Poor, cold and rebellious: the Swiss Jura shows its rich imagination in films

In its 60th edition, the Solothurn Film Festival used its retrospective to highlight films about the Jura region – a place of Swiss separatism, linguistic divides, economic hardship, and nostalgia.

Geographically, Switzerland can be divided into three main sections. There are the Alps, evoking the past: William Tell, rugged Alpine herdsmen and Switzerland’s history as a hermit confederacy resisting the tides of European history in its stony fortress.

Then there’s the Swiss plateau. Stretching from Geneva in the southwest to St Gallen in the northeast, this is, despite its rolling green hills and farmlands, urban Switzerland – home to over two-thirds of the country’s population and almost all its major cities, metropolitan areas and industrial hubs. Whatever future Switzerland might be heading towards, few would disagree that it lies here.

Finally, straddling the border between Switzerland and France, there’s the Jura. A comparatively thin strip of low mountain terrain, 70% of which is located on French soil, it dominates significant parts of the landscape in the cantons of Vaud, Neuchâtel, Bern, Jura, Solothurn and Basel Country. And yet it seems to play a much smaller role in the Swiss imagination than either the Alps or the plateau.

Enter the Solothurn Film Festival, the annual showcase of the Swiss film industry, which took place for the 60th time from January 22-29. It marked the anniversary with a 30-film retrospective dedicated to the “Imaginaires du Jura” – the Jura as it exists in the pop-cultural archive of Swiss and French cinema. If the Alps are, in a sense, the past of Switzerland, and the plateau its present and future, what role is there for the Jura?

Arson and bombs

One of the most forceful answers to that question was to be found not in the retrospective, but in the festival’s features section. Pierre-Alain Meier’s 2024 documentary Sans Roland Béguelin et Marcel Boillat, pas de Canton du Jura! (“Without Roland Béguelin and Marcel Boillat, No Canton of Jura!”) chronicles the only major separatist movement in modern Swiss history, which gripped the French-speaking parts of canton Bern from 1947 onwards.

The movement’s radical wing inspired a much-publicised bombing and arson campaign in the 1960s and 1970s, that eventually led to the creation of canton Jura in 1978.

The reason for all of this, according to Meier’s collage of archival material, was not just the historical indignity of Jura having been annexed by Bern in 1815. Rather, it was the widespread feeling of not being accepted as an equal part of the population, the sense that the people of the Bernese Jura and their francophone cultural identities were seen by the German-speaking authorities as merely a roadblock on the way towards full assimilation.

What does the Jura stand for? In Meier’s telling – and in the separatist figurehead Roland Béguelin’s view – the region is a symbol for French-speaking resistance against the cultural, political, economic and linguistic dominance of all things Swiss German.

But the temperament of the Jura runs deeper than that: the region was also the cradle of Swiss watchmaking, producing since 1748 world-renowned brands, including Audemars Piguet, Jaeger-LeCoultre, and David Candaux. At the turn of the 20th century its workshops were hotbeds of anarchist activity which inspired revolutionary thinkers such as Peter Kropotkin (1842-1921) – and the recent film Unrest, by Cyril Schäublin (2022).

The ‘Wild West’ of Switzerland

This idea reverberated throughout the festival’s retrospective. Billed in the programme trailer as both the “Wild West” of Switzerland and as a “frontier zone”, the area is, in its cinematic incarnations, commonly used as a meeting place between the old and the new, between the familiar and the unknown, between the countryside and the city, and, yes, between French and German.

Take Gilberte de Courgenay, Franz Schnyder’s 1941 classic of Swiss Second World War cinema. An unapologetically sentimental and nostalgic piece of wartime propaganda, it revolves around a group of Swiss German-speaking First World War soldiers having to spend Christmas and New Year’s on border patrol duty in a small Jura village, where they collectively fall in love with Gilberte (Anne-Marie Blanc), the local barmaid.

Inspired by the real-life figure of Gilberte Montavon, Schnyder’s film pays patriotic homage to the soldiers protecting Swiss sovereignty and the women helping them cope with homesickness and reminding them to stay faithful to their sweethearts back home.

Here, the Jura gives the initially reluctant soldiers a glimpse of the wider world, with Gilberte playing the dual role of exotically French-accented distraction and level-headed corrective to the protagonists’ overzealous passions. In other words, Gilberte de Courgenay’s Jura is a place to visit, maybe even learn from, but certainly not one to stay in.

Hard life and murder mystery

Yet even when all the characters are Jura natives, the question of belonging is not a straightforward one. In Polish-Swiss director Greg Zglinski’s One Long Winter without Fire (Tout un hiver sans feu), which won the top prize at the 2005 Swiss Film Awards, the very possibility of carving out a living in the Jura Mountains, with their infamously freezing winters and perennially precarious economic prospects, is called into question.

Set in and around La Chaux-de-Fonds, the film tells the story of a struggling dairy farmer (Aurélien Recoing) who, after his wife is committed to a psychiatric institution, starts working in a factory, befriends a Kosovan colleague, and promptly falls in love with the man’s sister – before inevitably realising that this new life isn’t all it’s cracked up to be either.

It’s a dynamic that exists on the French side of the border as well, as seen in Jean Chapot’s atmospheric murder mystery The Burned Barns (Les Granges Brûlées) from 1973.

Starring acting titans Alain Delon as an investigating judge and Simone Signoret as the financially destitute farming matriarch whose son is the prime suspect, the film similarly frames the French Jura as a place of stagnation and disillusionment, of revelling in past glories, of dying tenant farms and encroaching centralised bureaucracy. It also features the first electronic soundtrackExternal link composed by Jean-Michel Jarre for a film.

A dam of optimism

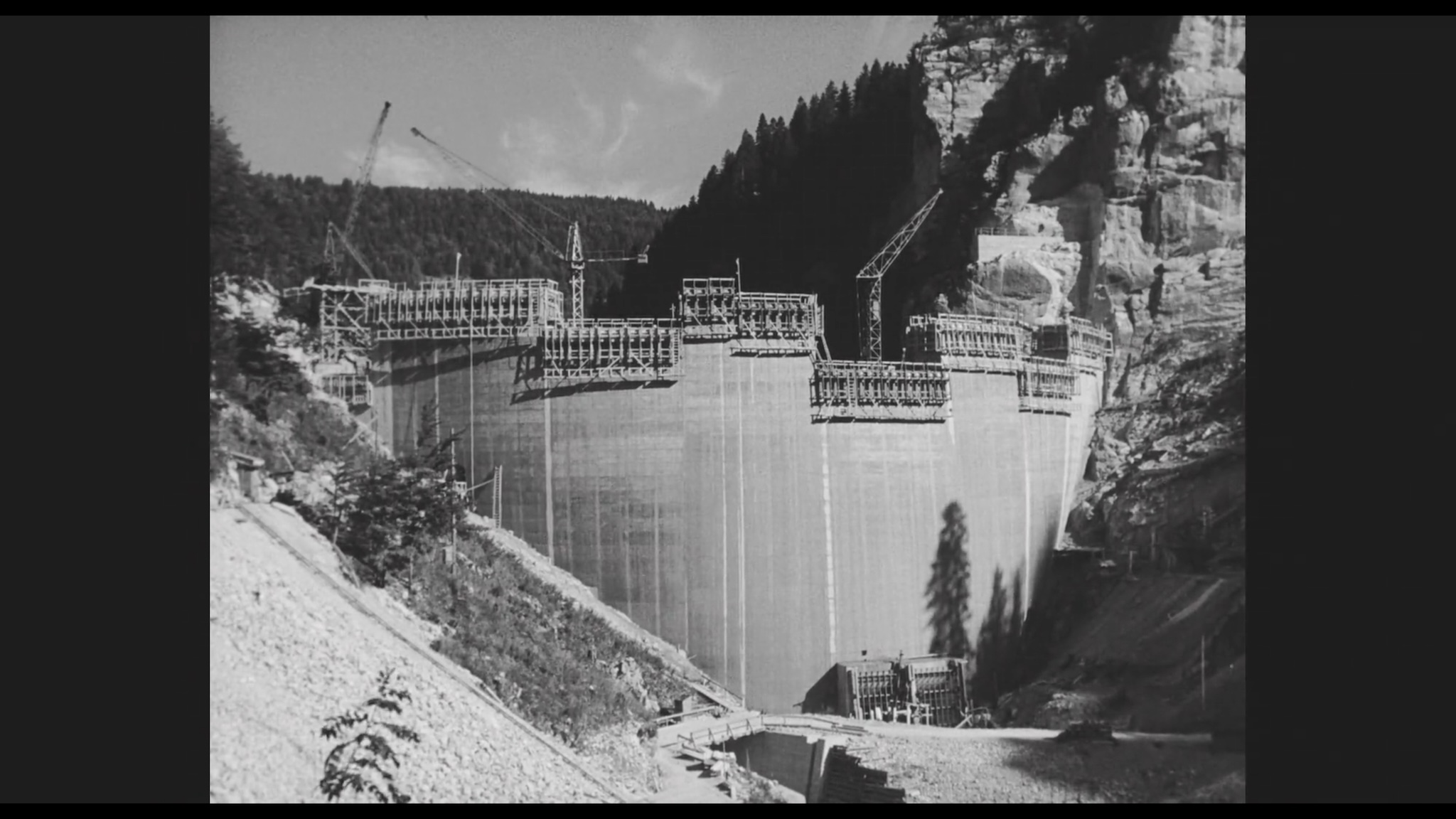

But the Jura wasn’t always a cypher for political radicalism, romanticised Swiss-German fantasy and economic anxiety, as evidenced by one of the retrospective’s prime discoveries: Le Châtelot, Marie-Anne Colson-Malleville’s short 1953 documentary about Switzerland and France collaborating on a dam project in the Doubs river.

It is both a fascinating, gorgeously shot historical artefact from the period of post-war optimism – the jaunty narration eager to stress the good that technology is still capable of – and an eerily prescient film full of quiet unease about the delicate balance between progress and natural beauty that the dam’s builders ostensibly seek to strike.

Indeed, if the Solothurn retrospective had any encompassing diagnoses to deliver on the cinematic Jura, on what the region might evoke (at least on the Swiss side of the border), Le Châtelot’s pervasive feeling of ambivalence might be the most representative summation.

If the Alps signify the past and the plateau signifies the future, the Jura might just be the knotty in-between – the tension between pastoral nostalgia and industrial promise, between patriotic romanticism and the disillusionment with the world one lives in, between political utopia and the messy stew of realpolitik and Molotov cocktails that seeks to achieve it.

Edited by Catherine Hickley and Eduardo Simantob/ts

More

Unrest: Swiss film triumphs at Korean film festival

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.