The vanishing art of celluloid film projection endures in Locarno

Inside a projection booth at the Locarno Film Festival, a glimpse into the disappearing world of celluloid film.

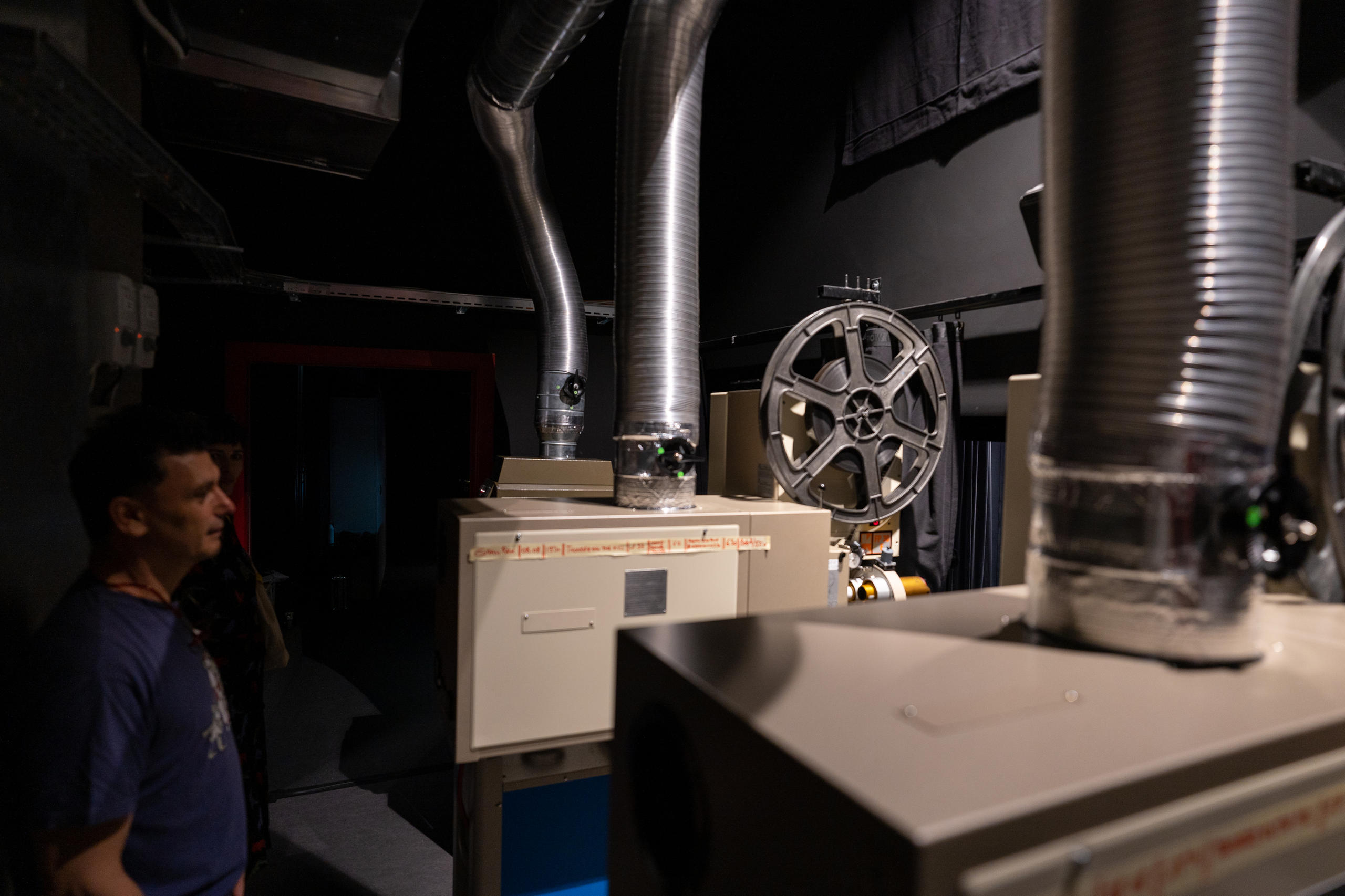

At the GranRex venue in Locarno, projectionist Jean Michel Gabarra has laced up the two Kinoton projectors, a highly sophisticated piece of German technology, with the first two reels of Douglas Sirk’s Thunder on the Hill (USA, 1951). The label from each reel – with information on aspect ratio, sound, etc. – is stuck on the side of each projector’s fan unit as a comforting source of information. Jean walks with determination between the two projectors, occasionally stopping to look through the window at the image on the screen with a contented smile.

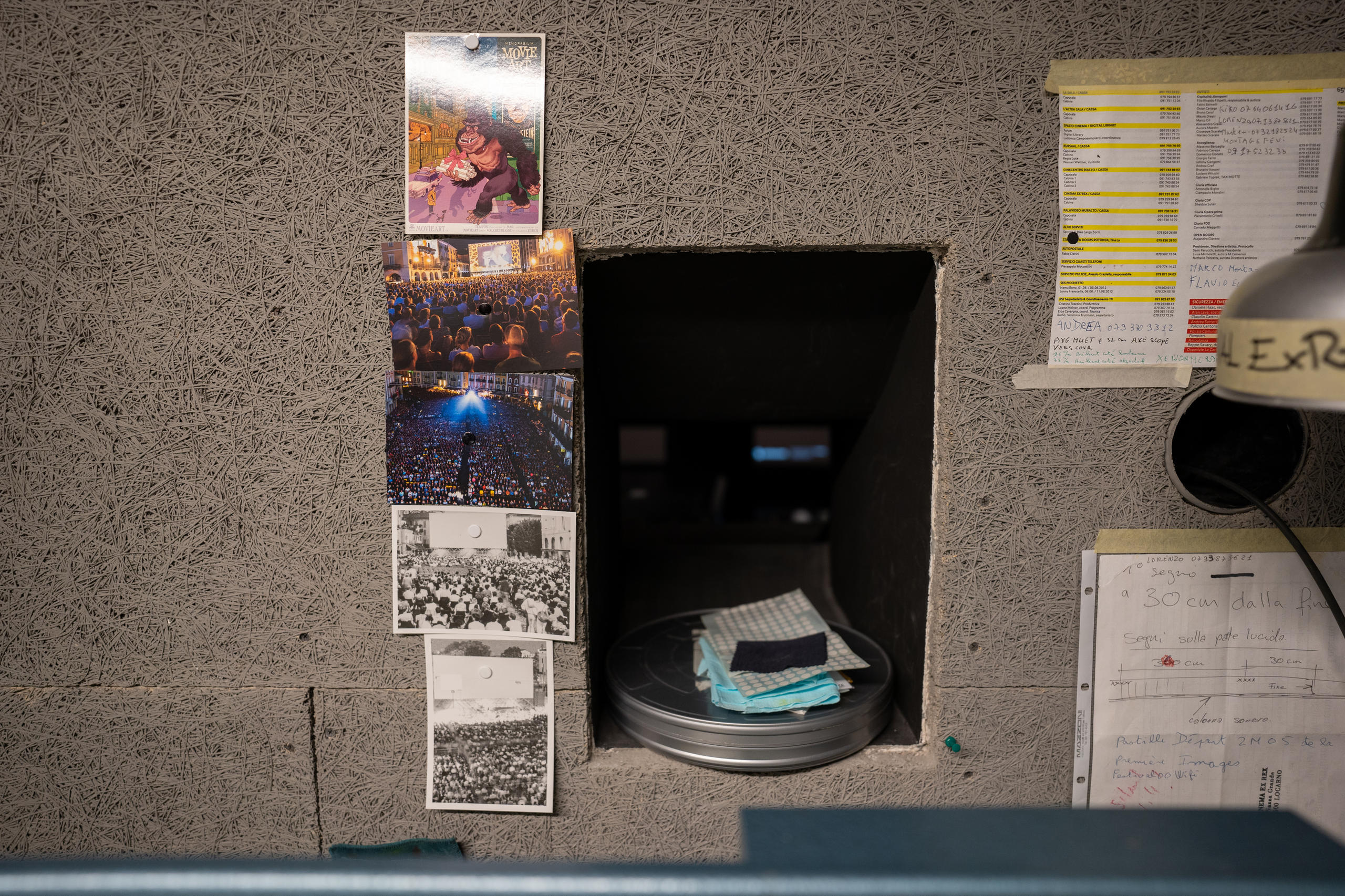

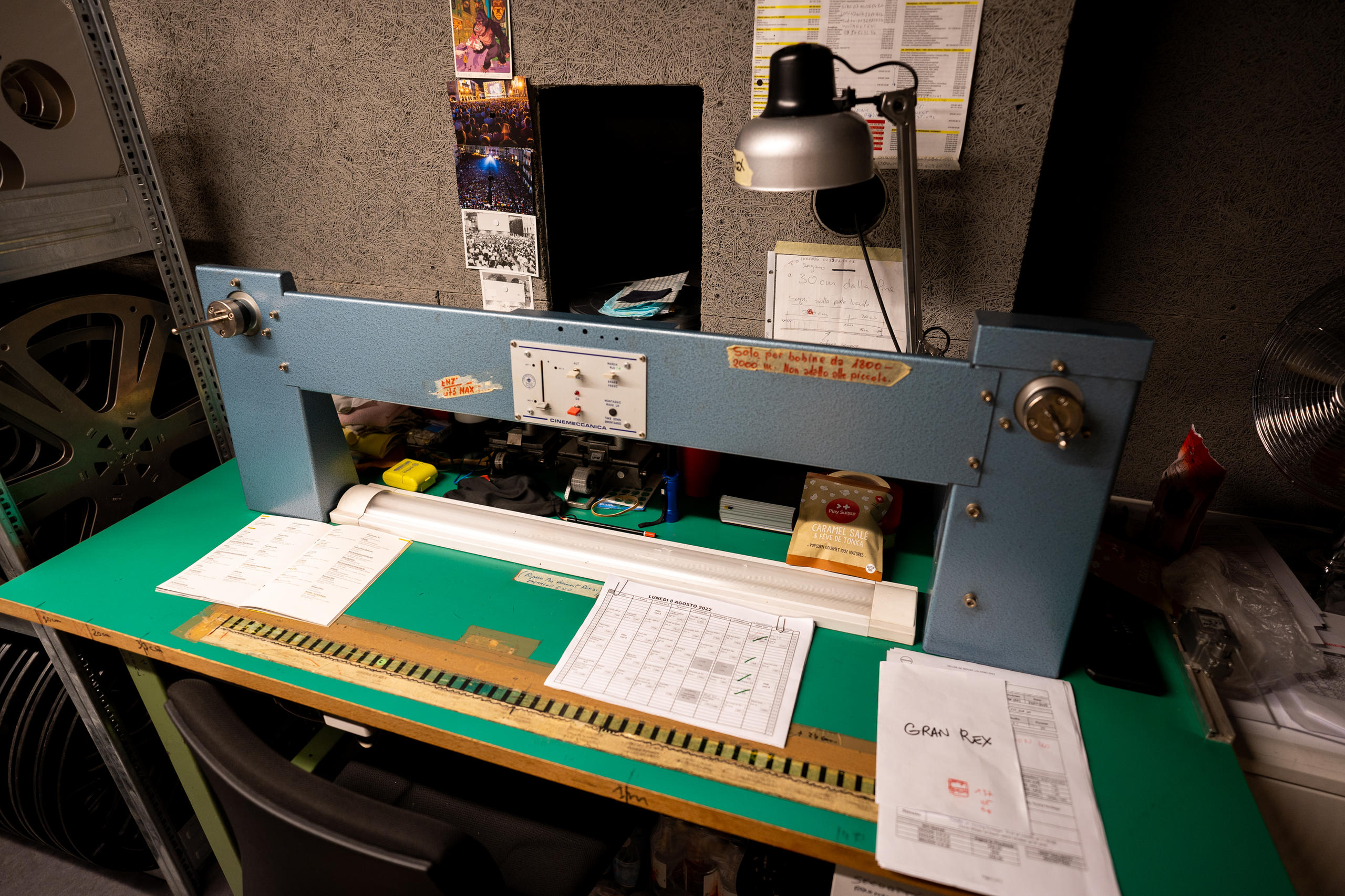

The projection booth is sizeable compared to others I’ve been invited in to, but the two Kinotons – with their giant extraction units – still take up a lot of space. I stay out of the way in the storage room whilst Jean is working. To my right, 35mm prints for the retrospective line a three-tier rack, all labelled and ready to screen to audiences. A blue Cinemeccanica rewind bench – made in nearby Milan and adorned with various notes, instructions, and timetables – will soon shuttle the reels back to their starting points.

In a world of instant gratification, it’s easy to overlook the inconspicuous workers who help facilitate cinematic experiences. This is especially true of film projectionists in an age where celluloid film is still projected thanks to film festivals and special screenings of classic movies.

Alongside other individual screenings, the 75th edition of the Locarno Film Festival featured a comprehensive retrospective devoted to filmmaker Douglas Sirk, largely presented on 35mm prints. By the time a film print hits the screen, it has already been through a variety of processes at the hands of projectionists.

Cristina Caon, the festival’s Head of Print Admission informs me that the prints have travelled here from all over the world. The Harvard Film Archive, the British Film Institute (BFI), the Murnau Stiftung (Germany) and more. It’s a sizeable amount of celluloid, and as we look at this collection it strikes us that the volume of print traffic passing through Locarno would have been much larger before digital projection became the norm.

“There is no longer training for 35mm projectionists in France,” says Jean, who often works for Locarno and Cannes handling projection, “but younger people tend to learn from older people who are still working, or they get lucky because of the film archives.”

This is especially true of my experiences; the knowledge I convey in this article is a product of speaking to projectionists and film practitioners I’ve encountered at various points. In Switzerland, one such enabler is the Cinémathèque Suisse, which is running an adjunctive Sirk retrospective alongside the festival.

Jean learnt from his father before working as an installer of projection equipment. He informs me that several projectionists in Europe largely do other jobs and depend on various film festivals for work. The landscape for celluloid projection decreased dramatically in the later 2000s, as multiplexes began migrating to digital systems.

Cinephiles and casual cinemagoers cite many reasons for enjoying celluloid prints – mostly aesthetic or nostalgic – but it’s just as important that we consider the careers that were impacted by the shift to digital projection at a commercial level. When I began working as an usher at cinema chains in the United Kingdom, I saw career projectionists dramatically laid off or offered reduced hours supporting automated DCP systems (Digital Cinema Packages, the format that feeds cinema theaters today).

After the Thunder on the Hill screening, there was an opportunity to see Gitanjali Rao’s animated short Printed Rainbow (India, 2006) at Locarno’s Piazza Grande, the festival’s iconic outdoor screening space.

In her introductory speech, Rao referred to the organisers’ choice of the 35mm print over the digital file as a rare occurrence. As a result, the print is in great cosmetic condition. The vivid hues bounced off the screen, washing the audience in colour. This was without a doubt my favourite experience at the festival and a memorable introduction to Rao’s filmography.

On the penultimate night of the festival, a 35mm print of Sirk’s Imitation of Life (USA, 1959) made its way to the Piazza. As the audience scamper away from an incoming shower, I watch as raindrops dance in front of the beam of light emerging from the festival’s utilitarian looking Black Box projection booth, fittingly constructed from swimming pool parts.

As each reel comes to an end – denoted by the round hole punch at the top right – I peer back at the booth to see the beam of light change from one projector to the other, a reminder of the work of the projectionist happening inside.

The act of looking back at the projection booth feels uncanny in some regards, because so much about what defines a good projectionist is the ability to work undetected. The silent impact of a seamless changeover between reels cannot be overstated enough.

I think back to attending the Nitrate Picture Show at the George Eastman House several years ago, and how the organisers encouraged the audience to give the projectionist a round of applause before the film. It felt like a radical gesture but one I’d love to see become standard practice, especially as a celluloid print can so often sway audiences into revisiting films or finally experience them for the first time.

From Locarno Critics Academy

Andrew Northrop is a film journalist based in London. He works as a Film & Media Technician at the Slade School of Fine Art. His writings and interviews have appeared in BOMB Magazine, MUBI Notebook, Little White Lies, Millenium Film Journal, Cineaste Magazine, among others.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.