Wealth is not all: how gentrification in Zurich has led to housing shortage

Architect Fareyah Kaukab compares gentrification in Zurich with similar cases in other developed countries. As real estate becomes a commodity, she wonders whether this process is leading to cities without inhabitants.

Even one of the richest cities in the world is at pains to deal with its housing crisis, a common problem of practically all metropolises. As the corner shop is replaced by a trendy café and diverse communities by yuppies, Zurich, a city where the middle class represents the lower end of the social pyramid, faces a growing challenge to provide affordable housing.

+ Swiss landlords and tenants are in perpetual conflict

The latest Raiffeisen Bank real estate reportExternal link, published in September, has revealed a 6.4% increase in rental offers for the second quarter of this year, the highest rise in over 30 years. In the gentrified area of Zurich-West, the real estate market continues to surge, with luxury developments becoming more prevalent.

Real estate reports frequently highlight steep rents in Ersatzneubau – older buildings which have been replaced with new ones. For instance, 3.5-room apartmentsExternal link in Zurich-West are listed at up to CHF 8,100 ($9,168), according to the local daily Tages-Anzeiger.External link This contrasts sharply with city-wide averages of CHF1,787 for a four-room apartment and CHF1,470 for a three-room apartment, as reported by the city of Zurich in 2022.External link

The Covid-19 pandemic affected the real estate market: suburban houses became more attractive and office space less essential. Yet, Zurich’s tech and finance sectors expanded significantly during this period, marked by the influx of high-wage employees from startups and the presence of Google’s European headquarters. The latter has been growing steadily since 2004 and now employs over 5,000 people in a city of roughly 450,000.

According to Oak’s Lane Stone CapitalExternal link, a private equity and investment firm, these companies offer salaries well above the local median wage of CHF8,000 per month ($9,000). Bloomberg reports that Google pays software developers, and even beginners, up to CHF200,000 annually. This influx of well-compensated professionals has driven demand for expensive real estate, akin to the situation in San Francisco, where rents have soared by 24% in the last decade.

Gentrification theory and practice

Gentrification, as a general rule, occurs when a neighbourhood becomes more appealing to a wealthier social class, displacing lower-income residents. In Zurich, this process is reflective of the larger housing crisis, where demand for luxury real estate reshapes the city.

More

How Google is driving up rents in Zurich

Gentrification is neither a recent phenomenon nor a new concept. Phillip L. Clay, a professor of housing policy and city planning at MIT, had already done considerable research on the matter when he published his book Neighborhood renewal: middle-class resettlement and incumbent upgrading in American neighborhoods on the transformation of US cities in 1979.

In it, Clay describes the five stages of gentrification, starting with the “Pioneer Phase”, in which artists, bohemians, or risk-tolerant individuals begin moving into battered neighbourhoods, making gradual improvements.

In the second phase, middle-class individuals are drawn to the area, accelerating investment. The third phase sees more substantial private and public investment, often with larger-scale developers entering the scene.

By the final stages, the area is transformed into an upscale neighbourhood, often causing displacement as higher rents and property values drive out the original “pioneers” and lower-income residents.

How Zurich fits into the pattern

Applying Clay’s framework to Zurich-West provides compelling insights. During the 1970s and 1980s, the area experienced political unrest and militant youth movements. These movements were led by the educated youth who moved into Zurich-West, which was initially a low-income industrial zone. This transition epitomised the first stage of gentrification or the Pioneer Phase.

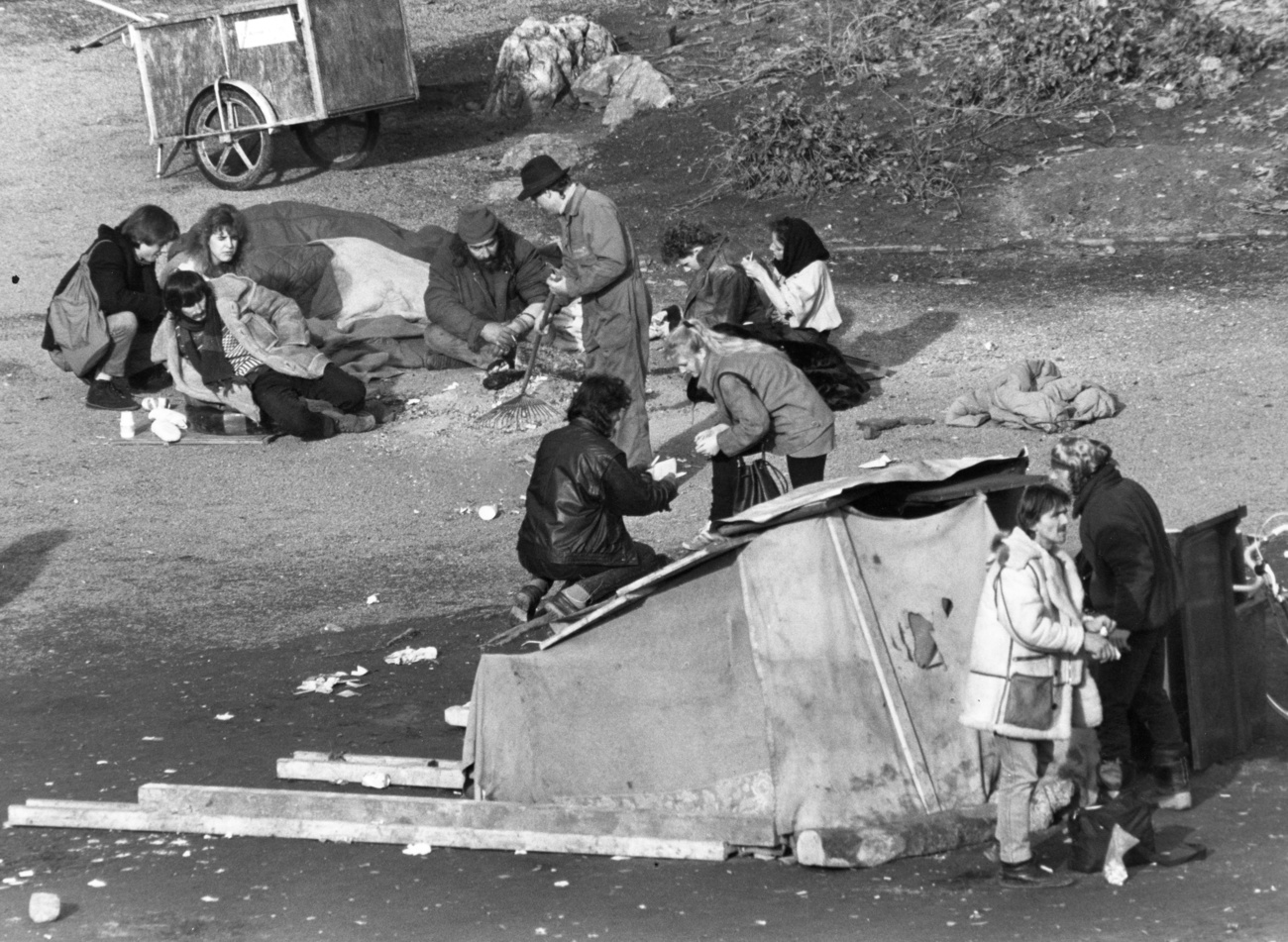

At that time, Zurich experienced a substantial decline as the city centre became home to one of the world’s largest open-air drug playgrounds around the Platzspitz park. That time is still inscribed in the city’s memory in dramatic terms. Zurich’s Needle Park had up to 1,000 users per day. By comparison, Kensington in Philadelphia – a city with a population four times that of Zurich – has around 3,000 daily street drug users.

In 1995, the government led a massive cleanup of the area, repatriating the addicts to their home districts. While the city got international praise for dealing with its drug-crisis through effective harm-reduction policies, it also began to plan long-term urban development projects throughout the area, one that comprises Zurich-West and its surroundings.

In the peculiar case of Zurich, stages one and two of gentrification were not directly connected. The transition to early gentrification was driven by government initiatives to solve a parallel problem rather than by the continuation of the gentrification process started by the pioneers.

In the last 20 years, Zurich-West has experienced profound changes, heading fast to the third stage: an emerging community. Former industrial sites and once stigmatised areas now boast high-rises like Prime Tower, Zurich’s tallest building, surrounded by offices, clubs, restaurants, studios, and new housing developments. This transformation has attracted artists, designers, and architects.

Public investment in urban infrastructure, such as the prolongation of Hardbrücke bridgeExternal link, demonstrates continuity from stage two to stage three – facilitating the expansion of private, large-scale investors. Additionally, the popularity of social high rises like Hardau and Lochergut has skyrocketed. Similar to the Barbican towers in London, these areas are now at the heart of the city rather than on its outskirts, appealing both aesthetically and geographically to the creative middle class. These limited oases of affordable housing, though, are still insufficient. Zurich’s working class in fact live increasingly far from the centre.

Meanwhile, Zurich-West is now clearly entering stage four: mature gentrification. In the 2019 documentary film PUSHExternal link, a bar owner in Brooklyn, New York, observed that creative individuals move in, enhancing the neighbourhood’s appeal, driving up housing prices, and subsequently finding themselves priced out of the area. “You know the first sign that you’re going to have to leave your neighbourhood? It’s when vintage clothing shops show up. Nothing is worse for a neighbourhood than poor people with style.”

More

Homeless to hip: How Swiss housing cooperatives developed

A fifth stage – stabilisation? If only…

In the end, theories like Clay’s oversimplify the complexities of gentrification. In fact, these processes vary, with steps that can be further nuanced or even omitted in economically booming cities. As long as social stratification exists alongside economic growth and government investment, gentrification is virtually inevitable.

In its early stages, gentrification can mean economic growth, increased infrastructure, and improvements in public services and transportation. It can also lead to a more heterogeneous mix of residents, where the less well-off benefit from middle-class pushes for better services. However, beyond mere “stabilisation,” gentrification appears unstoppable, with areas gradually becoming unaffordable.

Ultimately, the debate isn’t about whether cities like Zurich adhere to any given theories on gentrification. What matters is recognising gentrification as a form of social stratification. This ongoing cycle challenges the idea that gentrification can achieve a stable conclusion, suggesting instead a perpetual socio-economic evolution.

So, the crucial question is: in which direction do we aspire to move? Without a conscientious decision from governments and city planners, we risk becoming pawns of bigger players, as we see in cities worldwide where the focus has shifted from striving for better, more livable cities to merely fighting for the recognition of affordable housing as a basic human right.

Without oversight, vibrant communities risk decaying into desolate neighbourhoods akin to London’s Belgravia, where real estate is so attractive that it becomes merely a commodity—a city without people.

Edited by Virginie Mangin and Eduardo Simantob

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.