Young filmmakers target Africa and hit Switzerland’s post-colonial legacy

This year, the Visions du Réel Film Festival's national competition featured three Swiss documentaries set in Africa. Using different styles and narratives, they reflect the theme of post-colonialism and its contemporary significance within the Swiss film industry.

Switzerland’s Visions du Réel, one of the world’s leading documentary film festivals, featured 154 films from 57 different countries – the highest number in its history. It’s no wonder, perhaps, that the festival’s national selection of Swiss documentaries is often overlooked by its foreign guests, who either focus on the two main competitions or try to catch up with the latest hits from other festivals.

But the national selection offers insightful perspectives on contemporary Swiss documentary production. In this year’s programme, no less than three Swiss-made documentaries in the competition brought stories from Africa.

Football and friendship

Sarah Imsand’s Kevine et Fortune is a heartfelt exploration of the friendship between two young women from Cameroon who share the dream of becoming professional football players abroad. Fabienne Steiner’s Fitting In is a study of an all-male student residence at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, where the long-term impact of the apartheid regime persists. And Laurence Favre’s Lettres au Docteur L is an experimental exploration of diaries written by a 19th-century doctor and missionary sent to southern Africa.

Each of these films, through different narrative and formal strategies, tackles the ongoing reverberations of centuries-long Western colonial practices within specific communities. They are modest yet perceptive attempts to challenge entrenched systems of economic and cultural hegemony.

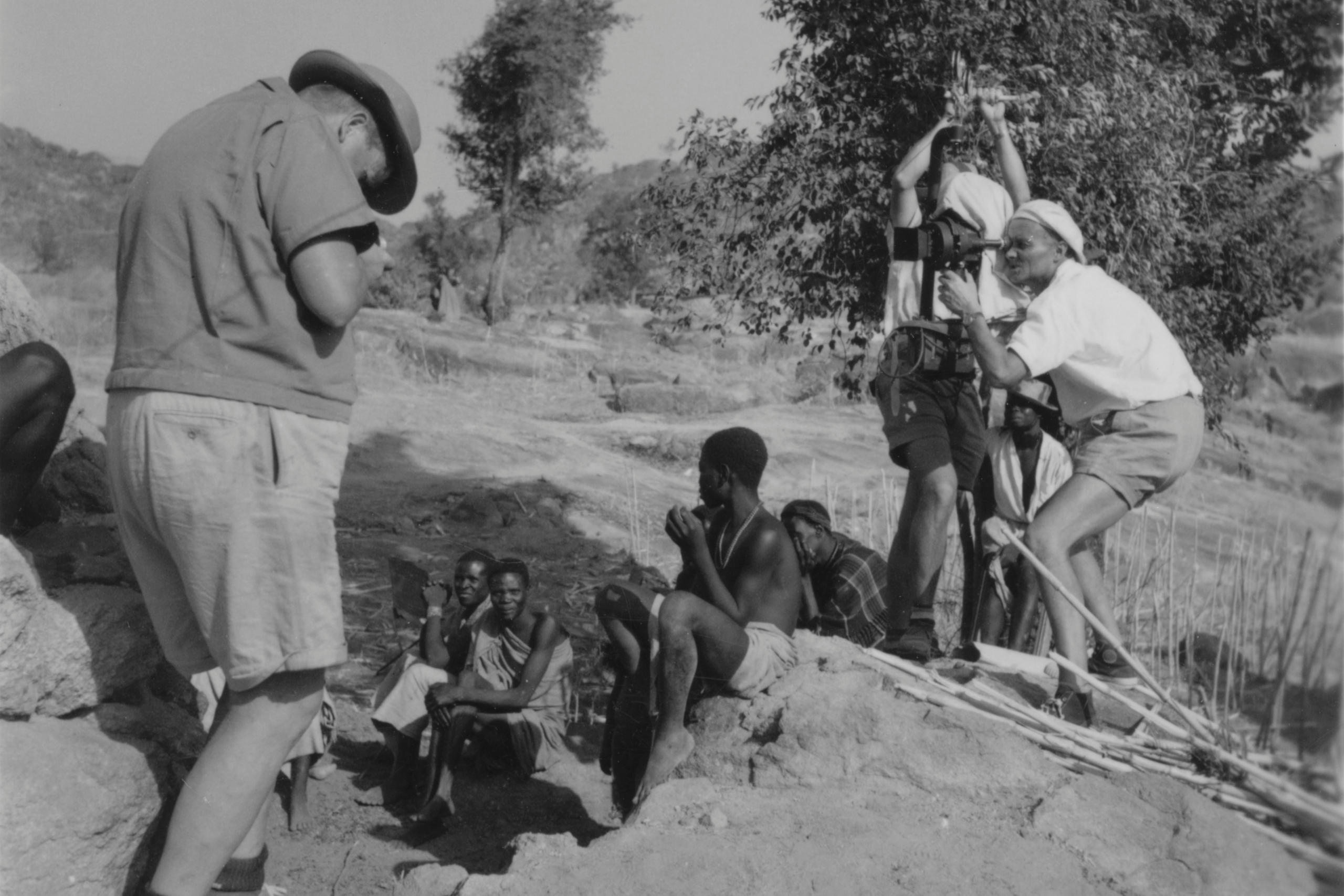

As a creative form, documentary filmmaking has always inherently involved an asymmetry of power between the subject in front of the camera and the person behind it — the latter traditionally and historically being a Western white male — and Swiss documentary makers were no exception. In this regard, African Mirror, Mischa Hedinger’s 2019 archive-based documentary about the Swiss traveler and filmmaker René Gardi, offers a compelling analysis of this stereotypical figure.

However, the tide seems to be turning. Considering the growing cultural and ethnic diversity of SwitzerlandExternal link, the three films in Visions du Réel’s National Competition – all first features made by women, reflect a new paradigm, one that is transnational, decentralised, and gender-diverse.

More

How René Gardi shaped Swiss views of Africa

Mixed heritage

Imsand seems well aware of the limits of filmmaking: “Kevine et Fortune is a first and important step for me, and I want to keep pushing further – by constantly challenging myself to improve existing forms of representation,” she says. Born to an Ethiopian father and a Swiss mother, Imsand says she is acutely aware of the discriminatory tendencies against people of African descent in Swiss society – a sharp understanding of the different levels of privilege that she has transposed into her work.

The origins of Kevine et Fortune can be traced back to a joint academic research project between Switzerland, Cameroon, and Senegal on young women’s engagement with football in Africa. Imsand accompanied the findings with an audiovisual production.

Her documentary unfolds with surprising tenderness and warmth, making friendship, rather than any overarching sociocultural analysis, the centerpiece. “I didn’t want to give the impression that I was making generalisations about Cameroonian society and the conditions of women,” Imsand says, “because that would have put me in a dominant position.”

Imsand’s next project will be a personal documentary about her father’s family, through which she hopes to examine her Ethiopian heritage. “Having grown up in Switzerland, I want to explore my position in relation to my Ethiopian family – the things I did and did not inherit from them, but also the reasons why they chose not to transmit certain things, and what those things are,” she says.

Errors of the past

Favre, the director of Lettres au Docteur L, grew interested in missionary archives after she inherited films and letters belonging to a family member who had worked as a Swiss missionary – a legacy she first explored in her short film Nwa-Mankamana (2013).

“It’s fundamental to always ask yourself how not to repeat the same errors as those from the past,” she says. In Lettres au Docteur L, she adopts a dialogue across different temporalities and places, inviting people from southern Africa to address Docteur L through letters. Read in voice-over, these letters become sound capsules that travel through time.

Referring to the recent rise in exhibitions addressing colonialism in Switzerland, Favre stresses the importance of caution in using terms like “decolonial turn”: “There’s a tendency to look at the archives and say, ‘Oh, how terrible the past was,’ as if structural racism didn’t persist over time,” she notes. “We’re at the very beginning of some rather timid attempts, which we often pretend are much more substantial than they actually are.”

Switzerland’s “colonial gaze”

In former empires like France or Belgium, where colonial legacies persist and take on new forms, cinema frequently serves as a tool of redemption or retribution. In this regard, Switzerland – a country which never officially held colonies, yet fully assumed the white European colonial gaze – occupies a peculiar position.

“Switzerland has long had a tradition of filming abroad,” notes Vision du Réel’s artistic director Émilie Bujès, when asked about the presence of three Africa-centered films in the selection. Although she has not observed a substantial increase in their number recently, Bujès points out that there have long been films made in – or about – marginalised economies.

Bujès sees this as less a matter of culture than of budget and economic reality: “Swiss filmmakers could go and shoot in four different countries because they have the budget to do so. It’s a fact we can’t ignore.”

While European audiences may still be relatively unaccustomed to post-colonial readings and historical revisionism – and may even perceive a potential threat in what is now often referred to as the “woke movement” – these discussions nonetheless reflect a broader global shift within the film industry.

In response to these changes, Bujès expresses trust in audiences: “The legitimacy of one’s perspective is a difficult matter to discuss, but I’d refrain from making definitive and immutable judgments, because I believe we’re intelligent enough to assess the relevance and value of a film with the tools we have at our disposal.”

Edited by Catherine Hickley/gw

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.