When Switzerland was the location of choice for Chinese espionage

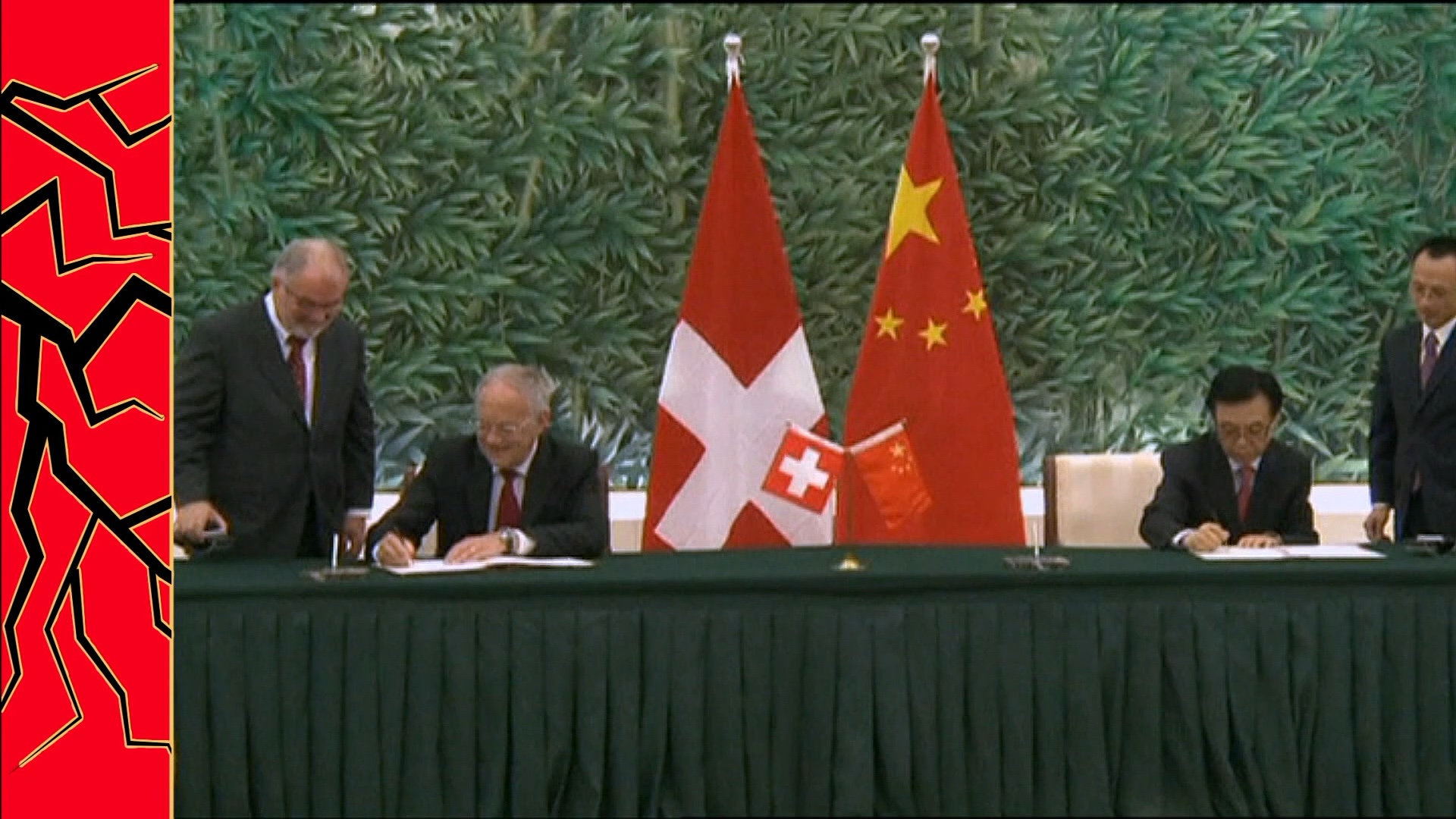

Talk of spying by the Chinese over North America may be dominating the headlines – yet in the 1960s it was Switzerland that stood at the centre of a global Chinese espionage network.

Half a century ago, the world’s newspapers had choice words for the scandal enveloping the Alpine nation. Headlines blared “Bern: the spy centre of Red China in Europe” and “Chinese diplomats train in Switzerland”. Yet the government consistently denied the claims: as late as 1965, the public prosecutor’s office stated that the “fairy tale” about a Chinese spy school in Switzerland had most likely been inspired by the James Bond film Goldfinger.

Files from the Federal Archives, however, paint a different picture. Chinese secret agents set up dozens of international spy networks in the 1950s and 1960s – all of them from their base in Switzerland.

Attractive for spies

How did Switzerland become a control centre for Chinese espionage? Like The Netherlands and countries in Scandinavia, Switzerland was quick to establish diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China. But Bern, located in the heart of Europe, was more attractive than Amsterdam or Oslo could hope to be for planning secret meetings.

As a neutral country seeking to make a name for itself in conflict mediation, Switzerland maintained diplomatic relations with as many countries as possible. Thousands of diplomats travelled annually to attend meetings at the United Nations and other international organisations in Geneva – an ideal setting for spying on delegations and representatives from all over the world.

The fact that the mandate of Swiss counterintelligence was very narrowly defined was also an advantage. The Office of the Attorney General and the Federal Police were only able to take action against persons and organisations that endangered the internal and external security of Switzerland. In short, spying on foreigners in Switzerland was not illegal.

The Chinese embassy and consulate in Geneva employed up to 100 staff in the 1950s and 1960s. In parliament in 1957, government minister Max Petitpierre justified the high number of Chinese officials in Switzerland on the grounds that China maintained from Switzerland economic, cultural and political contacts with numerous western European countries, and also trained diplomats in Switzerland.

Still the Swiss were keeping a close eye on spies from communist countries. A 1963 Political Department report listed 20 Czechoslovaks, six Soviet Russians, six Hungarians, three Poles, two Romanians, two Yugoslavs, and one Bulgarian as suspects. Not a single Chinese national was on the list. In the same year, the department admitted that, despite its suspicions, it refrained from taking action against the Chinese embassy “in the interest of maintaining normal relations with China.”

Snooping against Taiwan

Today it is clear that many Chinese diplomats were also spies. Even China’s first ambassador to Switzerland, Feng Xuan, turned out to be a high-ranking secret agent who helped establish Switzerland as a hub for Chinese espionage in Europe. When he returned to China in 1959, he became deputy director of the Central Investigation Department, now the Ministry of State Security.

In 1966, the Federal Police wrote that Feng had been “one of the most important leaders of Chinese intelligence in Western Europe.”

Taiwanese diplomats also played a central role. For China, Taiwan was – and continues to be – a breakaway province that sooner or later would be reintegrated into the People’s Republic. Many Taiwanese diplomats could be blackmailed into collaboration because they had relatives living in China.

Their involvement went up to the highest ranks. In 1966, Guo Youshou, the cultural attaché at the Taiwanese embassy in Brussels, was arrested. Guo was a regular guest at UNESCO conferences in Geneva in a double capacity: in 1954 he had been recruited in Switzerland by the Chinese ambassador Feng Xuan himself.

More

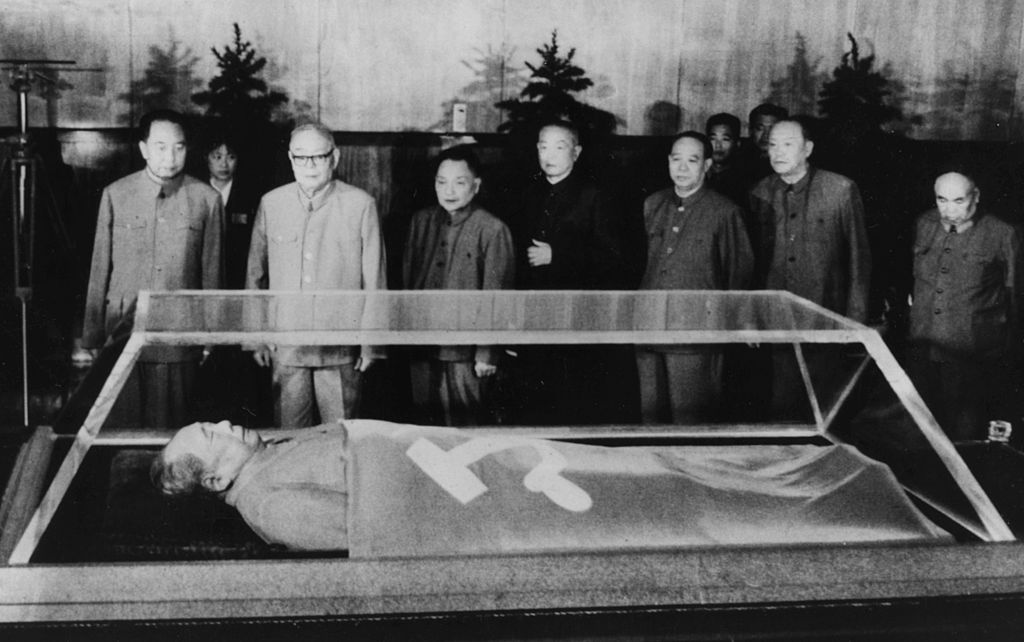

How the death of Mao Zedong ushered in a new geopolitical era

For twelve years, Guo provided China with information on Taiwan and more than 100 Taiwanese diplomats, expats and tourists – all for a payment of around $40,000. His diplomatic immunity protected him from prosecution, but he and his contacts at the Chinese embassy were expelled from the country. This measure was taken discretely to avoid jeopardising good relations with China. No names or reasons for the decision were ever provided to the media.

Because China desperately wanted Western know-how and technologies, Chinese “diplomats” also hired numerous Chinese-born scientists and students throughout Europe. Like diplomacy, journalism provided a welcome cover: some intelligence officers worked for the state news agency Xinhua, which was described by the Federal Police as “the driving force of Chinese intelligence in Western Europe”.

“Its central location allows it to coordinate reports coming in from the entire Western world in Paris and then relay them to Beijing via Bern and Geneva,” it said.

Investigative difficulties

In 1967, of the nearly 100 Chinese officials based in Switzerland, 30 were suspected of being agents. Another 30 were assumed to have intelligence duties. Swiss counterintelligence, however, did not sit idly by and watch the Chinese in Bern and Geneva: phones were tapped, diplomats were followed, and visitors were identified and investigated whenever possible.

Swiss officials even cooperated with the CIA and Interpol – but with little success. The large number of Chinese diplomats seemed unmanageable. As early as 1955, the Swiss attorney-general’s office reported that “it is almost impossible to distinguish the Chinese from each other, as they all look very similar.” Indeed, numerous attempts to trace the activities of suspected Chinese spies came to nought because the Swiss witnesses were simply unable to clearly identify the individuals.

For the same reasons, the communist activities of the Chinese were considered to be of little danger: Chinese subversion in Switzerland, according to the secretary- general of the Political Department in 1964, was not a big problem: “Because of their skin color alone,” he said, “the Chinese can be kept under control at any time.”

Since the Federal Police were not given enough manpower, local police officers were assigned to tail suspected Chinese spies and collaborators. Again and again, these tails broke off – because of a lack of personnel, bad weather, confusion caused by one-way streets, or because the suspect had boarded a train. The police officers contacted at the supposed destination often waited in vain on the station platform – the suspects had simply vanished into thin air.

However, even if it could be proven that a diplomat had engaged in espionage, he or she rarely had to fear consequences. Any measures taken against a suspect would have raised the prospect of retaliatory action by China against Swiss diplomats or Swiss businesses.

Adapted from German by Sue Brönnimann/gw

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.