Flu vaccines divide medical community

Despite a high-profile campaign, some health workers are refusing to get vaccinated against current influenza strains and are hesitant to offer the vaccine to patients. Their views present a conflict between public health and personal choice.

“It is very difficult to convince staff – be it in homes for the elderly or hospitals – that they should get themselves vaccinated out of a spirit of collective duty,” explains Claire-Anne Siegrist, the president of the Federal Commission for Vaccinations. A study led by Geneva’s teaching hospitals last year showed that many care personnel thought of seasonal ‘flu as “a benign disease not really requiring any special [prevention] effort.”

Whether to vaccinate against seasonal flu is a perennial question in Switzerland. The Federal Health Office has been running an annual awareness campaign for nine years, targeting people that would run an elevated risk of complications if infected. The campaign also targets people likely to come into contact with at-risk populations.

Giving vaccination priority to those at risk – such as the very young, the elderly and the chronically ill – has been particularly difficult this year because of a nationwide vaccination shortage (see the sidebar for more information).

According to a study carried out by Zurich University on behalf of the Federal Health Office, the vaccination rate of at-risk persons has diminished considerably over the last decade. During the winter of 2006-2007, more than 60 per cent of people over the age of 65 had themselves vaccinated against the flu, but in 2010-2011, fewer than 50 per cent were getting their recommended jabs. The rate of vaccination for care personnel also fell below target.

Of 152 cases of seasonal flu diagnosed throughout Geneva’s university hospitals, 79 developed symptoms after more than 72 hours of hospitalisation. That long delay may indicate that the virus was transmitted via contact with a medical practitioner, a caregiver, a visitor or another infected patient. Just under half of infected patients suffered complications, and in 8.5 per cent of cases, they were severe.

Die-hard opponents

The success of the nationwide vaccination campaign depends on the cooperation of health professionals.

“They are mostly convinced by our message,” says Virginie Masserey, who heads the vaccination section of the Federal Office of Public Health.

“Around 80 per cent of doctors get vaccinated and half of all medical practices regularly take part in the national day of vaccination.”

Yet, some health workers resist going with the flow. Pascal Büchler is a homeopathic physician in Yverdon-les-Bains and a member of a group that offers “nuanced and critical” thoughts on vaccines.

“I’m certainly not a dogmatic anti-vaccinist,” he says. “But vaccines against seasonal flu have been shown to be ineffective for elderly people, who are also the greatest risk group.”

A Swiss-German gynaecologist explained to swissinfo.ch that he refuses to vaccinate pregnant women against influenza, as ordered by the Federal Office of Public Health, “because we cannot rule out the risk of resulting foetal abnormalities”.

Masserey says she can understand this scepticism to some degree on the part of some professionals.

“The vaccines against seasonal influenza vary from 70 to 90 per cent efficiency for adults in good health, and the rate is lower among adults who are at risk of complications,” she says. “Of course we would like to have vaccines that work better.”

Siegrist still thinks a partial level of protection is better than none. “And it’s yet another argument for convincing every person around at-risk populations to get vaccinated”.

Büchler, on the other hand, doesn’t just question the vaccine’s efficiency but also the Federal Office of Public Health’s “alarming” campaign. He points to a large-scale epidemiological study carried out by American researcher Tom Jefferson, which concluded that only five to seven per cent of people displaying flu-like symptoms were actually infected with the virus.

“If we transfer these figures to Switzerland, 75 people would be the accurate figure for deaths caused by influenza, and not 1,500 as the Office for Public Health would have us believe,” Büchler says.

Siegrist rejects that theory out-of-hand.

“The influenza virus is only rarely investigated when we are looking for the cause of a death, for example. Once you take swabs systematically, as Geneva hospitals did, you realise that many complications arise as a result of an influenza infection.”

Economic interests?

Büchler, for one, buys into theories of connivance between the pharmaceutical industry and public health authorities. And public opinion, it seems, has also been swayed.

“The debate and the arguments that surrounded the A(H1N1) influenza virus two years ago have sharpened public mistrust toward the seasonal flu vaccine,” explains Yves Thomas, the head of the National Influenza Centre in Geneva. In 2010, the World Health Organisation was accused of dramatising the worldwide influenza situation, resulting in much higher vaccine sales since many countries had signed contracts with a clause to automatically buy vaccines when the WHO gave the highest alert level.

“A [seasonal influenza] vaccine costs around 10 Swiss francs, when ordered in sufficient quantity,” argues Siegrist. “It is far from being a product which will contribute greatly to pharmaceutical companies profits.”

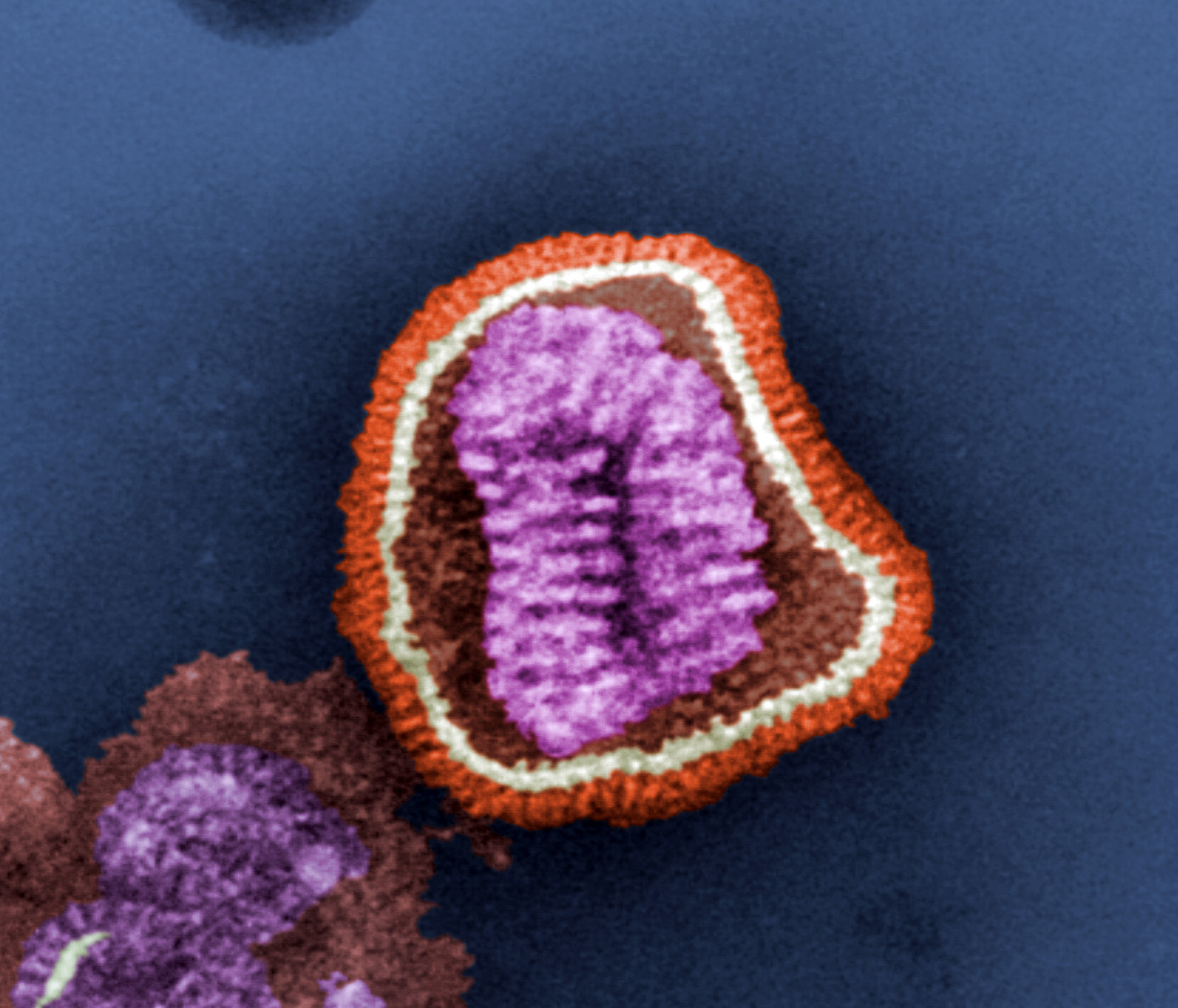

Thomas agrees and points out that influenza vaccines are very labour-intensive to produce and are “complicated, because the vaccine has to be made from scratch every year depending on which influenza strains are prevalent.”

The public might be encouraged to take up the vaccine in greater numbers if there were a single influenza vaccine for life or another method of administering it, but both options remain a long way off.

“You’d need at least 10 years before a universal vaccine gets to market,” estimates Masserey. “The influenza virus does not give lifelong immunity, and it would be very difficult to create a lifelong vaccine. That may well require the addition of adjuvants [substances that enhance the body’s immune response to an antigen] which require several trials to make sure they are harmless.”

One way of putting the brakes virus’s spread is by vaccinating all children, who are the main transmitters of influenza. “In Japan, we saw that this tactic brought down the number of older people who were hospitalised,” says Thomas. It’s an idea that hasn’t been ruled out by the Federal Office of Public Health, but there are considerable obstacles to its implementation, including costs, logistics and public opinion, according to Masserey.

“I don’t think the public is ready to take this step, quite yet,” she says. “And nasal inhalation is a practical way to immunise children, but it is less effective with persons who have already been exposed to the influenza virus.”

Of the 1.3 million doses of flu vaccine ordered by the Swiss government this year, about 400,000 were not able to be delivered on time.

The Dutch manufacturer Crucell was forced to stop all deliveries to Europe due to an internal investigation about a quality problem with two lots.

Close to 160,000 vaccine doses manufactured by Novartis were blocked by federal health authorities because of impurities found in certain lots in Italy.

Following tests carried out by Novartis and Swissmedic, it was established that the vaccines posed no health risk and the delivery ban was lifted on 31 October.

Swissmedic, the Swiss authority for controlling medications and vaccines, specified that the quality control issues were simply precautionary measures and that people who had already been vaccinated in Switzerland “need not fear for their health”.

Swissmedic authorised other vaccine manufacturers to import dosages into Switzerland that were initially intended for the European market. The vaccine should be available before mid-November, ahead of the flu epidemic, which usually doesn’t arrive before December.

When it comes to seasonal influenza and vaccination, Switzerland lies around the European average, both for the vaccination of the general population and that of at-risk groups.

With just 50% of people above the age of 65 vaccinated against the flu in Switzerland, the country remains far from the goal of 75% set by the WHO for 2010. Canada with 70% and the US with 65% are closer to reaching the target.

When it comes to the general population, Switzerland doesn’t have an organised vaccination drive like the USA. 39% of the total American population is vaccinated against seasonal influenza. In Switzerland however, a Zurich university study in 2010-2011 showed that only 19.7 of the whole Swiss population was vaccinated against the flu.

In Switzerland, vaccination against the flu is recommended for elderly people or those suffering from a chronic disease, for those who are undergoing medical care, for women who are more than four months pregnant and for premature children. For these groups, basic obligatory medical insurance will cover the cost of the vaccination.

The Federal Office of Public Health also recommends vaccination for all those who are in contact with high-risk groups: medical professionals, nursery workers, and care workers for elderly people, for example.

As different strains of the virus become more or less prevalent and mutate constantly, vaccines must be repeated every year, between mid-October and mid-November. The vaccine is considered to be effective for between four and six months.

In some hospitals, workers who do not wish to get vaccinated have to wear a protective mask for the duration of any epidemic. Many companies also offer free vaccinations to workers.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.