Urban versus nature, or how to build cities

New York or Zurich - which city is greener? The answer and the bigger questions the comparison raises were debated at an event on “Urban nature”, held during this week’s Zurich Meets New York festival. Panelist Philip Ursprung elaborates.

Obviously, there is no such thing as “urban nature”. If we follow the artist Robert Smithson, the key figure of Land Art in the 1960s, there is also no such thing as “nature” anyway.

In his view, nature is simply another invention of the 19th century. Nature can be defined as a fiction, produced by industrialisation and modernisation, an image which came into being while the subject it depicts started to vanish.

US-born Philip Ursprung is a professor of history of art and architecture at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, one of the joint organisers of the panel discussion on “Urban nature: Between human and non-human” at the Zurich Meets New York festival.

The proposal of the notion “urban nature” is no claim for a new label. Rather it should trigger discussion and work like a “miniature theory”, as the Dutch theoretician Mieke Bal put it in her book Travelling Concepts in the Humanities, a Rough Guide.

For most inhabitants of Zurich, New York is the very emblem of the urban. New Yorkers, on the other hand, might identify Zurich with the pastoral and thus with “nature.”

In reality, New York is at the forefront of the trend to turn cities green with examples such as the High Line and many urban gardening initiatives, and a tradition of parks going back to Central Park.

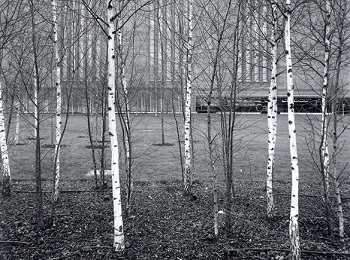

Zurich on the other hand is turning grey, witnessing the most rapid building boom of its history and a trend to cover every remaining spot of the ground with a layer of asphalt in order to facilitate easy cleaning.

New York is regularly hit by natural disasters, storms and floods, while nature in the environments of Zurich is completely domesticated and biodiversity has dramatically shrunken on the “countryside”.

What can we learn from these dynamics? How does the urban and nature, or more generally, the human and the non-human, relate to each other? Which are the implications of this interaction for design, for historical research?

Today, the built environment and the urban are often perceived to be synonymous. Societies the world over – so we are taught in surveys and exhibitions – are constantly attracted to the metropolis. In the near future, we hear, almost all humans on the planet will live in cities.

The grand narrative of the urban has replaced the grand narrative of progress, which dominated the 20th century. At the same time, this new grand narrative becomes questionable as “nature” enters into the focus of our attention by way of global climate change, frequent natural disasters, as well as ever more popular destinations for domesticated natural beauty, retreat and recreation.

swissinfo.ch publishes op-ed articles by contributors writing on a wide range of topics – Swiss issues or those that impact Switzerland. The selection of articles presents a diversity of opinions designed to enrich the debate on the issues discussed.

What is meant by the “urban” and “nature” however, remains largely up for debate. How can we resist this dualistic and teleological way of thinking?

Can the concept of “urban nature” help us focus more clearly on the interrelation between the human and the non-human? Can it help explain pervasive fascinations with the zones of transition (the terrain vague), the wastelands between the urban and the natural?

Can it serve as a platform of exchange between different fields of knowledge such as architecture, urban planning, biology, history and anthropology?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.