D: You have to accept that if you try to create these spaces there will be some failure involved. What I regret about documenta is that the discussion about antisemitism is all we read in the media. It is a vital, essential discussion, there’s no doubt about that.

But documenta also proposed something radically different about the collective way of working: art is not about the art object, it’s about the process, about how to work together. It’s a paradigm change that is trying to make art inclusive and democratic. But the regular visitors seem often at a loss. What is meant to be really democratic is actually exclusive, because people’s understanding of art is more traditional.

We’re used to doing things the right way, but the biggest mindset change is how to allow ourselves to fail! The common understanding of what a museum is in Europe is not this democratic polyphonic space of ambiguity and paradox and discussion – it’s a place you walk into and look at objects you can identify as art.

SWI: So how do you introduce that novel agenda?

A.D: You have to offer tradition and to bring in critical questioning at the same time. We can’t keep on sanitising art and putting it in a vacuum as if it has nothing to do with the problems of our day. It’s the opposite of choosing the road less travelled, it’s travelling two paths simultaneously.

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.