The “Prisoner of Chillon” lives on

Chillon near Montreux is one of the best-known castles in Europe. Situated on a rocky islet just off Lake Geneva's shore, it has for centuries inspired nobility and artists alike.

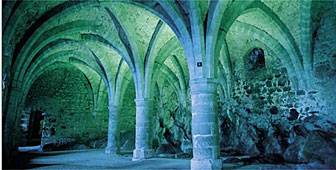

From the courtyard near the gate, stone steps lead down to the prison and gallows. High gothic arches support the ceiling of the cellar and upper floors. Waves lap against the outside walls and can be heard through the entrances that open on to the lake.

Guide Graziella Toukabri points to the gallows. “It’s not the original one. The original wasn’t placed as high but if we put it where it used to be than everybody would want to try it, and then we’d have to replace it everyday,” she laughs. Hers is a peculiar kind of gallows humour.

When the gallows were in use, the bodies of their victims would be thrown into the lake. In fact, says Toukabri, the keepers of the castle used to throw everything into the lake. Another laugh.

Toukabri steps through a narrow door into the next part of the cellar, which has been known as “Bonivard’s Prison” since Byron wrote “The Prisoner of Chillon” in 1816.

“There are seven pillars of Gothic mould,

In Chillon’s dungeons deep and old…

They chain’d us each to a column stone,

And we were three – yet each alone,

We could not move a single pace,

We could not see each other’s face…”

The poet, on a boat tour around Lake Geneva, was forced to take shelter at Montreux during a storm. He was given a tour of the castle and was told the story of its most famous prisoner, Bonivard – a leading 16th century Protestant clergyman who was imprisoned there by the Catholic counts of Savoy.

The tourist brochure states that Bonivard was “chained for four years to the fifth pillar”.

“Actually we don’t know if that’s true because it was Lord Byron who wrote that Bonivard was chained to the fifth pillar,” Toukabri explains. “He was a prisoner in the Chillon castle but he lived in the governor’s chambers.

“It was only during the last six months when the count found out that he was living with the governor that he was placed in the dungeon. But tourists are disappointed if we tell them he only spent six months in the dungeon. So we have to say that he was standing there for four years.”

Tourists also believe they can see footprints left by Bonivard, whose freedom of movement was limited to the length of his chain.

“Bonivard was here between 1532 and 1536, Lord Byron wrote the poem in 1816, and we’re now in the 21st century,” says Toukabri. “About 300,000 people visit the castle each year, so it’s stretching the truth if we say that we can still see the footprints of Bonivard.”

Bonivard was freed by the Bernese, who wrested control of the region from the Counts of Savoy. The new masters also ended Chillon’s days as a governor’s residence and stronghold on the main route over the Alps between Geneva and Italy.

The Bernese let the fortress fall into disrepair, using many of its grand halls and chambers for storage. It only regained its medieval splendour after renovations were carried out in the first half of the 20th century.

Visitors can now see the original arched wooden ceilings – the boards of which were once held together by gold nails – and their massive oak pillars and secret passageways leading into bedchambers.

It’s possible to imagine how young men used to row their boats up to the castle walls, and serenade the single women peering out the windows enjoying the magnificent views over the lake and mountains.

But it’s the dungeons below, thanks to Byron’s story of Bonivard, that make Chillon such a fascinating place:

“I only lived, I only drew

The accursed breath of dungeon-dew…”

by Dale Bechtel

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.