The Swiss plight of the Yenish makes it to the cinema – at last

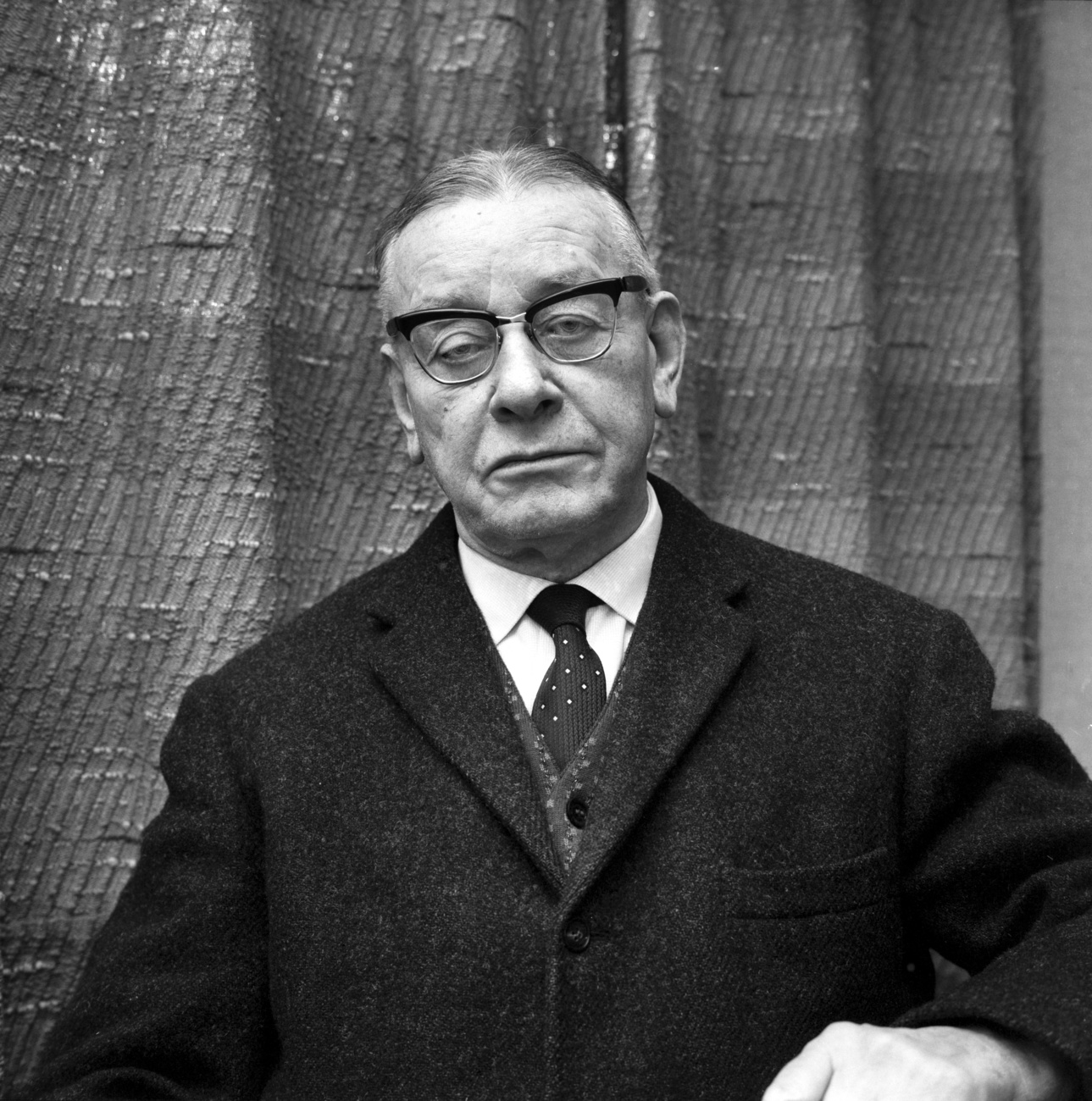

Giorgio Diritti, director of the Italian-Swiss production Lubo, tells SWI swissinfo.ch how he addressed the history and the present situation of the Yenish community in his film, which premiered at Venice Film Festival.

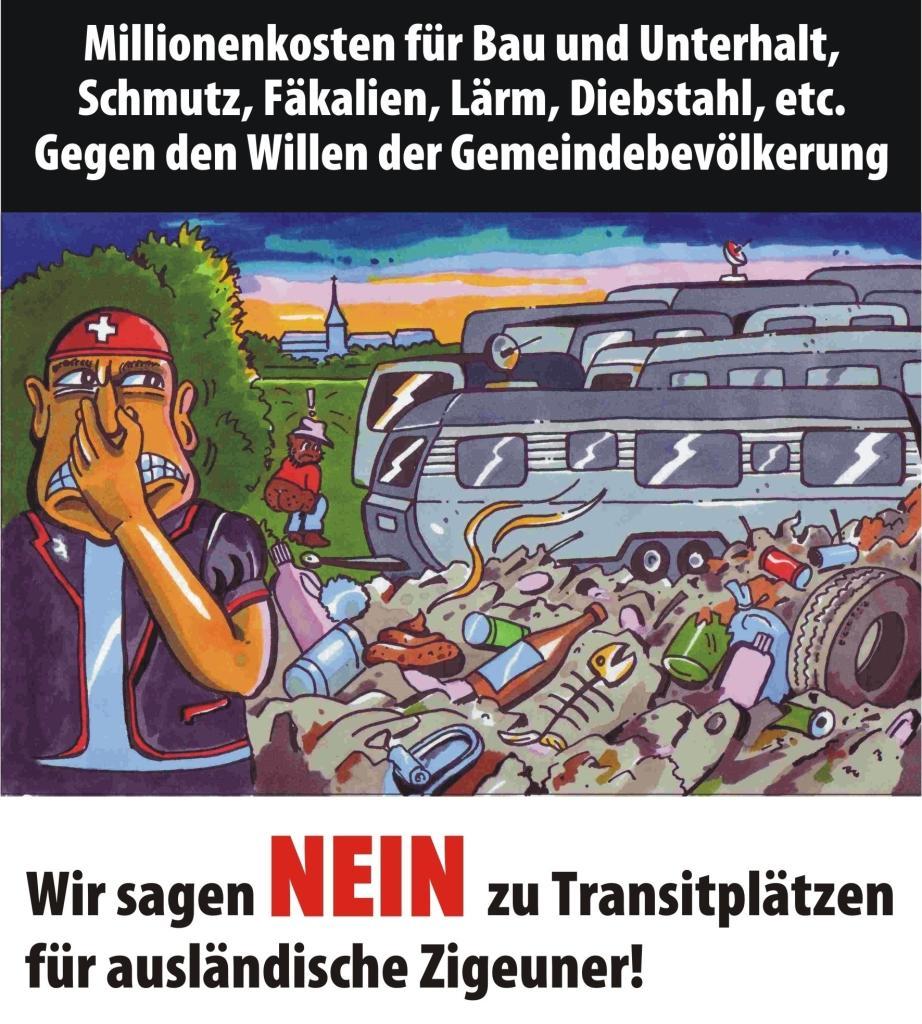

Roma, Sinti and Yenish communities, degradingly put together under the term “gypsies”, never had an easy life in Europe, and Switzerland was no exception in persecuting them. Centuries of segregation and forced assimilation have often been left to the margins of history books leading to generational scars felt until today.

In the specific case of the Yenish, also known as “Travellers”, a few tragic chapters mar their history in Switzerland. The inhumane outcomes of Pro Juventute Foundation’s Kinder der Landstrasse (Children of the Road) programme, for example, carried out from 1926 until 1973, still remain a burning issue within Swiss society. Aiming to “educate and assimilate” the itinerant Yenish people, some 2,000 children were forcibly removed from their families and placed in foster homes or institutions, leaving the victims with long-lasting traumas and psychological problems.

Premiered at the 80th Venice Film Festival, that ended in early September, Diritti’s Lubo addresses this sensitive topic by focusing both on the individual and communitarian dimensions that impacted the Yenish community on many levels.

Following a Yenish man whose wife is murdered and his children taken away from him, Diritti’s film chronicles a story of loss, displacement and unrealised hopes that unfolds over 30 years in Swiss society. After the premiere, we talked to Diritti about the genesis of the film and how he built his story in the light of Yenish people’s suffering.

SWI swissinfo.ch: Lubo is based on Mario Cavatore’s novel Il Seminatore (The Sower) that tells a very important story from a social and historical perspective. How did you come across the book?

Giorgio Diritti: I stumbled upon the novel because a friend of mine introduced me to Mario Cavatore who has also since become a friend. At a certain point, it became important for me to detach myself from the novel and to create some distance. Because in my opinion the key development that needed to be made was to focus on the protagonist, Lubo. That was the path I wanted to pursue. The novel influenced me, as it familiarised me with something I knew nothing about.

SWI: Although the film mostly follows Lubo’s path, we get to discover not only the Yenish community’s plight and traumas but also Switzerland’s distinct position during and after the Second World War. Can you talk about how you framed this historical background in your film?

G.D.: My starting point was the novel. The historical research came later. I went through the official archives which can also be found on the website of Pro Juventute.

But of course, Yenish people also wrote books. For example, Mariella Mehr, who was abducted from her family and grew up with foster families or in juvenile facilities and psychiatric institutions after being considered abnormal. Putting all these different elements together, I built the historical dimension. Then I developed the character of Lubo and his journey, which is rather different from the one he took in the book.

SWI: Lubo has a strong focus on minorities, social outcasts and the way society and authorities of that time tried to erase these differences by trying to create so called respectable, civilised and normal European citizens. Since the actor Franz Rogowski who portrays Lubo does not come from the Yenish community, did you have concerns about representational issues and the way they could impact the statement of the film?

G.D.: I would say yes and no. In my opinion, an actor should have the ability to portray someone belonging to this community. And Franz has proven capable of doing so. Throughout the whole process we worked together and tried to understand where this man really comes from.

Lubo was a man who lived in nature, used his hands a lot. He was an artist and that’s why he had a specific sensitivity. Once he is recruited as a soldier, he ends up in a world which is far away from any interest of his and his imagination.

But Lubo is also a man who can adjust himself. He is a street artist, and we can clearly see this when he gets out of his bear costume. This image already leads us to accept that he might transform himself into somebody else, a person who in “civil society” knows how to behave and speak.

SWI: The film spans three decades of Lubo’s life. We observe both his personal changes and social and political transformations in Italy and Switzerland. These developments are subtly reflected through very impressive and detailed sets and locations. How was the location scouting process?

G.D.: We definitely did a huge work regarding locations and set design. First of all, it was really difficult to find settings or landscapes which would match and mirror how Switzerland was during these periods.

Switzerland is a rich country that has not experienced any recent wars, this means that apart from some historical centres, houses are constantly renovated and refurbished. They look like pieces of jewellery. And I feared that they would look fake. We had to look for locations which would resemble the Switzerland of that time. And we found these locations in Alto Adige or Trentino in Italy.

For instance, the house where Lubo goes to look for help. It was indeed a very long process of research which somehow turned our crew into wanderers travelling in their caravans. In order to find costumes and to have consistency among uniforms, we looked for them in Austria, Switzerland and even in Romania.

SWI: There are 35,000 Yenish living in Switzerland today. Were you in contact with the community while working on the film? Were they somehow involved in the making of the movie?

G.D.: Yes, of course. For example, there’s Uschi Waser, who also attended the premiere of the film. She was one of the abducted children and forced to stay in 13 different institutions. Waser suffered a lot and today she gives lectures in schools to talk about this dark side of Swiss history.

Apart from Waser, I also met her friend Venanz Nobel, who had a very tough experience. He has a beautiful and moving life story, which could have been a separate movie had I known it before. They were the main points of reference for me.

One of my assistant directors went to visit Yenish camps and to recruit them as actors. We found approximately a dozen people who were willing to be involved in the film and came to Italy.

But there was a problem that nobody told us about in advance. Two families had quarrelled in the past, and they informed us that we couldn’t put them together in the same scene because they really hated each other. So we completely changed the schedule and redistributed the roles.

I also remember that there was this one particular scene where an old lady reads tarot cards. That scene was completely improvised because she forgot her lines. But I think this is normal. If you decide to work in this way, you also have a certain kind of poetry that comes with it.

Edited by Virginie Mangin and Eduardo Simantob

More

Switzerland’s nomads face an endangered way of life

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.