How counterspeech is tackling hate speech in 2025

Hate speech is considered a growing threat to society and democracy. As Facebook and Instagram relax content restrictions on their platforms, the commitment of volunteers who push back against hate – with so-called counterspeech – is becoming more crucial than ever.

“The people who spread hate speech are very well organised,” says Anne-Céline Machet. They talk to each other and pool their energies. As the director of a feminist foundation in Geneva, Machet is worried by this. She notes that women are already taught as children to be discreet and not take up too much space, a dynamic that is amplified on the internet.

The online hate directed at female politicians or journalists – along with the indirect impact on all women who witness it – poses a threat to democracy, she says. One consequence is that women no longer participate in public discourse. “Some who have come into the spotlight have since withdrawn from the public sphere,” Machet laments. Preventing this is essential, she says, emphasising the importance of education and raising awareness. “We must make clear that it’s possible to take action against hate speech.”

What is hate speech?

Hate speech refers to insults and derogatory statements which target a person based on their membership of a social group.

A 2022 study by Sotomo found that 86% of the Swiss population consider digital violence to be very or somewhat widespread. The issue extends far beyond Switzerland. It is a global problem, and awareness of it is growing accordingly. The Council of Europe describes hate speech as a “serious threat” to “the cohesion of a democratic society” and warns that, if left unchecked, it can fuel physical violence and conflict.

In 2023 a UNESCO study conducted in 16 countries found that 67% of respondents frequently encountered hate speech online. The figure was lower in Western countries such as Belgium, Austria and the US; it was significantly higher in Indonesia, Bangladesh and India.

According to respondents in all countries, certain groups are particularly targeted by hate speech, including LGBTQ+ people, ethnic minorities, migrants and women.

A pre-emptive strategy

“We want to make the internet safe again for women and gender minorities – at least within the scope of our project,” Machet says. Months before launching its online campaign on International Women’s Day on March 8, the Fondation pour l’égalité de genre (foundation for gender equality) has already developed a strategy to counter the anticipated wave of hate speech.

Machet and her colleagues have been supported by the Swiss project Stop Hate Speech. “Many people are ready to respond with positive comments,” Machet says. “We also document, report and safeguard against instances of hate speech.”

The issue of online hate speech is of widespread concern in 2025. In mid-January, shortly before US President Donald Trump took office, Mark Zuckerberg stunned many by announcing that Facebook and Instagram would give more priority to freedom of speech – therefore taking a more lenient stance on hate speech. Instead of relying on moderation by trained staff, the platforms will now depend on volunteers who flag and respond to potentially harmful content.

More

Why some people turn to authoritarianism in the name of freedom

At this stage, it remains unclear what consequences this will have on how people use and engage with social media. But many are now asking whether online spaces will become even more hostile.

Standing up to hate speech

Major platforms such as TikTok, Facebook and Instagram dominate the digital world. Yet the most promising approach to combating hate may lie in smaller, more focused efforts: in networks and messenger groups where people coordinate responses to hate speech, using what is known as counterspeech.

According to Stop Hate Speech, around 1% of all online accounts are responsible for 65% of hate speech on the internet. This figure also offers hope, which can be felt at Stop Hate Speech workshops. If only a few people generate the bulk of hateful content, it only takes a few to stand up to them. Importantly, countering hate speech does not mean responding with aggression, but rather calling it out for what it is.

Sophie Achermann is the founder of the Stop Hate Speech project. In 2015, while serving as a youth delegate for Switzerland at the UN in New York, she organised a workshop on sexism on the internet. “That was before the #MeToo movement,” Achermann recalls. “The room was packed and there was a lot of interest in the problem. We felt we were ahead of our time back then.”

Some people downplayed the problem, advising those affected by online violence to ignore hateful comments or simply turn off their phones, she says. But in today’s digital world, this is no longer a viable option, she adds.

Who sets the rules?

A lot has changed since then – including the feasibility of certain solutions, Achermann says. The original idea was to use an algorithm to scan social networks for hate speech. However, after the first election of Trump in 2016, criticism of Facebook’s role in spreading harmful content intensified, making such an approach no longer viable. Today, the major social media platforms are no longer freely searchable.

Some forms of hate speech are prosecutable under criminal law. For example, cases of personal defamation or violations under the European Union’s Digital Services Act. But Achermann is convinced that criminal law alone cannot eliminate the problem.

A 2021 studyExternal link by Stop Hate Speech and the federal technology institute ETH Zurich in 2021 reached a similar conclusion. While the “rise of online hate speech has been accompanied by efforts to curb it”, the study notes that government and social media moderation policies “may suppress valuable as well as illicit speech and disperse rather than reduce hate speech”. It said international organisations and civil society organisations were increasingly turning to counterspeech as a strategy to confront hate speech.

Since then, power has become more concentrated, and the ties between authoritarian governments and major tech companies have grown stronger. Elon Musk, owner of X (formerly Twitter), has publicly expressed admiration for Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who has been accused of anti-Muslim hate speech by both political opponents and independent observers. In Modi’s India, where freedom of the press is increasingly restricted, content moderation could become a tool of repression rather than protection.

‘Empathy treatment’ shows results

The 2021 ETH Zurich study, “Empathy-based counterspeech can reduce racist hate speech in a social media field experiment”, has been read more than 30,000 times, which is considered a runaway success for an academic paper. In it, scientists analysed more than 1,000 English-language X accounts that appeared to be operated by real people and contained tweets with hate speech.

The X profiles were divided into five groups. One served as a control group, while others received responses from researcher-created accounts which engaged in either a neutral apolitical way, with humour, by referencing potential consequences, or with an appeal to empathy.

The experiment showed that humorous animal memes had no effect, nor did reminding users that their tweet was publicly visible to family members or employers. However, responses that used empathy did have an impact. For instance, one read, “for African-Americans, it’s really hurtful to see people use language like this”.

The impact was “consistent, albeit relatively small”. Those who received the empathy treatment posted fewer xenophobic tweets, reduced their overall posting activity, and were more likely to delete their original hate speech.

Opponents of content moderation prefer counterspeech

The Future of Free Speech thinktank at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee cites the ETH Zurich study in its Counterspeech Toolkit.

Even major critics of content moderation – who place a high value on freedom of speech – support counterspeech strategies. In a 2023 collection of works on the topic, Jacob Mchangama and Natalie Alkiviadou from The Future of Free Speech argued that “content moderation which censors” has often harmed dissidents in Syria and Afghanistan who were resisting official propaganda.

More

Digital citizens could shake up democracy in Switzerland and beyond

According to Mchangama and Alkiviadou, YouTube’s automated content moderation resulted in the removal of thousands of videos filmed by opposition activists which were documenting the Syrian civil war. Similarly, they warned that if the EU wants “what’s illegal offline to be illegal online”, this would undermine the efforts of LGBTQ+ people in Hungary, where there is an anti-LGBTQ+ law, or religious critics in Spain, where blasphemy is a punishable offence.

For Mchangama and Alkiviadou, counterspeech is the only viable approach to countering hate on the internet.

30,000 comments in one month

Sophie Achermann, from the Stop Hate Speech project, and the Public Discourse Foundation that emerged from it now work with major Swiss media outlets to monitor and analyse online comments. They once came across an account that had posted 30,000 comments in one month. “We were all convinced that it couldn’t be a real person,” Achermann says. “But it was.”

Achermann and her team use their findings to advise organisations that could be affected by online hate speech, such as Geneva’s gender equality office. Their aim is to create a trickle-down effect. “We want to motivate people, who aren’t politicians with 100,000 followers, to take action,” she says.

“We don’t need a huge number of people to drown out the 1% responsible for 65% of online hate speech.”

Collective effort

The work of the Stop Hate Speech initiative also involves teaching those affected by hate speech how to minimise its negative effects. One key principle is that people directly targeted by hate speech should not be the ones responding with counterspeech. This is because, for them, the psychological burden of confronting hate speech and its perpetrators is disproportionately high.

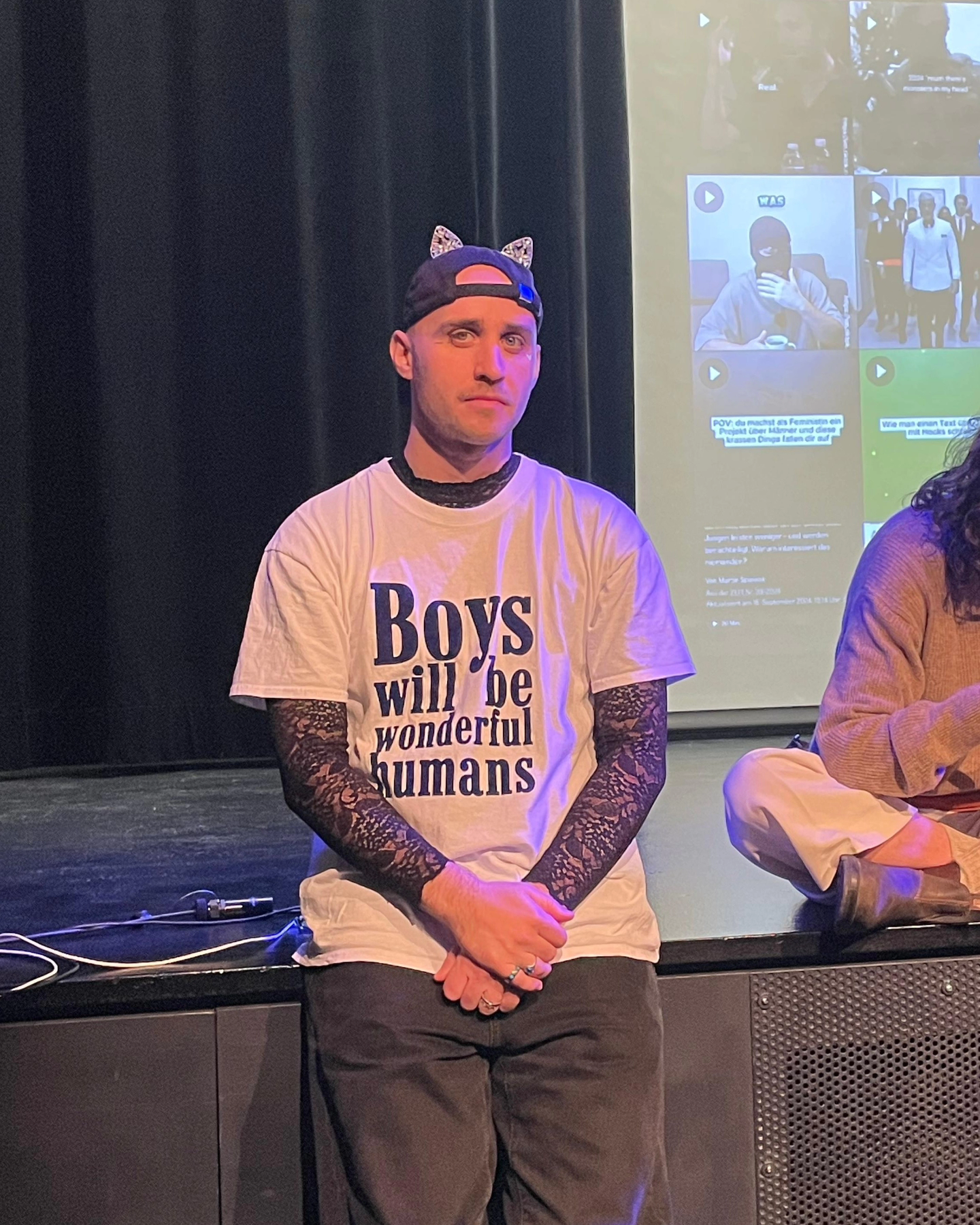

Inspired by Stop Hate Speech, Caspar Weimann coordinates chat groups from northern Germany with people who respond to hate speech. “If someone posts a link to a thread which requires a response, we have a broad network of artists and professionals in the culture sector who help shape the conversation,” Weimann says. The network is expanding thanks to seminars that Weimann and colleagues organise.

“I respond to misogynistic hate speech,” Weimann says. “But if it becomes transphobic, I post it in the group and ask others to respond.” Weimann wears a hat labelled “God is trans” during the interview.

Huge corporations and spaces for interaction

Weimann was recently involved in a performance project on TikTok, where clips styled after masculinity coaching videos sought to reach young men at risk of becoming radicalised and misogynistic. The videos, which promote vulnerability and emotional awareness, have been viewed millions of times and shared thousands of times. Weimann believes it is crucial that artists do not abandon these platforms but rather occupy and use them.

According to Weimann, “huge corporations that can be incredibly dangerous” are behind social media, but at the same time they provide “spaces of social interaction which shape our democracy”.

When asked how many people are in the counterspeech chat groups, Weimann checks a mobile phone. “Let’s see. There are 250 on WhatsApp and 95 on Signal.” That’s how few people it takes to make a substantial difference using counterspeech.

More

Our democracy newsletter

Edited by Mark Livingston. Adapted from German by David Kelso Kaufher/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.