Learning democracy through games in Taiwanese schools

Taiwan’s secondary schools come top of global rankings in civic education, leaving Swiss schools in the dust. What makes Taiwan different?

Check out our selection of newsletters. Subscribe here.

The voices and shouts of Class 805 can already be heard in the corridor of Sanmin Junior High School. Through open doors, a room full of 14-year-old students can be seen tapping their tablets in concentration. Welcome to democracy class.

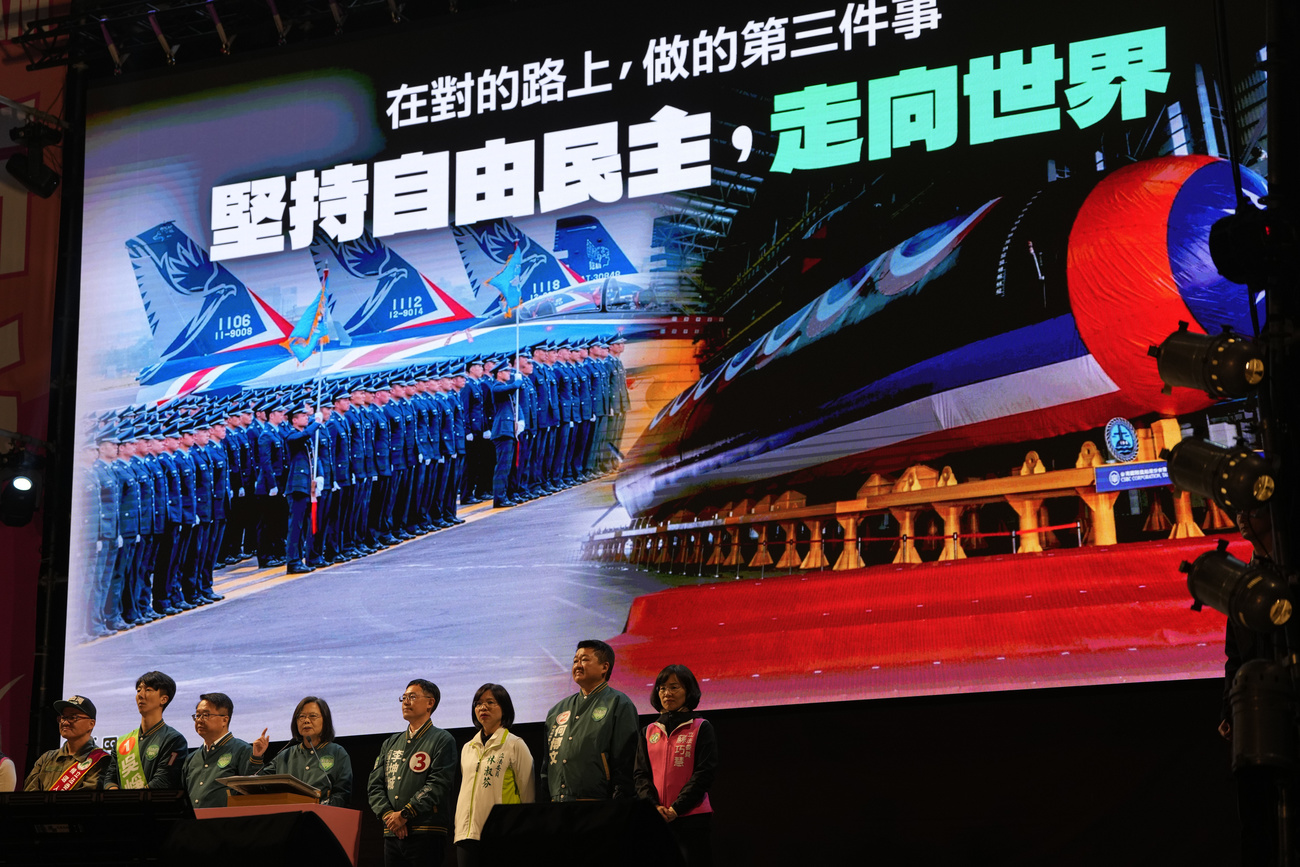

Their task is to identify the most important political players in national politics. In addition to faces and slogans, the teacher, Yi Ting Jhang, presents well-known symbols and pieces of music associated with different Taiwanese political camps on a screen at the front of the class.

“I know him,” a pupil, Jia-Ruei, shouts out to the class. “My parents are voting for him.” “No way,” says the pupil next to her, Yan-Cheng Hou. “I’d never vote for that guy.”

“After the politicians, now let’s take a look at the policies,” Jhang says, and presents the various parties’ policy proposals in a playful way using short, animated comic sequences.

The girls and boys in Class 805 first discuss these in small groups, and then as a class, before they are allowed to vote electronically and secretly for their political priorities for Taiwan.

This is a test run. Sanmin Junior High School, with 400 pupils, is one of several dozen pilot schools for the new curriculum, which is due to come into force in five years. Taiwan’s future curriculum aims to educate young people to become “global citizens”.

‘Democracy education’

“Democracy education” is already considered a core subject and has corresponding resources in terms of teaching materials and teacher training. “With the use of modern technologies such as generative artificial intelligence in the classroom, the new curriculum goes one step further,” Jhang explains.

She then presents the conclusion of the lively lesson to her students in the form of colourful tables on the screen: the politicians the class chose do not correspond to their political priorities.

“Don’t be fooled by politicians. Take a closer look,” the teacher says. The class responds in astonishment, and the objective of the day’s lesson has been achieved.

Taiwan invests more in democracy education than almost any other country in the world.

Special situation

The Swiss education expert Petra Huth sees this as a consequence of “the history of the introduction of democracy and the geopolitical environment”.

Attitudes in Switzerland are different, she says. “Many people here are convinced that we already live in the best democracy and that it’s enough if knowledge about it is taught at home, at the kitchen table.”

Around 24 million people live in Taiwan’s 36,000 square kilometres. For the island state, democracy education is seen as a survival strategy in the context of a hostile neighbourhood dominated by autocracy, she says. In Switzerland, with an area of 41,000 square kilometres and nine million inhabitants, surrounded by the peaceful European Union, political education is still treated as an unnecessary optional subject, Huth says.

The results are correspondingly different. “For the first time, our students achieved the best results worldwide,” says Mei-hui Liu, a professor at the National Taiwan Normal University, referring to the latest results of a large-scale comparative study.

The International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) directed by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) was implemented for the third cycle in 2022, with 24 participating countries worldwide. Young Taiwanese performed well on the “civic knowledge” measure. Switzerland took part only in the first study in 2009. Young people in Switzerland achieved rather average scores.

The global study of democracy education examines dozens of skills and competences that young people can use to become responsible and active citizens.

These include how young people view political participation, the value they place on state institutions and human rights, as well as how they view ethical issues as consumers.

Voting on the furniture

In Tainan, 350 kilometres south of the capital, Taipei, a visit to a high school is on the agenda. This afternoon, the four-member election committee is analysing the results of several student votes on furnishing and activities on the campus of Tainan First Senior High School.

This was preceded by collecting signatures in favour of certain proposals and debates in the school’s own parliament. “We are practising everything we will need later in life as adults,” says 18-year-old Shao-fan Wang, who chairs the election committee and can imagine going into politics as an adult.

But it seems Wang is somewhat alone in his desire for more political activity.

Not much political engagement outside school

“Most students say they don’t have the time or inclination for political engagement outside school,” says Mei-hui Liu. “We still have a lot of catching up to do when it comes to involving the younger generation in politics in Taiwan.”

The gap between the relatively well-prepared youth and the participation of young citizens in official politics is wider in Taiwan than in other democracies.

For example, a constitutional referendum that would have harmonised the voting and electoral age recently failed due to a lack of support. Today, young Taiwanese can sign popular initiatives and vote in referendums at the age of 18. But they are not allowed to vote in elections until they are 20. And anyone running for a local or national parliamentary seat must be at least 23.

Role model

Despite this contradiction, Huth, a political scientist and economist, sees Taiwan as a role model when it comes to anchoring democracy education in Swiss schools as an integral part of the curriculum.

“In Switzerland, lots of things have entered the national ‘Curriculum 21’,” she says, referring to the curriculum for 21 German-speaking cantons. “For example, cookery lessons. But civic education does not exist as a separate subject area – instead it’s an aspect of sustainable development and is integrated into learning objectives across all subjects.”

Huth, a former managing director of the Dialogue Foundation and a councillor in the municipality of Anwil in canton Basel Country, says that in Switzerland “national initiatives for democracy education are met with scepticism in the cantons, because education is the remit of the cantons”.

However, she sees it as “very important to start democracy education in schools at an early age, before children reach adolescence and have completely different concerns”.

More

Edited by Mark Livingston. Adapted from German by Catherine Hickley/ts

This article was amended slightly on 11 June 2024 to improve accuracy.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.