Populism – what’s in a word?

As political change and fuzzy rhetoric spreads across Europe and beyond, there has been much talk about populism and its discontents. What does the word actually mean?

Cas Mudde, the Dutch academic widely regarded as an authority in the field, says that populism is an ideology that separates society into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups—“the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”.

Margaret Canovan, the late British academic best known for her analysis of the works of Hannah Arendt, wrote a book called “Populism” in 1981, where she identified seven types; she also said the term itself couldn’t be succinctly defined.

Princeton University’s Hans-Werner Müller also highlights the “elite vs people” dichotomy and says that populist rhetoric is notable for its repudiation of political pluralism – anyone that’s not “the people” doesn’t count, he says.

For dictionary.com, populism is “a political strategy based on a calculated appeal to the interests or prejudices of ordinary people” (ordinary: “of no special quality or interest; commonplace; unexceptional”).

For urbandictionary.com, populist is “an adjective used by snobby intellectuals and elitists basically as code for ‘this is what morons like’.” (moron: “to be stupid. Not very clever, most likely to be lacking in intelligence”).

The New York Times, a snobby intellectual publication, has used the term to describe Viktor Orbán, Donald Trump and Steve Bannon, among others.

Steve Bannon agrees; he has gladly proclaimed himself a herald of the “populist revolt”. Donald Trump has spoken much of “the people”, but less of “populism”.

The style guide of the Economist, a bastion of liberal reading and another snobby intellectual publication, doesn’t mention how to best use the term; but it does attempt to define it hereExternal link.

Weltwoche, Switzerland’s weekly conservative, says that populism is “a formulaic buzzword” and a “term of abuse for all occasions”.

swissinfo.ch’s style guide has no definition, but one piece of advice: “use sparingly”.

A tale of mis-uses

The term is more often than not associated with right-wing rhetoric and policies, especially now in Europe, where various parties of similar ideologies (but very different policies) have driven a so-called “populist surge”.

Academics, however, are at pains to point out that left-wing populism also exists: it is more usually associated with economic radicalism rather than cultural exclusivity.

Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, a star of democratic politics in the US and a radical left-wing voice, has been mentioned in connection with populism; she has not commented.

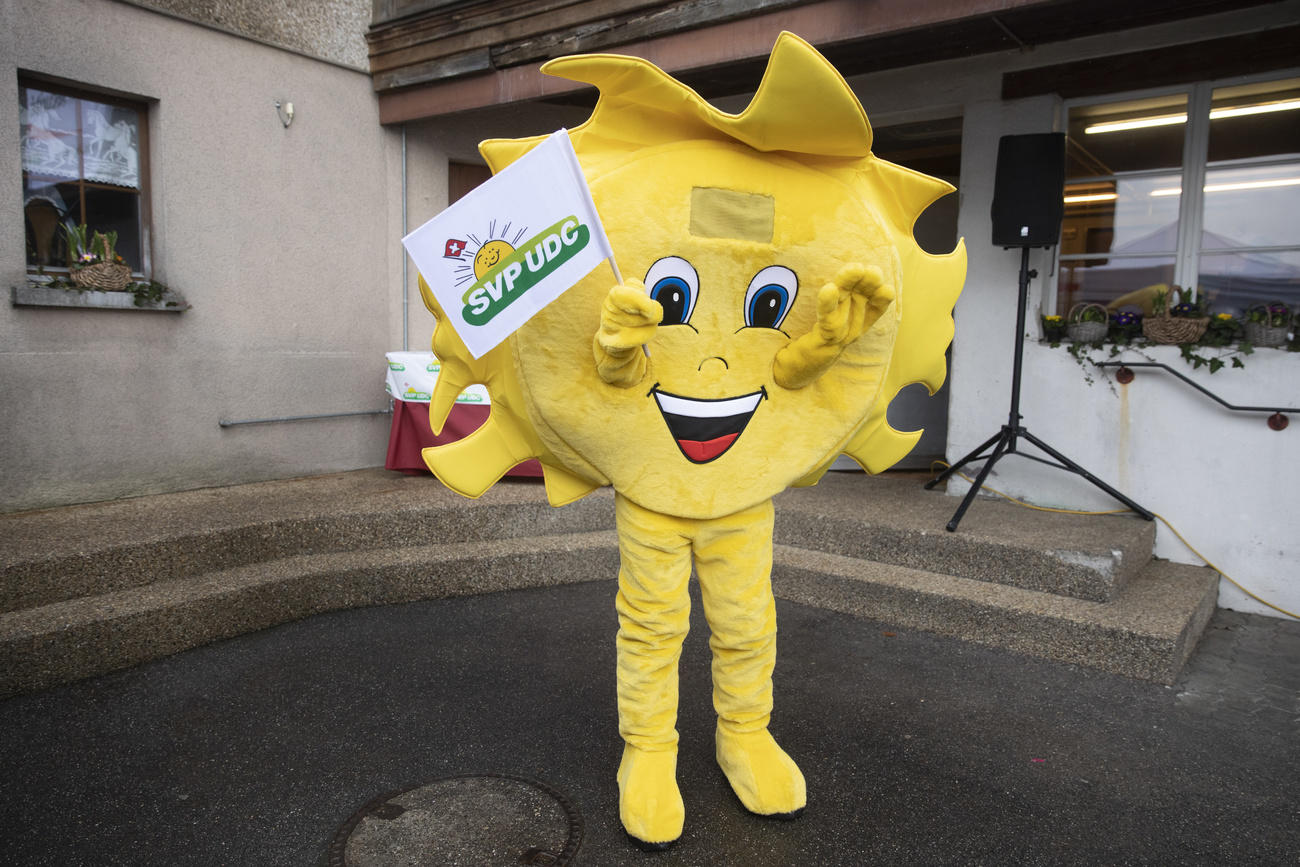

Many academics and journalists say that the Swiss People’s Party is populist, and that their being currently the biggest party in parliament makes Switzerland one of the most populist countries in Europe.

Christoph Blocher, the emblematic figurehead of the People’s Party, told the BBC: “I don’t know what [populism] is”.

An academic study of the 2014 Swiss elections found that there were three main populist parties in the country: the People’s Party, the Ticino League, and the Geneva Citizen’s Movement.

The author of the report, Laurent Bernhard, says that another group not included in the study also deserves a mention: JUSO, the youth wing of the left-wing Social Democrats.

Tamara Funiciello, the outgoing president of JUSO, agrees: “yes, we are populist.”

In Latin, where the term comes from, “populus” means “people” or “nation”.

According to the Economist (again), “widespread use of the term “populism” dates to the 1890s, when America’s Populist movement pitted rural populations and the Democratic Party against the more urban Republicans”.

Google’s Ngram trend viewer, which allows you to search for mentions of specific words in published books from 1800 to 2008, shows the term peaking in 1997.

Google trends, which allows you track internet searches since 2004, has the term “populism” peaking in January 2016, the same month Donald Trump was inaugurated as US president.

Some argue that the very term populism is meaningless when applied to politics, and that over-usage cheapens and detracts from its power to be a legitimate criticism.

Others say that it is a useful term to draw attention to a particular political phenomenon of simplistic messaging and exclusionary ideology currently gaining strength in many countries.

Some argue that the media should not use the term populism at all.

Should it?

More

In Switzerland, populism thrives – but under control

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.