The secret of immortality? For Swiss artist Dieter Roth, ‘organic irreverence’

June 5 marks the 25th anniversary of Dieter Roth’s death. The artist left not only an enormous body of work but a reminder of what is at the heart of art: a free spirit, creative chaos, an uncompromising attitude and, above all, an anarchic sense of humour.

Exactly 25 years ago Dieter Roth had a fatal heart attack aged 68 in his studio in Basel. For such a tireless, relentless artist, only death could make him stop working.

Roth’s legacy, however, lies not only in the numerous artworks he left, but also in his attitude to life and the arts that seem so at odds with the art scene of today.

The polymath artist combined a frantic, industrious productivity with an attitude of absolute irreverence. For Roth, nothing was sacred – and even less the canons of art. Everything that came his way was an opportunity to reinterpret, reassemble, invert, exploit or pun. That included his own name: born Karl-Dietrich Roth, he also signed under the aliases Dieter Rot and Diter Rot, revelling in the double meaning of the English “rot”, “rotten” and the German for “red”.

Roth left an incredible body of work virtually impossible to categorise. In the mid-1970s, for instance, the German publisher Hansjörg Mayer convinced him to put together what he called his “bookworks”, in which Roth re-invented the medium in different ways for different uses (and hardly ever for reading).

The resulting Gesammelte Werke (collected works) run to 26 volumes. But the “bookworks” were just one of his series. Cataloguing the whole range of sculptures, prints, paintings, postcards, films and poetry is no easy feat.

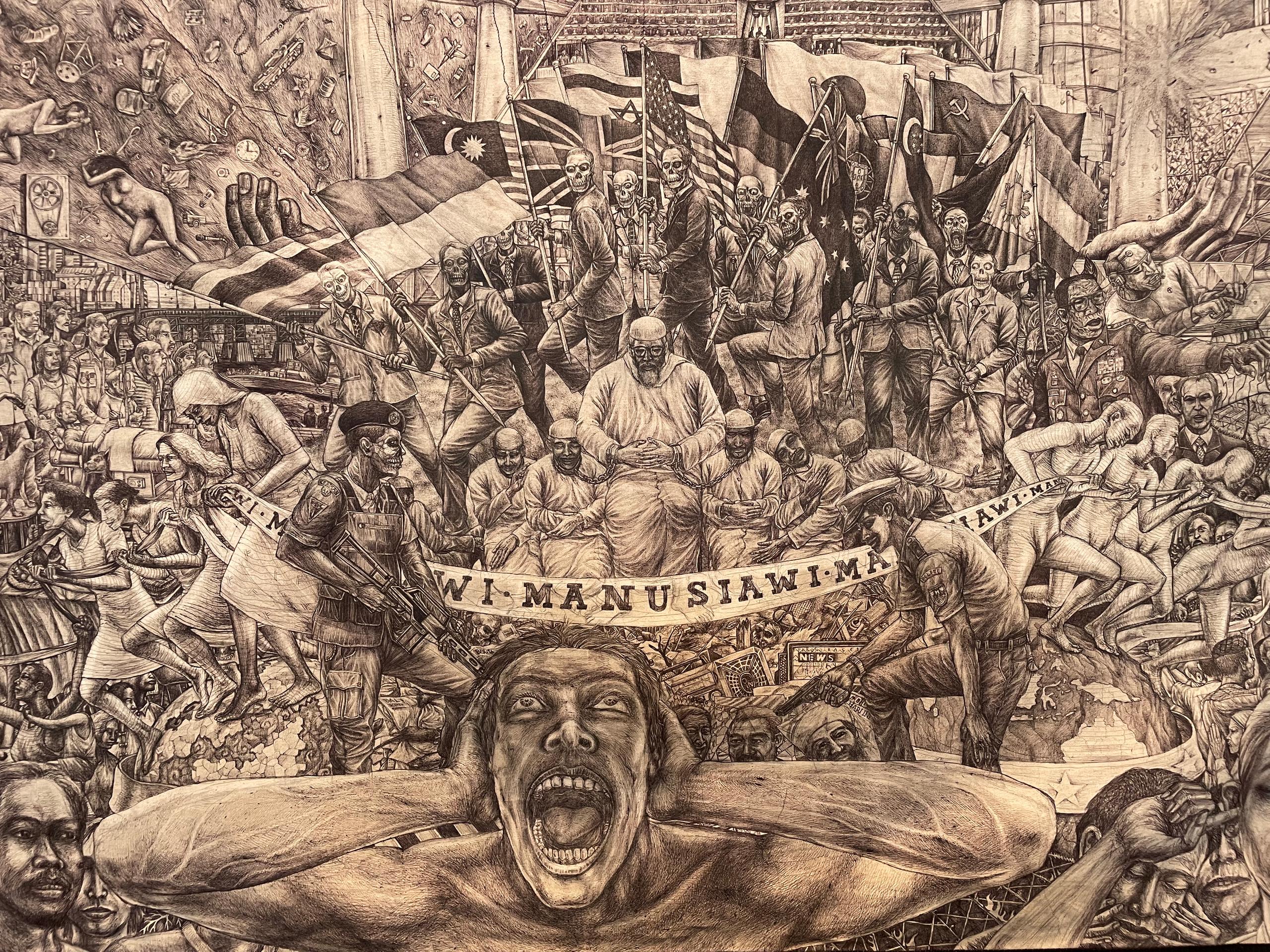

Everywhere man

Roth was born in the German city of Hanover in 1930 and in the first years of the Second World War (1939-45) he spent his summers in Switzerland: being a dual national (his father was Swiss, his mother German), he could take advantage of Swiss neutrality and be spared the carnage of the war.

After 1943, his exile became permanent, and he was hosted by a family who also sheltered Jewish and communist artists. This set-up certainly influenced the young refugee, who by the 1950s had already quit his original job in advertising for the itinerant and bohemian universe of the contemporary avant-garde.

From then on, Roth’s nomadic life led him to the epicentres of the European and Western art scenes in the second half of the 20th century. Essentially a loner, Roth never engaged with or joined any group or movement, even though he befriended almost everyone who made a splash: the circle of angry young German artists of the 1960s such as Joseph Beuys, Daniel Spoerri and Sigmar Polke; the global Fluxus group; pop artists, or neo-Dadaists.

In the 1960s, during the early years of the documentaExternal link exhibitions in Kassel, today the most important art show in Europe and beyond, Roth’s limited editions of signed prints sparked a democratisation in art collecting. The then burgeoning middle class could acquire affordable artworks sold in documenta’s shop – initiating a commercial trend that continues to boost the revenues of art shows, museums and galleries all over the world (documenta cut off all its commercial actions after a major revamp in 1972).

Roth’s inventiveness was tireless: he transformed literature into a sausage (literally). He invented his own method of “biodegradable art”, using organic materials such as yoghurt, chocolate, banana and cheese, and then the fungus and dead flies produced by the rot. He used his American students, who had poor German, to typeset his book of poems, Scheisse. Neue Gedichte von Dieter Rot (Shit. New Poems by Dieter Rot), and included all their misspellings and errors.

Roth didn’t invent the “multiples” (a series of identical artworks, usually a signed limited edition made specifically for selling), but he stood apart from his most radical contemporaries with his little sculptures made of chocolate and cake (which obviously haven’t survived). He even cast little bunnies in the famous Lindt & Sprüngli mould but instead of chocolate, he used rabbit faeces.

Even if Roth’s name and fame hasn’t made him a commonplace entity among his equals, such as Beuys or Yoko Ono, his works are still circulating in the art market. Many of his prints and multiples are quite affordable at $400-$10,000 (CHF360-CHF9,110), while more pricey pieces reach the six digits and circulate around higher-end auction houses and galleries.

The Hauser & Wirth gallery in the Swiss mountain resort of St Moritz is exhibiting Roth’s only installation currently on show. The Roth BarExternal link, made with his son and long-time collaborator Björn, has literally outlived its maker and continues to evolve and grow.

Immortal anecdotes

The outstanding body of work left by Roth competes with his immaterial legacy, carried on by a community of fans, friends, former collaborators, colleagues and fellow artists who founded a Dieter Roth AcademyExternal link in 2000.

Faithful to the artist’s idea, developed in his later years, of an institution unbound to any particular place or curriculum, the Academy has no physical base and convenes with no regular schedule in different parts of the world, from Basel to Hungary, China and Germany.

Its website assembles thousands of articles, original texts, translations and materials not available anywhere else. Most remarkably, every “conference” of the academy invariably ends with participants telling their stories, anecdotes and jokes about Roth – a custom that has become a ritual.

In an age when artists are just a cog in a multibillion-dollar art market, where art schools offer masters and doctorate degrees, and artworks have incorporated scientific research and methods, Roth’s stance of experimentation and irreverence, for their own sakes, is a drunken, sobering counter-model.

With input from Caroline Honegger (archives). Edited by Virginie Mangin.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.