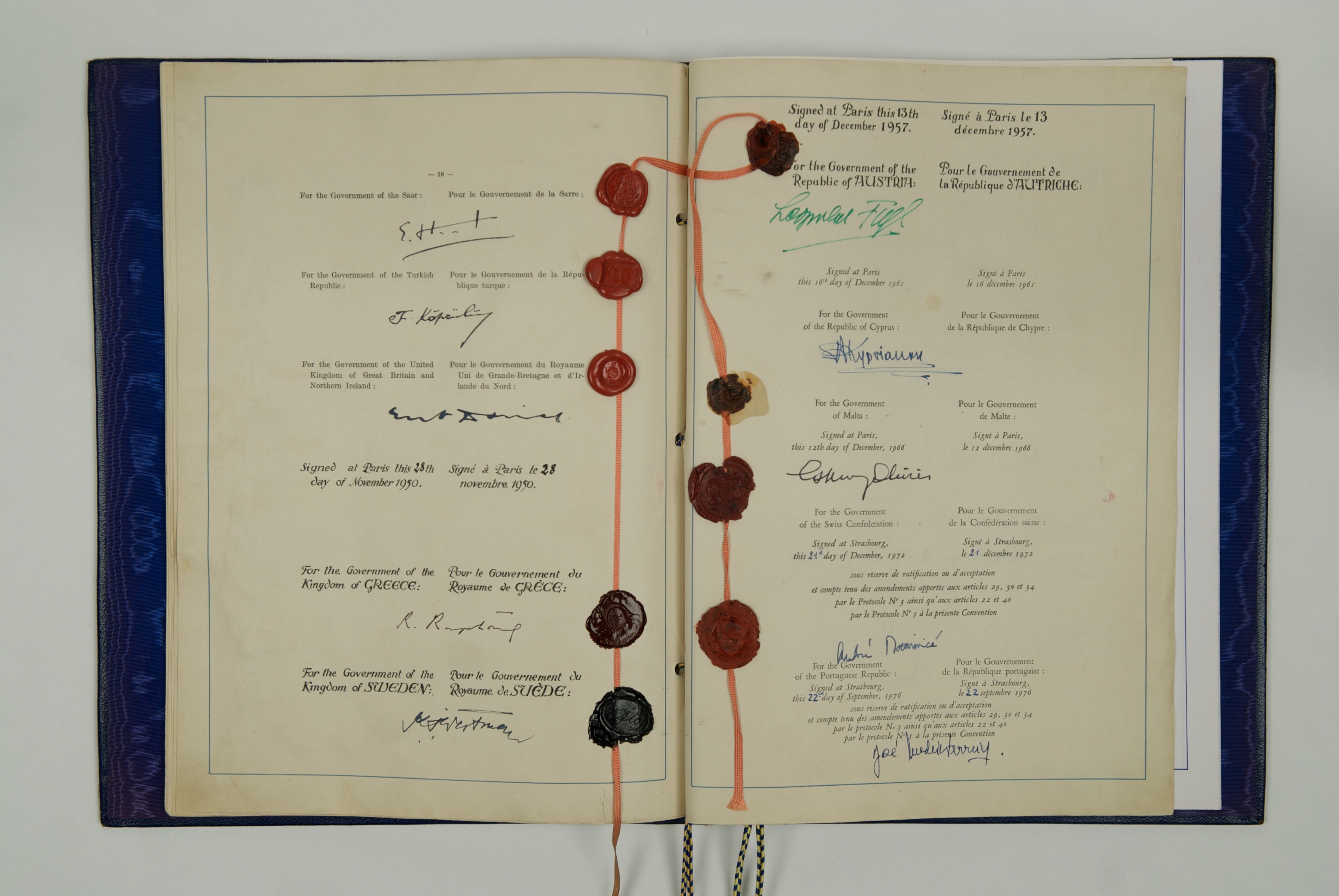

Happy anniversary? Switzerland marks 50 years at the ECHR

Half a century after Switzerland ratified the European Convention on Human Rights, the treaty and its Strasbourg court face pressure across Europe.

Over the past 50 years, the European Convention on Human RightsExternal link has not always been a daily conversation topic for most Swiss. But in 2024, as if to mark the golden anniversary of ratification, it enjoyed sudden notoriety. In April, after the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) – which upholds the Convention – ruled in favour of a group of older women who claimed Swiss climate policy infringed their rights, debates flared. For some, it was a trailblazing example of climate justice; for others, including parliament, it was judicial activism.

Has the attention raised the profile of the ECHR? “In theory yes, in practice no,” says Evelyne Schmid from the University of Lausanne. Such a case could raise awareness of how the Court and the Convention workExternal link, or how human rights law interacts with environmental questionsExternal link, she says. In reality, things quickly turn polemical. “Narratives about foreign judges and the perceived struggle between direct democracy and international law get more clicks than sober discussion of a complex verdictExternal link,” she says.

For Schmid, strong reactions were to be expected. “Climate issues are sensitive – they relate to fundamental aspects of society and concern us all”, she says. The Swiss are also used to antagonistic debates about the ECHR, especially after a (failed) 2018 initiative to downgrade its legal standing. And as Schmid writes in a forthcoming articleExternal link, the past 50 years have been marked by an ambivalent attitude: while authorities, federal judges, and most parliamentarians have been largely open to the court, opponents have sometimes questioned why the country – an apparent “model pupil” on human rights – needs it at all.

More

Seven ways the ECHR has shaped Swiss law over the years

Critical compliance to open defiance?

What did however surprise Schmid was the response of authorities to the ruling. In August, the government brusquely batted it back to Strasbourg, saying Switzerland is on track to meet its climate obligations. This is difficult to prove exactly. But for Schmid, it was striking that the government made no explicit commitment to the binding nature of ECHR verdicts. In the past, the stance was often “criticise but comply”, she says. Now, defiance was more brazen.

This mirrors wider problems of legitimacy for the ECHR across Europe in recent years. With a “backlash against international courtsExternal link” in general, and with war on the agenda, the Council of Europe – the 46-member organisation to which the ECHR is affiliated – is facing tough times.

The most obvious challenge is Russia. For at least a decade, Moscow had been routinely reprimanded by the ECHR for human rights violations, including in high-profile cases involving late opposition figure Alexi Navalny. In March 2022, after its invasion of Ukraine, Russia then became only the second-ever state to be expelled from the Council of Europe – the first was Greece under military dictatorship in the 1970s. Thousands of cases are still pending against Russia; judges are working through them, but as ties to Moscow are cut, there’s little hope of having an impact.

Pushback

There have also been less violent cases. In 2021, Polish judges issued a controversial rulingExternal link that the ECHR was partly incompatible with the country’s constitution. Adam Ploszka, from the University of Warsaw, says this came after years in which the right-wing government had engaged in a “hostile takeover” of the judiciary, filling posts with regime-loyal officials. “Attacking the constitutional legitimacy of the ECHR was a way to justify internationally the policy of not adhering to ECHR judgments,” Ploszka says.

Such reforms can then be hard to reverse. When a new coalition government took power in Poland in December 2023, it immediately made a clear commitment to the ECHR. However, Ploszka says, there has not yet been major changes in how the national judiciary is organised. “The intention [of the new government] is clear,” he says. But the reality is hampered by various factors, including the Polish president’s veto power.

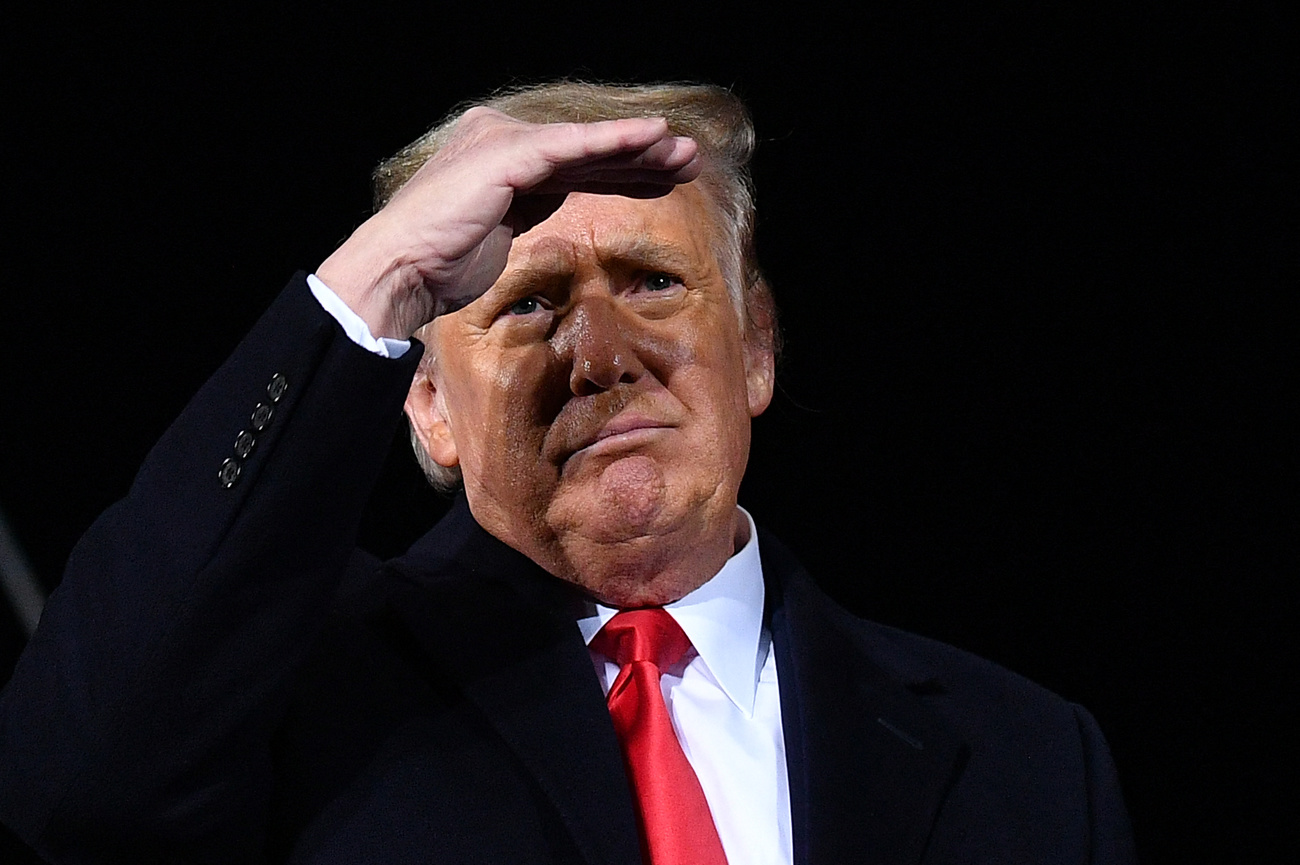

It’s not just member states from post-Communist Europe which have had run-ins with Strasbourg. Last year, France flouted an interim measureExternal link by the court in order to deport a suspected radical Islamist to Uzbekistan. The UK, despite its strong human rights record (see chart), has also had issues. In June 2022, after an interim order to stop the UK sending asylum seekers to Rwanda, then-British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak vowed that “no foreign court will stop us from getting flights off” – before a domestic court derailed his plans anyway.

Calls for reform

Sunak (who called the Swiss climate verdict “complete overreach”) and some of his Tory predecessors even mooted leaving the ECHR altogether. And while this is an extreme option, it can also feed pressure from more moderate conservative voices. Earlier this year, a Financial Times writer suggested that the court needs to “save itself from itselfExternal link” and “find ways not to add to pressures on mainstream governments”. This could include “narrowing its remit” – an idea also raised in the Swiss parliament by a centre-right motion calling for the court to refocus on its “core tasks”External link.

Is reform needed? Ploszka says such calls overlook the fact that the court has already been adapting – and narrowing its remit. In particular, he says, a 2021 protocol to the Convention reinforced two key doctrines: the principle of subsidiarity – which says national states are the main responsible parties for protecting human rights – and the “margin of appreciation”, which offers countries room for manoeuvre in how to fulfil obligations.

Kanstantsin Dzehtsiarou from the University of Liverpool agrees and says ECHR judges have recently become more “cautious” in their interpretations. Whether as a consequence of the new protocol, or of the general rise in human-rights-critical rhetoric from many states, judges don’t want to antagonise, he says.

Setting limits

For Dzehtsiarou, the April 2024 Swiss climate verdict was a rare example of the court pushing the envelope. He is moderately critical of it; the current ECHR set-up is not optimally designed to rule on climate change cases, he says. Yet once the complaint landed on its table, judges “could hardly ignore one of the most fundamental challenges to human rights of our time”. The final ruling, for Dzehtsiarou, amounts to an effort by the court to “get a foot in the [climate] door” while still offering Switzerland as much freedom as possible in how to implement it.

Other reform ideas include continuing to tackle the ECHR’s case backlog, which fell from 160,000 to 67,000 over the past decade. The question of complaints by associations also needs attention, Dzehtsiarou says; should cases brought by groups not directly victims of a violation – like the Swiss older ladies – be admissible? Other ideas about focussing on “core tasks” are however tricky. What exactly are these core tasks? And to what extent would they mean ditching the notion of the Convention as an “living instrumentExternal link”? New developments – in communications or science, for example – have to be considered if courts are not to become completely irrelevant, Dzehtsiarou says.

Ultimately, as the Council of Europe’s 2023 Reykjavík DeclarationExternal link makes clear, the question of climate change isn’t going away. Whether the Swiss ruling will provoke a backlash among member states against the ECHR remains to be seen. But when it comes to calls to limit the scope of the court, Switzerland has to remember it “cannot single-handedly change the Convention”, Dzehtsiarou says. Any new protocol would need the agreement of all 46 member states – even in the current political climate, a hard task.

Edited by Balz Rigendinger/ac; image research by Vera Leysinger

More

What happens when victims cannot get legal remedy in Swiss courts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.