The Swiss film harvest for 2024: taking stock of migration and the right to protest

The 59th Solothurn Film Festival, a showcase of the most recent Swiss productions, highlights the hot topics immigration and the curbs on transgressive protest. Will Switzerland heed the call?

If one wanted to provide evidence for the claim that a national film culture reflects, in broad strokes, the mood of the respective nation, one could hardly find a handier case study than Switzerland.

Not only are large portions of the country’s cinematic output funded at least in part by state bodies, meaning that filmmakers are incentivised to tackle issues generally deemed to be currently relevant – the Swiss film calendar also conveniently sets aside one week each year where most of this output is screened alongside one another, facilitating any attempt at making sense of what is on Switzerland’s cultural mind.

The week in question is the Solothurn Film Festival, which takes place every January in the small town of Solothurn in northwestern Switzerland, and whose focus lies squarely on Swiss films produced over the course of the preceding twelve months.

Swiss collective imagination

On January 24, the festival’s 59th edition wrapped, and both the winners of its most coveted prizes and the themes emerging from its broader, typically documentary-heavy programming do go a long way in deducing what topics and narratives are swirling around Switzerland’s collective imagination.

Indeed, perhaps the most intriguing conclusion to be drawn from this year’s festival is that Swiss cinema seems to be engaged in a struggle to make sense of two distinct but ultimately interrelated discourses that animate the polar ends of the political spectrum – the country’s restrictive approach to all things immigration on the one hand and the question of where to draw the line between legitimate and illegitimate forms of political dissent on the other.

Take the documentary which took home the Prix de Soleure, the festival’s top prize: Lisa Gerig’s The Hearing (Die Anhörung) stars real asylum applicants – a young man from war-torn Afghanistan, a former indentured servant from Nigeria, a persecuted political activist from Cameroon, and a trans woman and prominent campaigner for LGBTQ+ rights in Sri Lanka – going through a simulated asylum application hearing and telling their actual life stories to real case workers from Switzerland’s State Secretariat for Migration (SEM).

Gerig may overplay her hand in places, occasionally mining the concept’s inherent absurdity more for laughs than genuine insight. Yet on the whole, The Hearing is an appropriately thorny effort to make tangible the indignity of current SEM protocol, which, it transpires, is designed to reward applicants’ storytelling prowess and to punish their reluctance to relive certain traumatic experiences in a semi-public setting.

In a striking third-act pivot – a literal turning of the interrogation room table – the film even puts representatives of the Swiss immigration system on symbolic trial by having the immigrant protagonists interview them about why they work in support of the draconian system as it exists now, using a SEM-style line of questioning.

What The Hearing leaves its audience with is both a feeling of righteous anger at the apparent heartlessness and arbitrariness of a major government institution and an arguably even more troubling sense of appreciation for the degree to which immigrant life in Switzerland is shaped by the public’s demand for performing the role of “the good refugee.”

Real citizens

This dynamic is also at play in Luka Popadić’s My Swiss Army, whose original German title – Echte Schweizer (“Real Swiss”) – is a good deal more suggestive. The documentary, which won Solothurn’s other top prize, the audience award, explores the multicultural, multi-ethnic slice of Switzerland’s armed forces through its portrait of a handful of military officers of Serbian, Tunisian, and Sri Lankan extraction (including the director himself) – raising questions about heritage and belonging and perpetuating the image of the army as an agent of integration.

Yet the theme was also prevalent outside the list of winners. Mehdi Sahebi’s Prisoners of Fate (see trailer above – in Farsi, with German and French subtitles) accompanies various Iranian asylum applicants over the course of several years as they struggle to navigate both their uncertain immigration status and life in Switzerland.

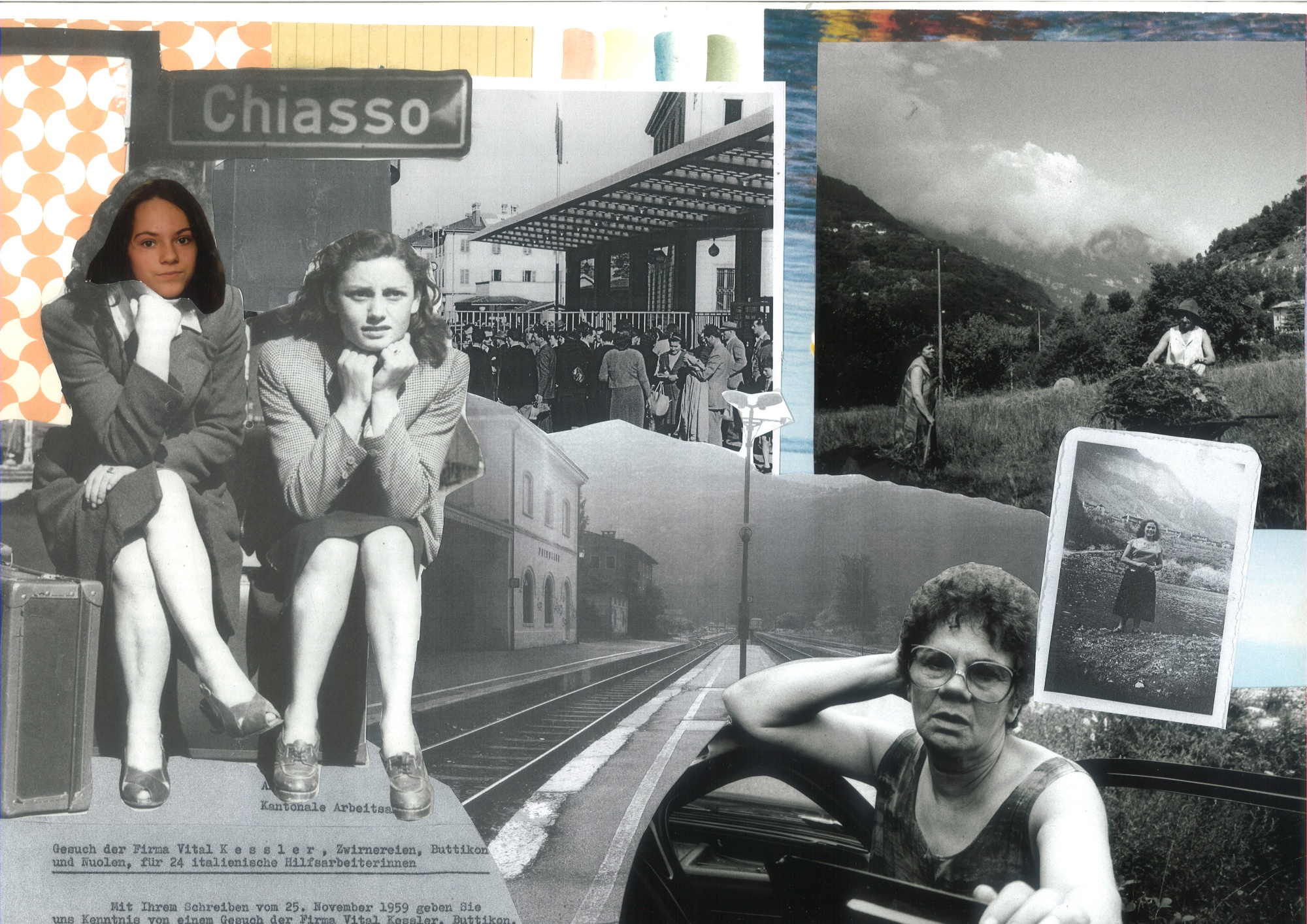

In Motherland (Mutterland), director Miriam Pucitta reflects on her family’s life as Italian guest workers in 1960s and 1970s Switzerland. Even Omegäng, Aldo Gugolz’s affable investigation into the state of the Swiss-German language, touches on issues of migration, featuring scenes of immigrant workers being taught the arcane dialect of the canton of Uri, so they are able to assimilate into the village community more easily.

Hard times to be a rebel

Complementing this pervasive presence of migration as a topic of conversation, the Solothurn line-up also included its share of films tackling the history and the current state of transgressive political activism in Switzerland – especially of the left-wing, anti-racist, anti-xenophobic variety.

This, too, is reflected in the festival’s choice of winners: About Fire (Autour du feu) by Laura Cazador and Amanda Cortés, which was awarded the jury prize for best first or second feature, sees veterans of the armed anti-capitalist Fasel Gang, which was active in Switzerland between 1977 and 1991, engage in a fireside chat with representatives from various present-day activist groups, including the environmental movement Extinction Rebellion and several anti-racist collectives.

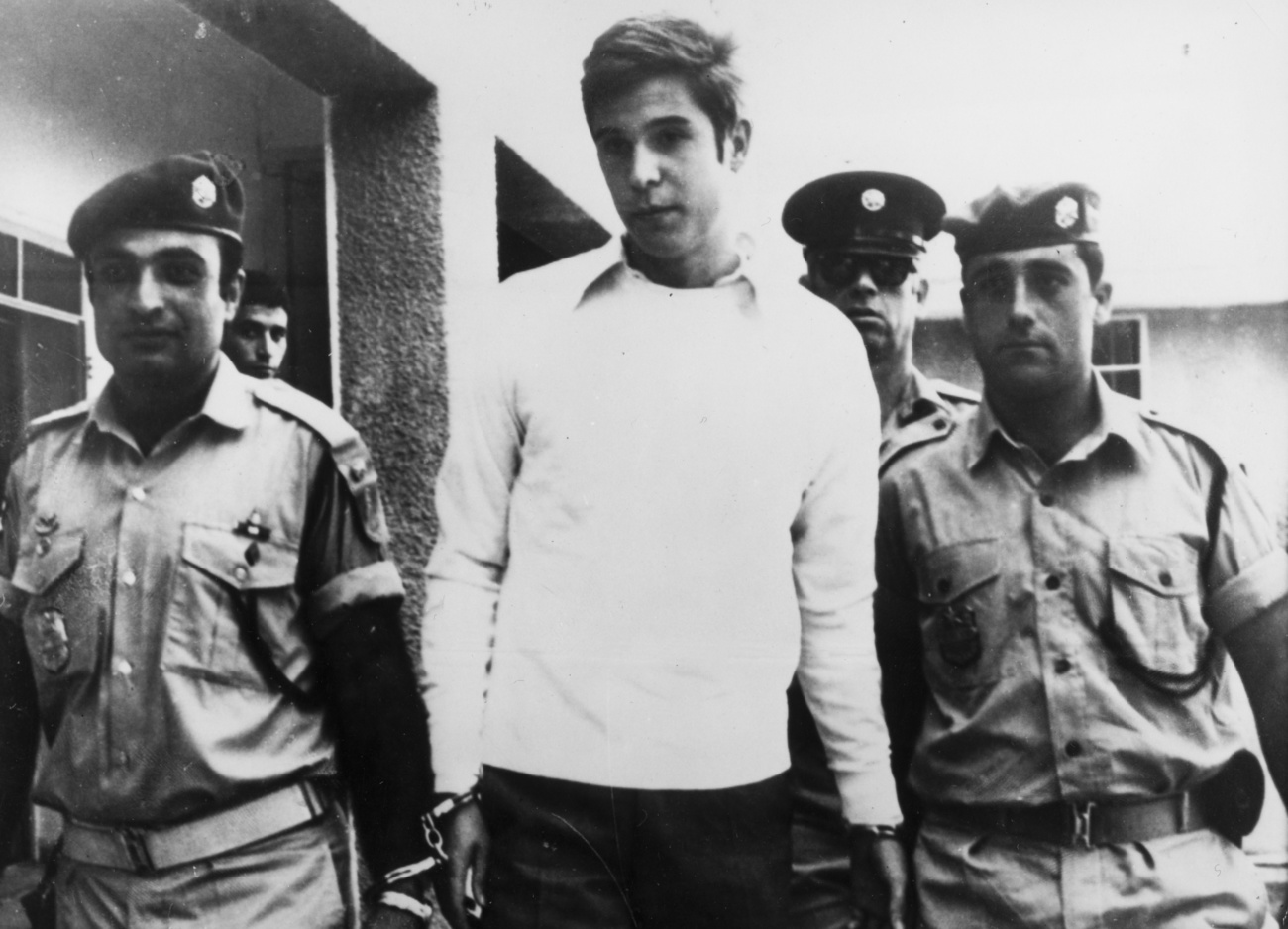

The issues raised by Cazador and Cortés’ documentary – the rationale behind disruptive activism, the changes in the political landscape, the guardrails put in place by the state, by public opinion, and by oneself – are made even more explicit in La scomparsa di Bruno Breguet (“The disappearance of Bruno Breguet”).

Olmo Cerri’s portrait of the once-controversial, now-forgotten far-left Swiss “terrorist” Bruno Breguet is interspersed with the pacifist Cerri’s musings about how likening street blockades staged by climate activists to terrorism is akin to delegitimising all forms of progressive protest.

However, if Solothurn is a chance to take Switzerland’s cultural temperature, it is also necessary to acknowledge that it, as an elite institution dealing in narrative art, is not the place in which to look for solutions to the problems and conditions its programme highlights.

For all the well-intentioned work of films like The Hearing, My Swiss Army, and About Fire, one must resist the temptation to equate their efforts to engage in difficult conversations – and their awards success – with Switzerland writ large doing the same.

The prizes have been handed out, the spotlights of the festival and its marquee films have faded – yet the Swiss asylum application process remains a bureaucratic nightmare for many, and the public discourse about acceptable forms of protest remains dangerously fraught. Solothurn has set the template for a national dialogue, but will the rest of the country follow suit?

Edited by Eduardo Simantob and Virginie Mangin/ac

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.