‘Tower of Hope’ reaches out to Yerevan and Nuuk

In the middle of the vast Canadian prairie there is a modern lookout built on sacred aboriginal lands, the Forks. From here, the recent democratic events in Armenia and Greenland don’t fail to impress and encourage even if they take place far away.

It was one of these historic goosebumps moments. On Monday this week, Armenia’s long-term autocrat Serzh Sargsyan, a former general, published a brief but extraordinary statement, which read:

“This is the last time I will speak to you as the head of the government. Nikol Pashinyan was right. I was wrong.”

Pashinyan is the leader of the democratic opposition, who was arrested several times in the last decade and imprisoned after criticizing Sargsyan, most recently on April 22.

Following the model of Russian President Vladimir Putin, the corrupt autocrat let the parliament in Yerevan elect him as the new prime minister a couple of weeks ago. By Monday morning hundreds of thousands of Armenian citizens had gathered in most cities of the landlocked Caucasian nation.

It was the 11th consecutive day of national protests as Sargsyan, using a contemptuous trick, had tried to stay in power after leaving the presidential palace a few weeks ago.

Over the last two years, he orchestrated rigged elections and referendums to move the country farther away from democracy, like in neighbouring Turkey, Iran and Azerbaijan. And then this sudden admission of guilt by a political leader, which – as the British Guardian newspaperExternal link put it – “seemed out of place in modern politics”.

Heart of the prairies

In fact, modern politics are full of brave people struggling for freedom and democracy. If you don’t believe me, come and join me in Winnipeg, where I have been staying this week, to check out a new intriguing global democracy centre, the Canadian Museum for Human RightsExternal link.

Inaugurated in 2014, the museum is situated on the Forks, an island south of downtown Winnipeg half way between Canada’s Pacific and Atlantic coasts. Here the various native people of central Canada have met for many centuries to dialogue and make decisions.

“Democracy as an idea, procedure and practice is much more robust and resilient than many may believe nowadays,” said John Young, long-time lecturer for human rights and museum director, during a conversation.

Housed in a fascinating piece of architecture, his institution, which is financed by the Canadian government, features both moments of darkness and light about human rights and democracy, and it gives reasons for hope and optimism. (I will come back to the new museum and its leadership in future reports).

The visual highlight the Human rights museum is a 100 metre-high – seemingly unfinished – construction, called the Tower of Hope.

Standing up there, with three rivers merging at the Forks on one side, the skyline of downtown Winnipeg on the other, and beyond the immense flatlands of Manitoba, it made me think:

The developments and achievements of the brave Armenians, who despite their harsh international environment and frustrating internal setbacks have never given up, felt as important as they really are.

A milestone not just for Armenia, but also for the wider Caucasian region and the world.

Once upon the time, the Armenian territory was a major player bordering Persia (today Iran), the Ottoman Empire (today Turkey) and Russia. The territory has shrunk to less than 30,000km2, and most Armenians (more than seven million) now live outside their homelands. Only about three million live in Armenia.

The big Armenian diaspora residing in Russia (2.25 million), the United States (1.5 million), and France (about half a million) help shape the republic. Putin’s army protects Armenia and ensures its security, while American or French concepts of modern democracy inspire Armenians, especially at the local level.

Greenland’s way to independence

But democracy is not won yet even if the Armenians got rid of an autocratic leader this week.

Looking northwards from Winnipeg’s Tower of Hope, my thoughts went to a second place on earth, which this week saw another step forward on its long way to democratic independence: Kalaallit Nunaat, better known as Greenland.

On Tuesday, citizens this Tuesday went to the polls to electExternal link a new national parliament, the Inatsisartut.

With less than 60,000 people on an area as big as western Europe (2.1 million square kilometres), Greenland has been exceptionally successful in overcoming centuries of colonialism and racial policies directed against the native Inuit.

In a series of popular votes (binding referendums) the Greenlanders decided to become an autonomous state within the Danish Commonwealth (Rigsfelleskap) in 1979, and then to leave the European Union in 1982.

More than 20 years later, Greenland in 2008 adopted the principle of democratic self-determination (with a majority of 75%), giving the world’s biggest island the right to decide when and how it wants to secede fully from Denmark.

Many other nations around the world – including Catalans, Scots, Kurds or Californians – would certainly like to see such possibilities for themselves.

But such an independence process in dialogue with former colonial and current central powers needs the firm commitment and transpartisan consensus like in Greenland, and in addition – a lot of patience.

This is one of the key lessons of my ongoing 200-day #ddworldtour: it makes sense to learn from cases and examples outside the main media spotlight.

Beside the many practical differences, there are often very similar forms of conflicts and patterns. The wish for freedom, self-determination and democracy in Armenia and Greenland is similar to the many stories shared at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, as told by women and men from across the globe and all walks of life.

These values are universal indeed – and will prevail if we continue to report and support them.

Swiss-Swedish author and journalist Bruno Kaufmann is on a world tour to explore the state of democracy visiting more than 20 countries on four continents until May 2018.

swissinfo.ch has been publishing a weekly Notebook and multimedia reports by Kaufmann as part of its coverage of direct democracy issues.

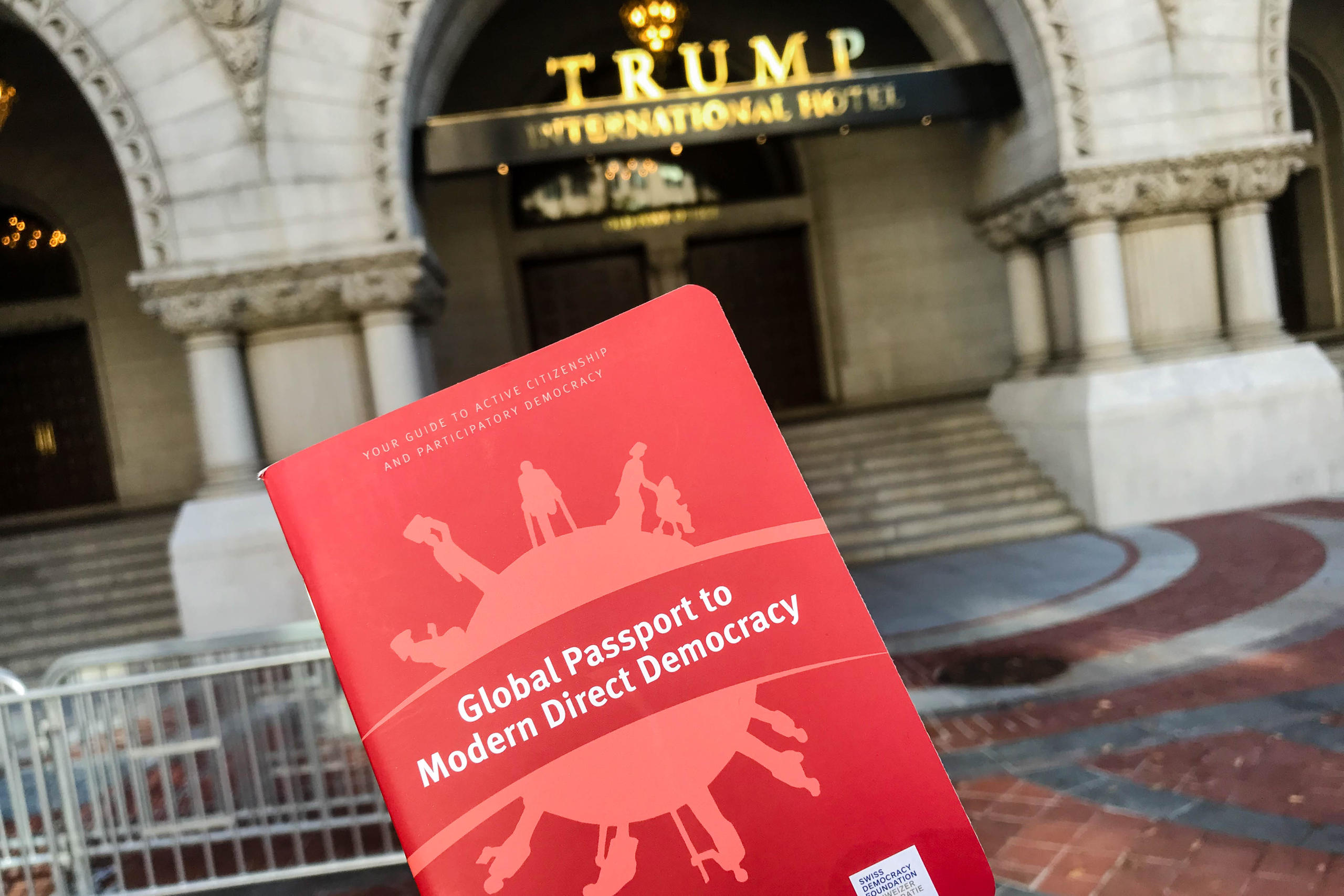

Kaufmann’s democracy world tour is mainly sponsored by the Swiss Democracy FoundationExternal link, where he is the director of international cooperation. The Swiss Democracy Foundation hosts various projects and platforms linked to participatory and direct democracy across the globe, including Democracy International,External link the Direct Democracy NavigatorExternal link and the Initiative and Referendum Institute Europe.External link

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.