This Brunner, Hollywood’s best Swiss friend, shares star-studded memories

Matthias “This” Brunner shaped Zurich’s cinema culture like few others – and befriended many celebrities along the way. His new autobiography provides a fascinating insight into a life of passion, drama, luxury, film and the arts.

One would be hard-pressed to write a history of international jet set without mentioning Switzerland. It’s the place where film stars and aristocrats spend Christmas, skiing on the slopes of Klosters, St Moritz and Gstaad.

It’s where the likes of Audrey Hepburn, David Niven, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor moved to spend the latter years of their lives. It’s where the mega-rich, following the example of many a classic James Bond villain, used to store their money before the rise of Caribbean tax havens.

Yet for all this glitzy pedigree, the number of Swiss people who can claim to have been a part of the vaunted “Gstaad set” is remarkably small, extending – in the popular consciousness at least – not too far beyond the late movie stars Ursula Andress and Maximilian Schell.

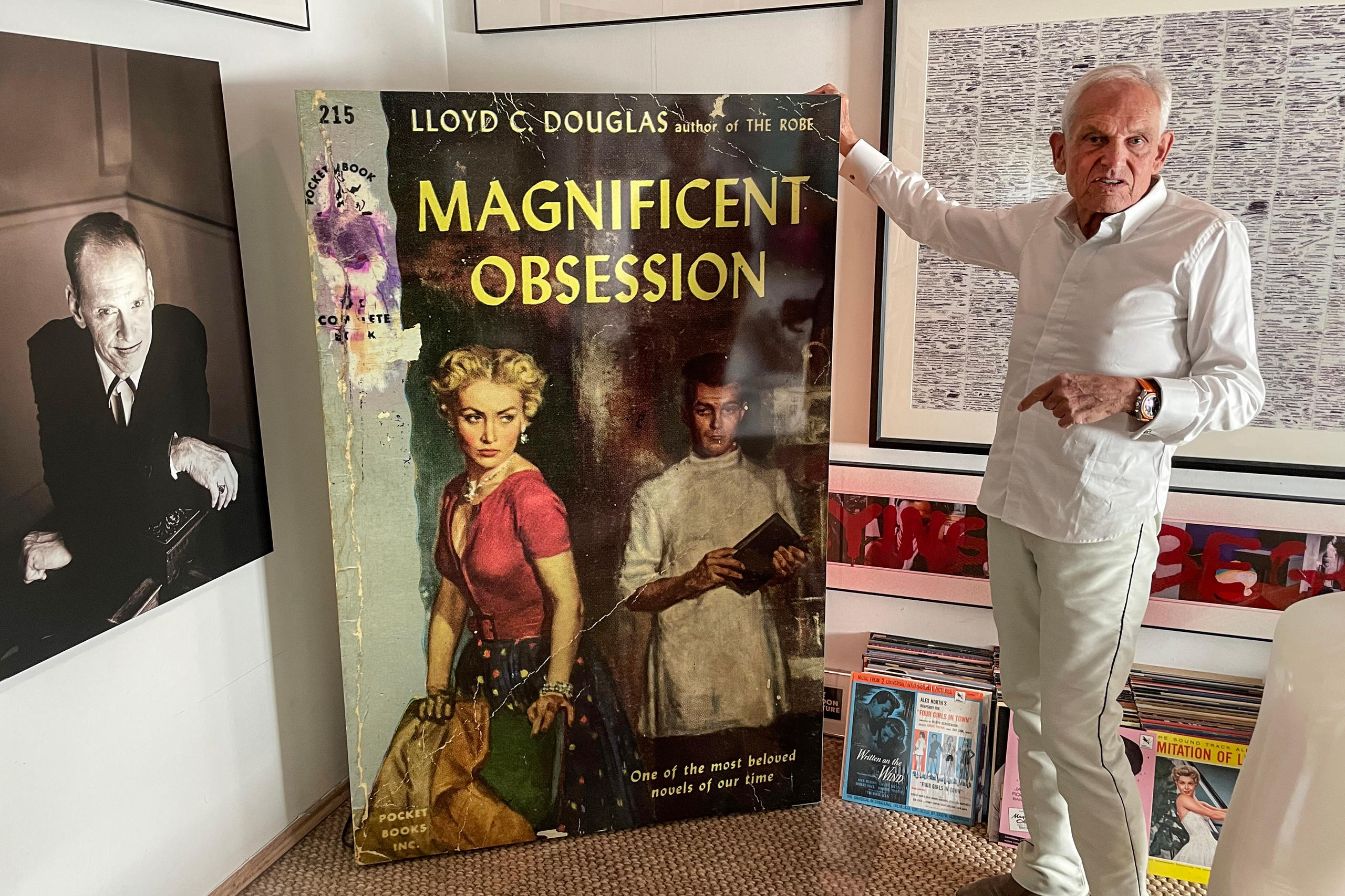

However, that might be about to change, thanks to the book Magnificent Obsessions Saved My Life, whose second edition is set to hit shelves shortly.

Both a deeply personal memoir and a rogues’ gallery of late-century jet set, it sees film curator and artist This Brunner, 78, chronicle his remarkable life – from being taken to court for screening “rude” movies to palling around with Andy Warhol; from getting cold-called by Stanley Kubrick to hosting Robert Mapplethorpe in his own apartment; from spending his winter dining with fashion designer Valentino, Roger Moore, Bianca Jagger and William F. Buckley to losing the love of his life Thomas Ammann to AIDS.

Turning Zurich into a ‘cinéville’

Born into a middle-class Zurich family in 1945, Brunner quickly made a name for himself in the 1960s, organising curated programmes that offered avantgarde films to the city’s blossoming counterculture. “I realised,” he reminisces during a chat at his home that feels like an art gallery, full of mid-century design and contemporary art, “that if nobody was showing [Rainer W.] Fassbinder and [Wim] Wenders here in Zurich, I had to take matters into my own hands”.

What followed was a decades-long success story on the Swiss cinema circuit: in 1973, Brunner opened his first cinema and, in doing so, laid the foundation for the Arthouse cinema chain, which, at the height of its power, operated eight locations throughout Zurich.

Although he stepped down from his executive post at Arthouse in 2009, he retains a keen interest in what goes on in the Zurich cinema scene, which has not been spared from the global effects of changing audience habits and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Following a sad pattern all over the world, in the past five months alone Zurich has seen a major cinema, the arthouse-oriented multiplex Kosmos, declare bankruptcy, and two of the remaining seven Arthouse theatres announcing their imminent closure.

Calling the Kosmos bust “utterly predictable”, Brunner identifies a range of causes – the advent of modern, rivalling arthouse chains eating into each other’s audiences, and the increasing availability of high-tech home theatres.

Perhaps most provocatively, he laments a worldwide move towards what he calls “wishy-washy programming” that fails to create associations between individual cinemas and specific directors, depriving the former of the chance to distinguish themselves through their film selections.

The graceless fall of film criticism

Cultural journalism is not free from blame either, says Brunner. Even though he always struggled with critics panning “his” movies – the memory of newspapers dismissing the early works of Quentin Tarantino is particularly strong – he finds himself especially disillusioned with the current state of criticism: “It’s all about settling petty squabbles with other critics now – about taking extreme positions for the sake of it.”

What he wishes for is more space for cultural debate: “There should be proper arguments, more extensive engagement with difficult, extreme topics. Instead, you turn the page and never hear anything about the film again.”

Yet these criticisms don’t mean that Brunner is turning his back on the cinema culture he helped shape: when we meet him, he is coming off a busy period of catching up on the latest films. The drama The Eight Mountains and the Oscar-nominated Cate Blanchett vehicle Tár both get his hearty endorsement, while seven-time Oscar winner Everything Everywhere All at Once failed to appeal: “Unbearably bad. I never found my way into the story – it seemed to me like the directors were just full of coke. I left the theatre after 90 minutes.”

On the backstage of the jet-set

But how does a film curator from Zurich end up a fixture at hyper-exclusive celebrity get-togethers on private islands and becoming close personal friends with John Waters, Douglas Sirk and Elizabeth Taylor?

In his book, which combines personal anecdotes with blown-up Technicolor film stills and just a few candid photographs of himself and dozens of his famous contemporaries, Brunner credits a mixture of “good cultural fortune and an enterprising spirit”.

Being rooted in the thriving Zurich art scene of the late 1960s put him on the radar of many an international artist, while his efforts to screen the transgressive works of Waters, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Nagisa Ōshima, and Niki de Saint Phalle did as much to endear him to provocateurs of that calibre as it did to put him at odds with Zurich’s vice squad.

And then there was his long-time romantic partner Thomas Ammann, the soft-spoken art dealer from the shores of Lake Constance, with whom Brunner spent, by his own admission, the happiest years of his life – and whose formidable professional status and genial manner earned him a permanent spot on the terraces and yachts of the rich and famous.

Watching the final chapter of capitalism

The section dedicated to Ammann in Magnificent Obsessions is a must-read for those with an interest in post-war stardom: unexpected cameos abound, as do the intimate holiday snaps and stories from the lap of luxury. Famous names are dropped at an astonishing rate, yet the decadence of it all is far from lost on Brunner, who quips that it “felt like experiencing the final chapter of capitalism”.

Ammann’s death from AIDS-related complications in 1993, meanwhile, is described by Brunner in heart-wrenching detail – and prompts him to express his lingering frustration with how the public responded to the crisis in the 1980s: “It made being gay far less acceptable than it had been before,” he recalls.

And although he notes that things have markedly improved for the LGBTQ+ community, he cites far-right violence against gay people and the demonisation of trans people propagated, among others, by the Republican Party in the US as behaviours that must be denounced by the media and the general public in the strongest possible terms.

And what of the future? Brunner admits that the daily news is hardly a source of comfort these days: “I feel sorry for young people,” he says. “How will their lives look in 20 or 30 years? Everything seems to become ever faster, ever crazier, ever more dangerous.”

Yet that’s where good art can truly distinguish itself – by providing visions of what the world could be like. In a sense, it’s what Brunner hopes his own book can achieve: “If my autobiography inspires its younger readers to do the things they love with that much more passion, and to realise that their lives are enriched tremendously by engaging in the dialogue between the arts, then it has done its job. This would make me happy!”

Magnificent Obsessions Saved My Life, by Matthias Brunner. Edition Patrick FreyExternal link, Zurich.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.