How America shaped Geneva’s international role

After the First World War, American leaders regarded Geneva as a city on a par with Jerusalem or Rome. The Swiss city first gained attention as a centre for international law thanks to an American warship – the Alabama.

International Geneva would likely not be what it is today without the United States. Its rise as a city of international organisations was buoyed by admiration and advocacy from across the Atlantic.

American enthusiasm for Geneva as a city, but most of all as an idea, reached its peak after the First World War. Geneva was now on a par with Jerusalem, Athens, Rome and Constantinople, declared National Geographic in 1919. The city, the magazine added, could become “the centre of the moral universe of mankind” as the new seat of the League of Nations.

George Washington and the Geneva Academy

The recurring American fascination with Geneva goes back to the time when the US was founded in the 1770s. Some of the founding fathers were admirers of Geneva philosophers and exponents of natural law. These Protestant men went so far as to draw up plans to transplant the Academy – today the University of Geneva – with its entire faculty from Geneva to be a federal university in the new American republic. The religious connection was decisive. Geneva had the function of “cultural capital of French-speaking Protestantism”, as the Historical Dictionary of SwitzerlandExternal link puts it.

Thomas Jefferson, in whose mind this “idea had aroused a lively interest”, backed the idea with determination. One of the aims was to remove the Geneva scholars from the threat of Robespierre’s terror in revolutionary France in the1790s. The first US President, George Washington, was even prepared, as he wrote in a letter to Jefferson, to invest money from his personal fortune in this project. But the idea failed.

More

How Switzerland became Switzerland: the main chapters of the country’s history up to 1848

The Alabama arbitration between the US and Britain

By 1872 the issue was no longer to transplant Geneva to the US. Rather, Geneva was now convenient as a neutral ground between the great powers. It also suited the American political establishment that they shared a range of liberal beliefs with the “Republic of Switzerland”.

At that time Geneva was the biggest city in Switzerland. Its reputation as a venue for international organisations was just emerging. This was a few years after the drafting of the first Geneva Convention – an international treaty protecting the casualties of war and recognising the role played by the Red Cross. It had been signed in 1864 in the same room at Geneva city hall where in 1872 the court of arbitration on the Alabama was held. Ever since, it has been known as the Salle de l’Alabama (Alabama Room).

The name Alabama hardly makes anyone think of Geneva today. But this was the first modern, international tribunal not held under the aegis of a king or emperor. It was not, of course, named after the southern US state, but after a warship.

During the American Civil War from 1861 to 1865, the British supplied both sides with arms. This was legally and diplomatically allowed – even though the Union side did not like it. Britain could be accused of hypocrisy here, because the British had themselves already outlawed slavery.

Yet the British had subverted their own declared neutrality when they sold warships to the southern states through various channels. These warships inflicted heavy damage to the northern side – and the most destructive of them was the Alabama.

More

Sister republics: what the US and Switzerland have in common

After the eventual victory of the Union side, the northern states concluded an agreement with Great Britain, which provided that an international court of arbitration, whose decision would be binding, should decide on matters of responsibility and reparations. In the end the British had to pay out $15.5 million (CHF14 million).

Jakob Stämpfli, ‘stubborn as a mule’

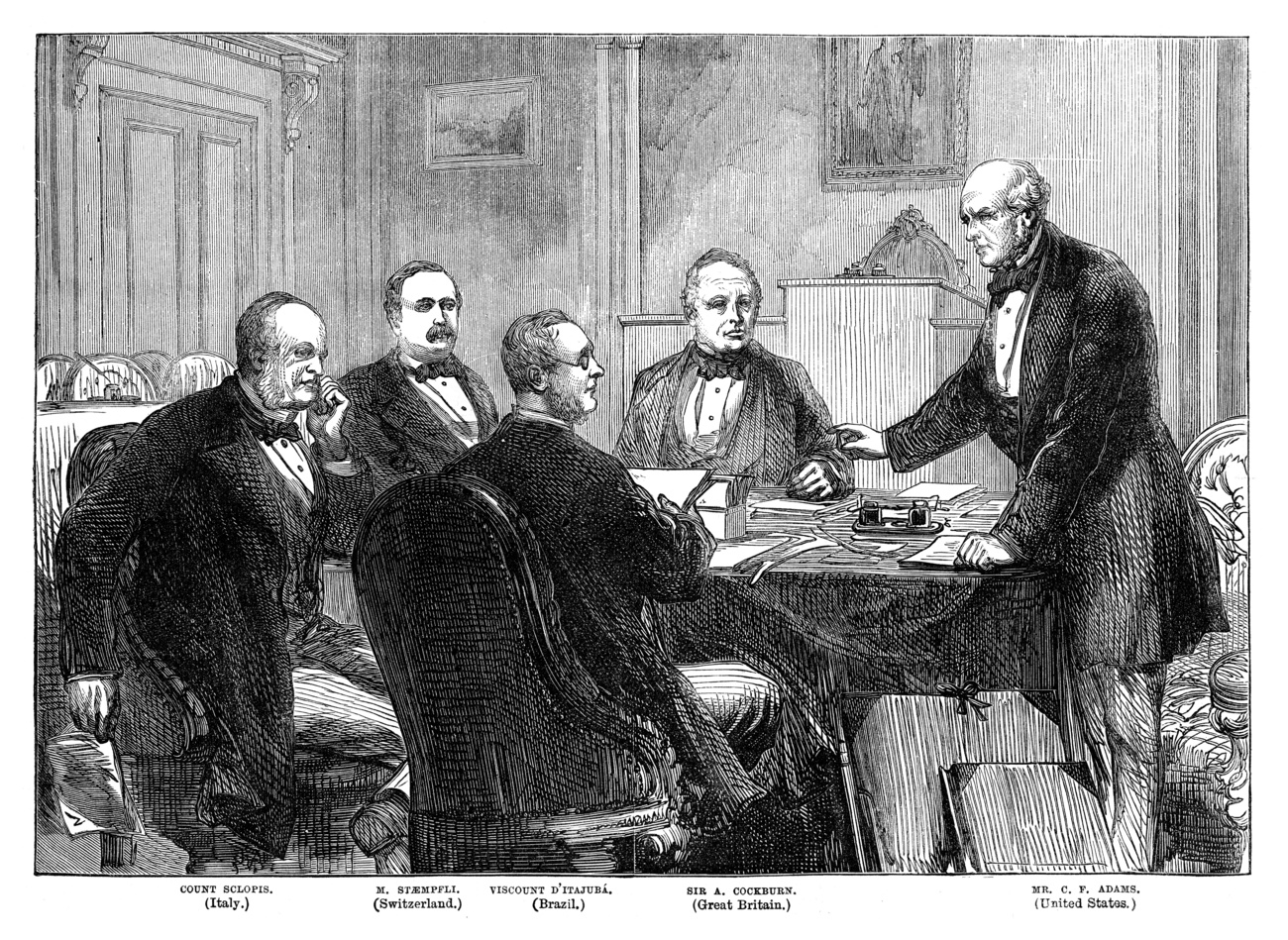

Alexander Cockburn, the British representative on the Alabama tribunal, was dissatisfied not only with the outcome, but with his fellow judges on the panel. He described the Swiss Jakob Stämpfli – a former Swiss government minister – as “a fanatical republican who has nothing but contempt for monarchical governments and their ministers; he is as ignorant as an ass, and as stubborn as a mule”.

Besides Stämpfli and Cockburn, the panel had, of course, a representative from the US, as well as a Brazilian and an Italian. “I quickly realised,” wrote the Italian Frederic Sclopis, who was the president of the arbitration panel, “that our discussions needed an environment that was favourable.” This was provided by Geneva, where they found “a strong spirit of liberty” coupled with “respect for law and order”.

Cockburn – a hothead, according to all sources – also had few nice words to say about Sclopis. But Cockburn had a particular animus for Stämpfli, who managed to push through his own plan for decision-making. Stämpfli, whose memories of the brief civil war that preceded the foundation of the modern Swiss republic in 1848 were still fresh, threw his support behind the US. When the court’s decision was announced, Cockburn was red in the face and had tears in his eyes, according to a report by the American representative.

Cockburn wrote a dissenting opinion of 250 pages, a document that reportedly caused shock with its aggressive style.

Success of the Alabama arbitration

The satisfactory result of the Alabama arbitration became an issue in the next American election. It was less of a talking point in Britain, where the Liberals lost their majority in parliament in the 1874 general election.

“Contemporary public opinion was impressed by the success achieved by the arbitration process,” says Geneva historian Ladislas Mysyrowicz. He calls the tribunal a “milestone in the development of international jurisprudence”. The result, James H. Hutson wrote in The Sister Republics, “raised hopes that a mechanism might be found to heal the world’s nations of their mad bellicosity.” Geneva and Switzerland were seen as an oasis of hope.

Woodrow Wilson and the League of Nations

This was only the beginning of such optimism about a lasting peace. Half a century later, US President Woodrow Wilson adopted the League of Nations as his prestige project. This was to be an international organisation of world powers to prevent anything like the Great War from happening again.

In discussions after the First World War, it became clear that the League of Nations should have its headquarters in a neutral European state. Apart from Geneva, Brussels was initially favoured in 1919. In Geneva, the presence of the Red Cross and the Alabama arbitration were highlighted as the main arguments, other than practical considerations, for choosing Geneva. Some historians say that Wilson – himself a Presbyterian – had a certain sympathy for the city of the reformer Calvin. Other say that Wilson preferred Geneva because the seat of the League of Nations belonged to none of the existing alliances.

Swiss lobbying of the Sister Republic

Switzerland had been neutral in the Great War – but not without some controversy. The country was regarded by the US government in particular as a haven for spies, by which they meant Bolsheviks like Lenin and other socialists. The American consul at the time noted that German-speaking Switzerland was sympathetic to Germany. Despite such criticism, Wilson saw fit to appeal to the “common ideals of warm friendship” uniting Switzerland and the US.

From 1918 on, Swiss foreign minister Felix Calonder increasingly adopted Wilson’s rhetoric about the League of Nations. The Liberal politician told the Swiss parliament that international law was essential for a small state if it was not to be at the mercy of power politics.

By the end of the Great War, Switzerland was making strenuous efforts to prove its neutrality. Once the German Empire capitulated, the country embarked on some intensive lobbying. The Swiss government was now eager to host the League of Nations. In Switzerland people were proud of their friendship “with the great sister republic”, foreign minister Calonder wrote in October 1918 to the Wilson administration. Switzerland believed, he said, in the League of Nations as an instrument of world peace. To ensure world peace, the League of Nations would have to use economic sanctions and have a military force of its own.

The US prevailed and the League of Nations duly arrived in Geneva – and with it hope, but also a great sense of responsibility. Even a rather euphoric article in National Geographic in 1919 left future outcomes open: “Geneva will be the wellspring of the noblest triumph or the greatest failure in the history of human endeavour.”

Failure of the League of Nations

The US did not join the League of Nations. Wilson’s international framework failed to convince people at home. In Switzerland, public opinion was more favourable. In a national referendum in 1920 on joining the League, farmers’ lobbyist Ernst Laur, who belonged to the predecessor party of the right-wing Swiss People’s Party, campaigned heavily in favour of the League of Nations. This is said to have been decisive.

The League of Nations itself turned out to be a failure. In the course of the Second World War, Europe in general and Geneva in particular lost its long-standing claim to hosting international organisations. The latter set up secretariats across the Atlantic. In the Geneva League of Nations secretariat there remained only a skeleton staff – for fear of the Germans marching into Switzerland at any moment.

Once the war ended, it was now the turn of the United Nations, headquartered in New York but with its European seat in Geneva. Many years passed until Switzerland itself joined the new organisation. In fact, it only happened in 2002.

Edited by David Eugster

Adapted from German by Terence MacNamee/gw

Fleury, Antoine: L’enjeu du choix de Genève comme siège de la Société des Nations, 1981.

Herren, Madeleine: Internationale Organisationen seit 1865. Eine Globalgeschichte der internationalen Ordnung, 2009.

Hutson, James H.: The Sister Republics. Switzerland and the United States from 1776 to the Present, 1991.

Mysyrowicz, Ladislas: The Alabama Arbitration Geneva 1872, 2004.

Weber, Florian: Die amerikanische Verheissung, Schweizer Aussenpolitik im Wirtschaftskrieg 1917/18, 2016.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.