How Swiss direct democracy made a comeback after authoritarian rule

The Second World War was over when the Swiss government finally started to enjoy the “regime of full powers” that parliament granted them during times of crises. It wasn’t until 1949 – exactly 70 years ago – that the initiative dubbed “Return to direct democracy” passed with a slim margin, bringing Swiss direct democracy back on solid footing.

In times of crises, democracies are sometimes too slow to react. It’s for this reason that the Swiss parliament granted the government the “right to rule” under emergency lawExternal link on the eve of the Second World War. This allowed the Swiss government to make decisions without parliament’s consent, a move that would make it easier for the executive body to act in times of war.

Putting direct democracy on hold

This rule had another side effect. By making ample use of this emergency clause, parliament kept the Swiss people from acting as the third power in democracy alongside government and parliament. The emergency clause deprived voters from rejecting laws using the democratic referendum tool.

With this new rule, the Swiss people could no longer influence the political agenda. The government and parliament, in effect, put Switzerland’s direct democracy system into an artificial coma.

The end of the war in 1945 did not put an end to emergency law. Even though it had already been decided that Switzerland would return to democracy, the process was very slow.

“Patriarchal police state attitude”

The return to direct democracy would have likely taken much longer, if the two initiatives that directly challenged the virtually unlimited power of the seven ministers (see box) had not been submitted in 1946.

The ministers, however, procrastinated. “The government is in no hurry to return to direct democracy,” newspaper headlines read at the time.

The most vehement critic of this emergency law was Zaccaria Giacometti, a constitutional law scholar. He thought the government’s refusal to return to democracy displayed a “patriarchal police state attitude”, which was a sign that Switzerland’s democracy was in a major crisis. The professor went as far as to call the regime illegal.

This criticism was voiced by the constitutional law professor, Hans Nawiaski who had fled Germany in 1943.

According to Zurich constitutional law professor Andreas Kley, his criticism was not unfounded. “The government was the creator of the constitution as well as the legislative and regulatory authority and was no longer bound by the Swiss constitution. It was allowed to impose emergency laws within the competences of the cantons and did not have to observe civil liberties.”

Two people’s initiatives were launched to reintroduce direct democracy.

When in 1949 people and cantons voted in favour of the first initiative, government and parliament were shocked. The second initiative was withdrawn. The indirect counterproposal to this second initiative was that the emergency law regime was not abolished until 1952.

The crisis of democracy in Switzerland and elsewhere did not just start with the sabre-rattling that was happening in Germany at that time. After the stock market crash in 1929, anti-democracy voices became louder in Switzerland and throughout Europe. They called for democracies to have less power, arguing that it hampered reasonable governing in times of crisis.

Despisers of parliamentarianism

There are historical roots for the reticence to return to direct democracy. In the 1930s, Switzerland’s leading thinkers had already developed what is known as the political-cultural movement of “spiritual national defenceExternal link”. This Swiss obsession to safeguard national identity was supposed to counteract the National Socialist threat posed by Hitler’s ideology of “blood and soil”.

The spiritual national defence was associated with the image of the brave and powerful Swiss who swung morning stars and halberds, two classic war weapons of the Swiss mercenary army in the Middle Ages.

However, some believed democracy weakened this image.

Swiss Nazis and government ministers

In Switzerland, this attitude was most commonly in radical forms among Swiss Nazi sympathisers and fascists. They mocked the democratically elected parliament and called it a lame “talking shop”.

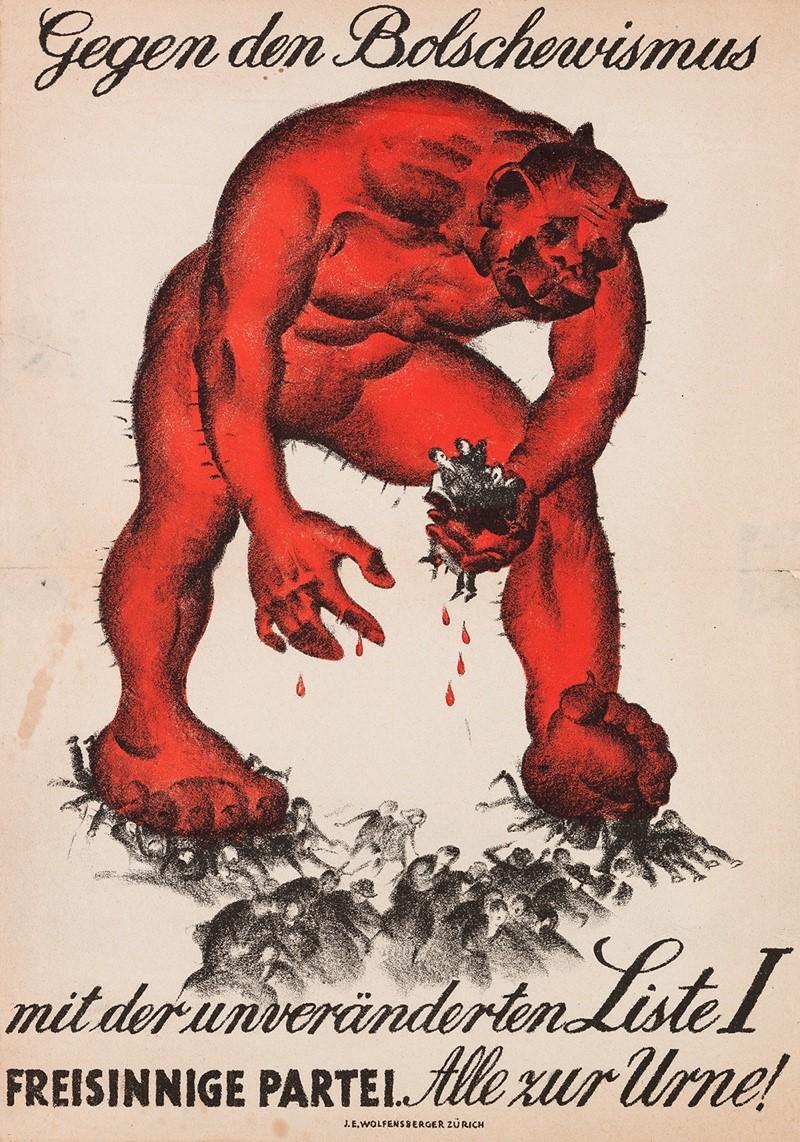

However, people outside right-wing extremist circles were also convinced that the democratic model had many weaknesses. During the interwar period and after the General Strike, political lobbying groups started to use new marketing methods. Their aim was to create an image of a political enemy who could no longer be dealt with by democratic means. It was the image of the Jewish-Bolshevik conspirator.

Many saw a solution in the so-called corporatist formsExternal link of government, whereby corporative professional organisations similar to guilds and fraternities should replace parliaments. The state, however, would be governed by strong leadership or a strong leader.

These federal corporations were only supposed to play an advisory role to the autocratic leadership. Even the government shared such strong anti-democratic beliefs.

Democracy on the verge

The tendency towards authoritarian forms of government survived the war, and the government and parliament were still against the return of the referendum democracy.

The Catholic-conservative parliamentarian Karl Wick said in 1948 that it was possible for a state to “democratise itself to death”: “Democracy is important; however, the internal and external security of a state is more important.”

Only a few parliamentarians were in favour of the two popular initiatives for the reintroduction of direct democracy. Senior trade union official and Finance Minister Max Weber was one of them: “It’s impossible to fight the danger of a dictatorship and undemocratic measures by limiting democracy,” the Social Democratic minister said.

Odd Alliances: the Ligue Vaudoise

However, the reflexes of direct democracy could still be felt. The primary incentive came with a popular initiative dubbed “Return to direct democracy”. Ironically, its initiators were not flawless democrats. On the contrary, some of the most dedicated among the initiators consisted of members of an organisation called Ligue VaudoiseExternal link.

Originally, the Ligue was a cross-party protest movement from French-speaking canton Vaud. It was founded in 1933 and aimed at stopping the introduction of cantonal taxes on local wines.

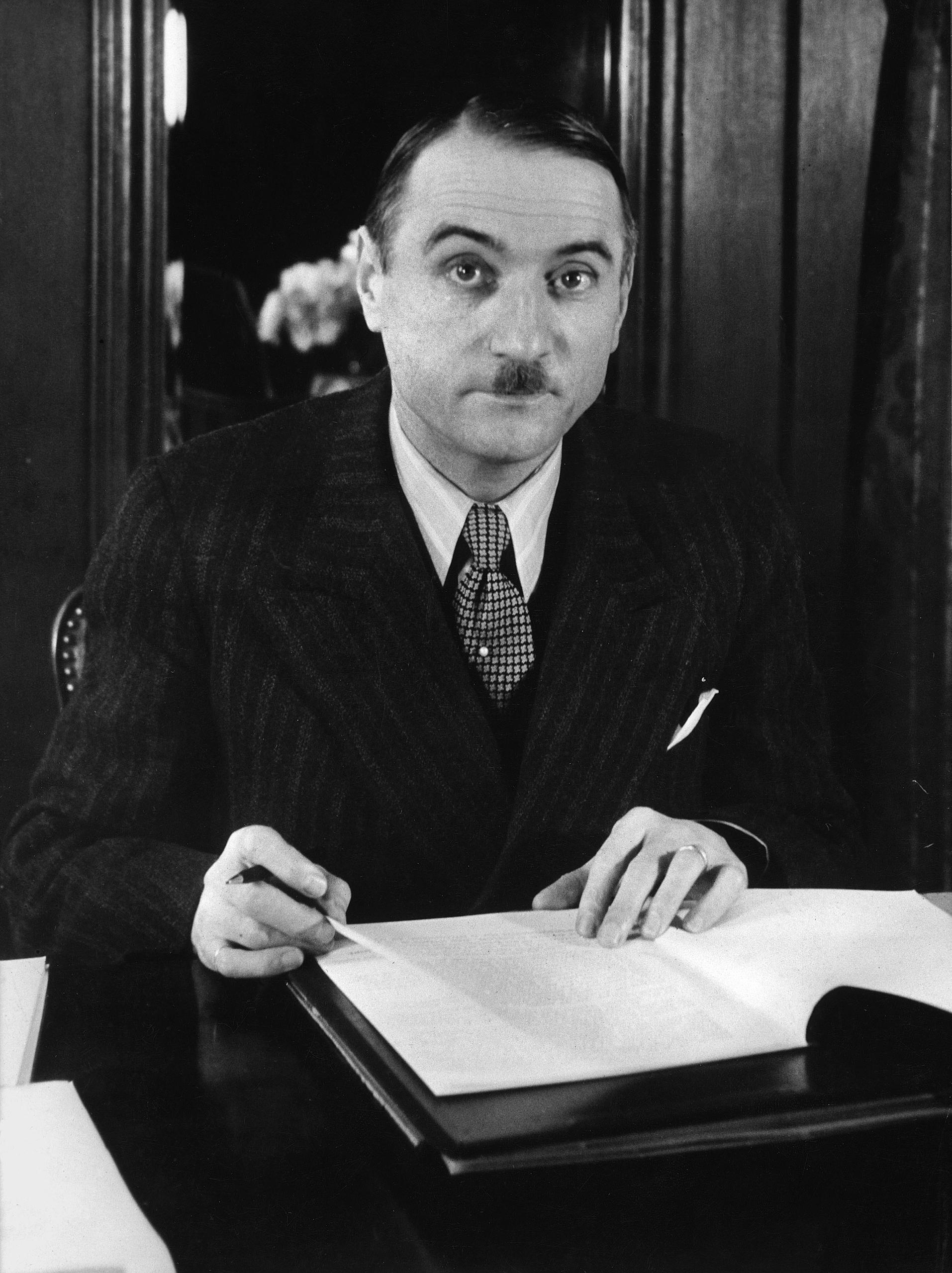

It was anti-centralist and anti-state. The founder and co-initiator was the Swiss essayist and journalist Marcel Regamey. He loathed democracy, and in 1944 he even lamented the downfall of the Third Reich. He thought that “liberating industry from the grip of international Jewish capitalism” and unifying all European countries under one flag was “defensible”.

At the end of the day, the fathers of the initiative promoted the spirit they were fighting against. The paradox is that it was actually the anti-democrats who sowed the seeds and helped Swiss direct democracy emerge from its coma.

More

What’s a referendum?

More

What’s a people’s or citizens’ initiative?

Adapted from German by Billi Bierling

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.