Brexit, or the explosive force of separation

Britain’s referendum on Thursday on whether to leave or stay in the European Union is a first. For the first time since the 2009 EU Constitution came into force, a member state may make use of its exit clause. Under article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, “any member state may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements”.

The Brits would not, however, be the first people to turn their back on Brussels. On February 23, 1982, 53% of voters from Greenland decided to withdraw from the European Community. The former Danish colony with just 50,000 inhabitants took the decision while weighing up new autonomous rights it had obtained a few years earlier.

Indeed, since the early 1970s there have been several Europe-related votes within Europe. On March 23, 1972, France held a referendum on whether to enlarge the European Economic Community to include Denmark, Ireland, Norway and Britain (68.3% of voters agreed). Since then, voters have been able to have their say on more than 60 occasions on joining the EU or deepening integration.

These included votes by non-EU countries such as Switzerland. Since 1972, when 72.5% of Swiss voters agreed to join the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), the Swiss have gone to the ballot box ten times to express their views on European issues.

More

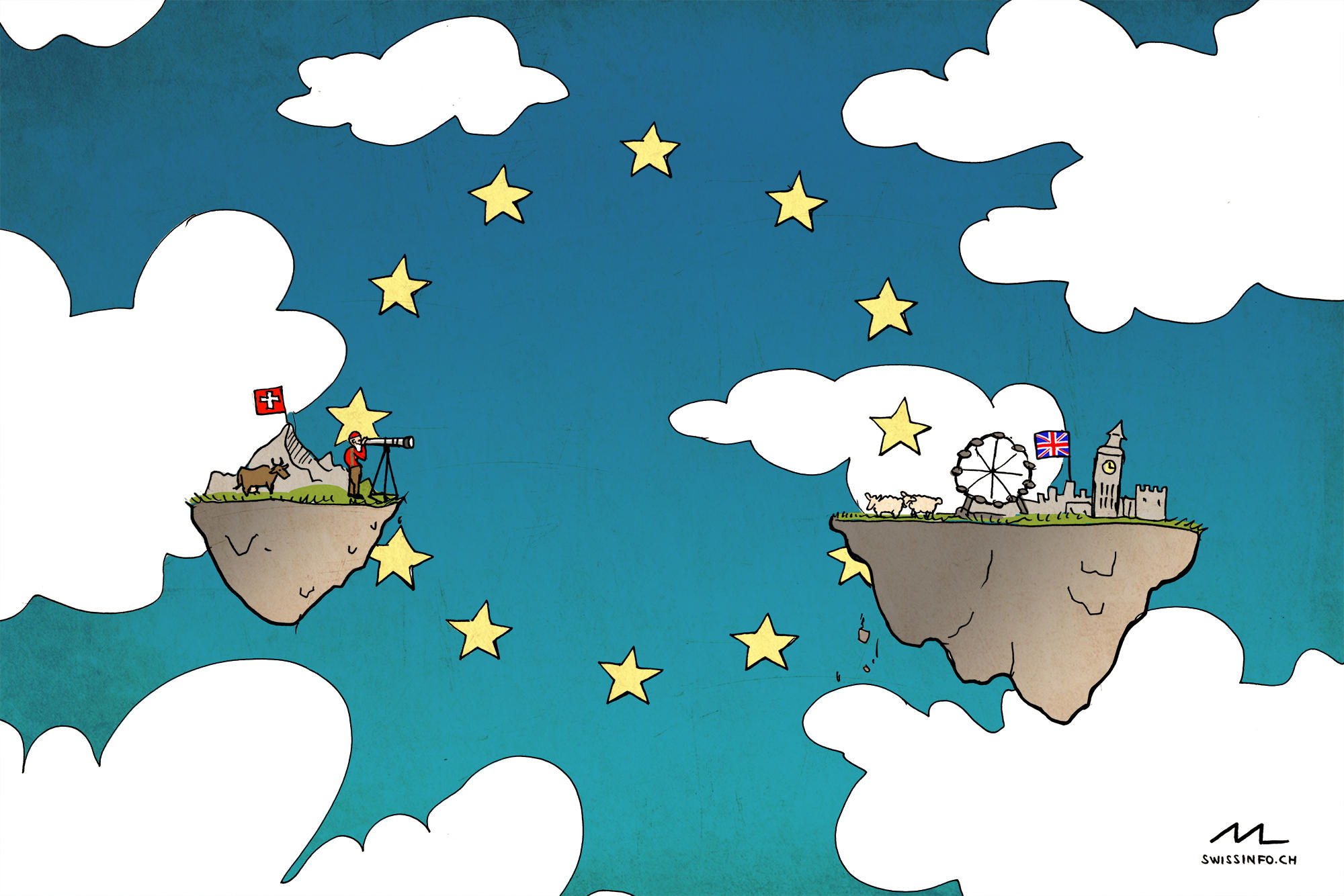

Brexit and the Swiss connection – a guide

In Switzerland and 25 other European countries, this has led to positive EU votes in over two-thirds of cases. But the negative decisions tend to stick in people’s memories. For example, in 1992, a referendum on the Maastricht Treaty was rejected by 51% of Danish voters and the same year 50.3% of Swiss voters turned down joining the European Economic Area (EEA).

Referendums become particularly sensitive when they ask citizens whether they want to leave a particular political community and join another one. There are numerous examples from recent history.

On March 16, 2014, 96% of residents in Crimea voted to secede from Ukraine and join Russia. Twenty days earlier, pro-Russian military units had occupied the government and parliament buildings in the Crimean region and deposed the elected representatives. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) was denied the possibility of observing the vote.

Abusing referendums

While the United Nations General Assembly declared the Crimea referendum “invalid” and the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe described the decision as an “abuse of the referendum instrument”, Russia used the people’s vote as an opportunity to annex the Crimean peninsula within two days.

In Switzerland, the long-running case involving canton Jura and calls for territorial autonomy shows how things can go quite differently.

This French-speaking and majority Catholic region in northwest Switzerland had been annexed to the German-speaking and majority Protestant canton of Bern at the Vienna Congress in 1815.

While the following 200 years saw isolated acts of violence by separatist groups (for example the Jura Liberation Front at the beginning of the 1960s), solutions were sought first and foremost via the constitution and direct democracy: in the past half century, a total of more than 50 ballots at all levels have continued to find new solutions.

The obvious highlight was the nationwide votes on September 24, 1978, in which voters recognised Jura as Switzerland’s 26th canton.

But almost 40 years after that historic vote, the process is not yet complete: in 2017, several communes in the Bernese Jura region will be able to vote on whether they want to remain in canton Bern or switch to canton Jura.

More

Difficult birth of a canton

Free, fair and secret?

Whether it’s Crimea, Jura, Brexit, South Sudan, Scotland or Catalonia, the world can learn a lot from secession movements that are more or less democratic.

First, a lot depends on whether a vote takes place within a stable legal context. Whereas the referendum on Scottish independence on September 18, 2014, had the blessing of the British parliament, the public poll in Catalonia the same year about breaking away from Spain took place against the wishes of the government in Madrid.

Second, the time allotted for a public debate in the run-up to the referendum plays an important role, as highlighted by the cases in Crimea and Jura.

Finally, the (direct) democratic sustainability of a secession referendum also depends on the level of administrative care. This ensures that, among other things, the secrecy of the ballot and the freedom and fairness of the plebiscite are guaranteed.

More

Switzerland’s special EU deal

Bruno Kaufmann is president of the Initiative and Referendum Institute Europe and co-chair of the Global Forum on Modern Direct Democracy. He is Editor-in-Chief of people2power.info, a direct democracy platform created and hosted by swissinfo.ch.

This text is part of #DearDemocracy, swissinfo.ch’s platform on direct democracy.

In a nutshell: Brexit, Crimea, and the Jura region in Switzerland – there are different ways of trying to resolve conflicts over autonomy and secession. What are the lessons to be learnt for democracies around the world?

Translated from German by Thomas Stephens

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.