Sister republics: what the US and Switzerland have in common

Once upon a time, Switzerland and the United States were known as “sister republics”. Recently Donald Trump’s former ambassador to Switzerland evoked the idea again. In fact, the two states have shaped and influenced each other.

At the end of the American Civil War in April 1865, thousands of Swiss took part in celebrations of the Union’s victory. The feeling of solidarity was strong. Later that same month, some 20,000 Swiss signed condolences on the death of Abraham Lincoln.

This was a large number at a time when people’s understanding of themselves as citizens of a nation-state was relatively new – and signing petitions was not as convenient a procedure as it is today.

From northern Switzerland, authorities in canton Aargau addressed “our great sister republic beyond the ocean” in a feeling of deep fellowship.

More

Sister republics: Switzerland and the US

Today it may sound pretentious to draw comparisons between a world superpower with hundreds of millions of citizens and a region in tiny Switzerland. But the American side evoked brotherhood or sisterhood with this country. The government and people of Switzerland had never wavered “in their friendship to a larger sister republic”, US ambassador George Fogg wrote to the federal government in 1865.

There was a time when the two countries saw themselves as sister republics. Each developed its institutions with an eye on the other.

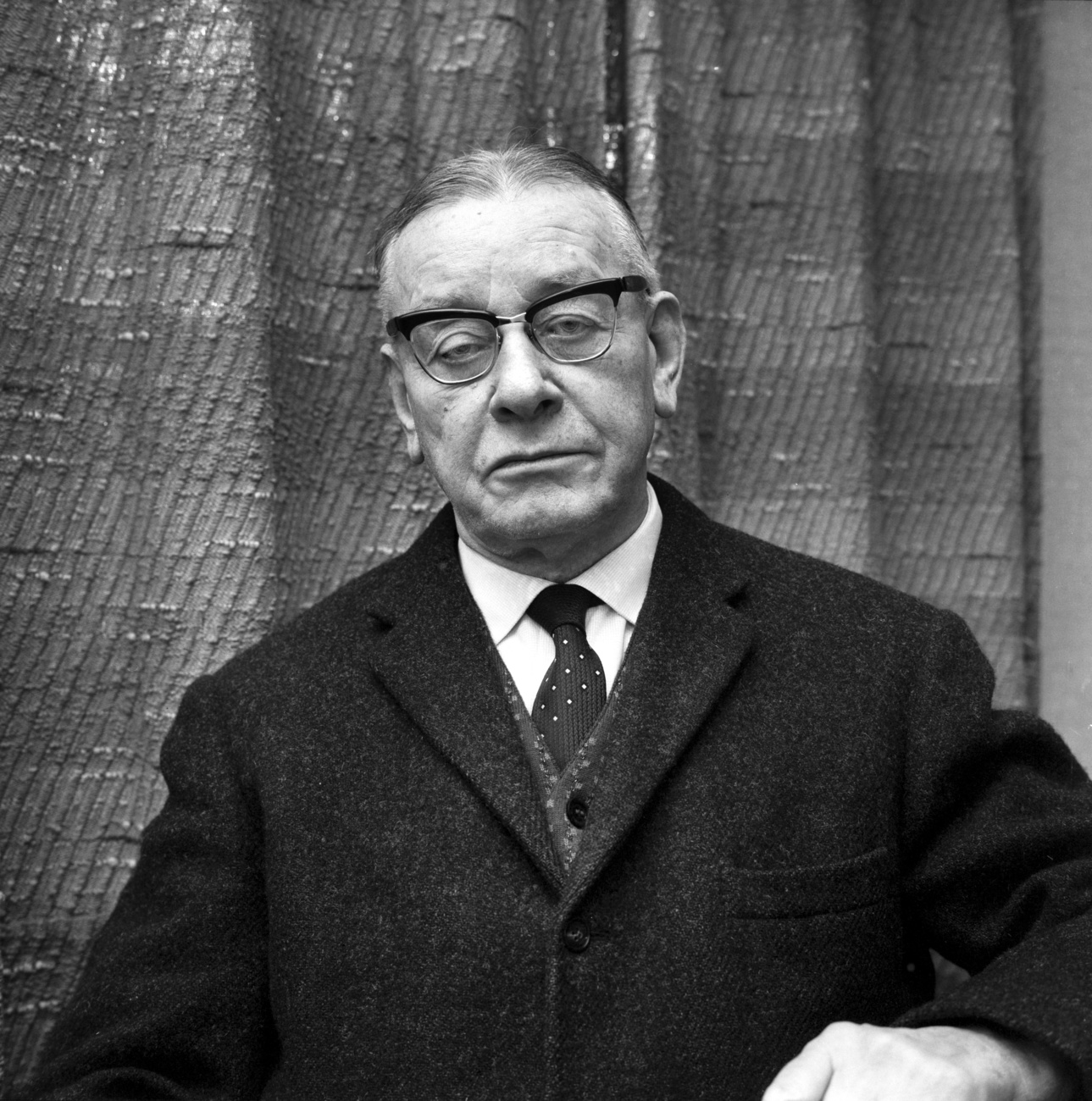

In the German version of his 1991 book, The Sister Republics, historian James H. Hutson wrote: “Beginning in 1776, political developments in the two countries often ran parallel, and at historic turning points, the constitution of one country served as a model to the other.”

A Swiss influence on the US Declaration of Independence

Even the most important statement in American history could be said to have a Swiss flavour, Hutson added.

More

How America shaped Geneva’s international role

In the 1770s, when Switzerland was still a loose confederation of states and the 13 colonies in the New World were asserting themselves against British rule, American founding fathers such as Thomas Jefferson were inspired by their reading of a Geneva philosopher named Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui.

Jean-Jacques who? Few would recognise the name today, even in Switzerland. Yet in the 18th century Burlamaqui enjoyed international popularity.

In the view of some writers like Harvard historian Morton G. White, reading Burlamaqui’s work had an impact on the introduction of the Declaration of Independence. His was the Swiss accent in the most important sentence in the document: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Scottish philosopher John Locke formulated these rights in a similar way but with a crucial difference in wording: Locke wrote of “life, liberty and property”. He mentioned “pursuing happiness” elsewhere.

Pursuit of happiness as a natural right

Burlamaqui was the first to identify the pursuit of happiness as a natural right from which just about everything is derived. He linked this right to the right to self-defence: when faced with an enemy, a person has the right to take up arms to defend their own safety and happiness.

This was an approach that the American founding fathers could readily understand during the War of Independence. And it’s one that still holds in the US: there is a direct line from the thinking of Burlamaqui (and his disciple Emer de Vattel) to that of Americans today who see the right to bear arms as a bedrock of their identity.

Not a loose confederation like pre-1848 Switzerland

As part of the constitutional process following the War of Independence, the founders of the American republic discussed the idea of a “Helvetic Confederation”. But in the end they rejected the concept. The Swiss cannot be said to form a unit, and have been at war with each other more than once, said Alexander Hamilton, the first finance minister of the US, in a key speech in 1787. Switzerland was a loose confederation of states – not a state, nor a republic.

It would take another half-century before Switzerland could be reborn as a unified state, a true sister republic. Supporters of a republican Switzerland looked to the US as a point of reference until the brief civil war of 1847 between the cantons. Philosopher Ignaz Paul Troxler published a text on New Year’s Day 1848 called The constitution of the United States of North America as a model for Swiss federal reform. This made Troxler the “intellectual midwife of the Swiss federal state”, to quote the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

Federalism and the bicameral system

The two houses of parliament in Bern are in fact copied from the House of Representatives and Senate in Washington. Beyond the bicameral system, which allow even cantons with a small population to be heard, Switzerland stands for a combination of centralised state and cantons. The cantons can decide for themselves in many matters. The US constitution was a model for the Alpine country’s fundamental rights and human rights and for the separation of powers.

More

Why people in Switzerland trust the state

But in many respects, there were differences between the two even back in 1848. In Switzerland, parliament elects judges to the Federal Court. Unlike the US Supreme Court, the Swiss court is not a constitutional court. At the executive level, the Swiss federal cabinet of seven ministers is a completely different concept from the American presidential system.

High point of closeness was the Civil War

The two “sister republics” reached the high point of political and ideological fellowship at the end of the American Civil War in the 1860s. During the war, John Watts de Peyster gave a moving address to the Vermont State Historical Society. Watts de Peyster compared the brief Swiss civil conflict of 1847 (the Sonderbund war) to the war between the American states.

Both conflicts were a fight against reactionary forces that opposed “the tide of liberal progress and freedom”. Just as the 1847 war made the Swiss more determined to succeed as a republic, the Union victory over the Confederates would bring a form of government that was more in keeping with American destiny. The Swiss federal state embodied the spirit of freedom in Europe, Watts de Peyster declared. It alone was worthy of comparison with the US, he added: “Republics must learn from republics!”

‘Eternal bond of faith and friendship’

Switzerland at the time was surrounded by monarchies. The Swiss federal government, the liberal cantons and many Swiss felt a great bond with the Unionists in America, expressed for example in the 20,000 signatures mourning Lincoln’s death.

In 1865 the newspaper Aargauer Nachrichten wrote about the US after the Civil War, which it called a decisive moment: “Should Switzerland not rise and shake hands with its friend?” The sister republic, the paper added, would “take little Switzerland’s hand with love”. This would be the beginning of an “eternal, close bond of friendship and mutual loyalty”.

Things turned out somewhat differently – both in diplomacy and institutionally. When Switzerland brought in proportional representation in 1919, it changed the political makeup of parliament. The more parties there were with a seat in the Swiss government, the more the country followed a policy of compromise and balance. In the US, by contrast, Democrat and Republican presidents run to overturn everything their predecessor has done. Already in the 19th century the US was far from neutral, though it had a policy of non-interference when it came to Europe. This led to a certain bond with Switzerland, a neutral country since 1815, which lasted until America entered the First World War. Things changed given the important geopolitical role the US has played since then, especially during the Cold War.

More

What does the future hold for Swiss neutrality?

Switzerland gets a birthday present

Today the notion of “sister republics” is rarely mentioned. But it still has some currency in the year 2024. Trump’s former ambassador to Switzerland, Ed McMullen, used it to describe the two countries’ relationship in an interview with the newspaper Sonntagszeitung. He declared that defeated president and now candidate Donald Trump understood and admired “the history of the Swiss Confederation – it is our ‘sister republic’.”

More than 30 years ago, Hutson outlined the common past of the “sister republics” in considerable detail. His work was a birthday gift from the US to Switzerland – 700 years after the mythic Rütli Oath, celebrated in 1991.

A few years later, the scandal surrounding dormant assets of Holocaust victims and Switzerland’s dubious financial practices during the Second World War damaged this country’s reputation in the US. It was inconceivable that the US would give another birthday present to its sister republic after that.

More

Switzerland is still grappling with dark chapters of its history

The dormant assets scandal is symptomatic of the way the two countries have drifted apart. While the American republic has become a world power and does not hesitate to intervene in pursuit of its values and interests, little Switzerland still emphasises its neutrality – and interprets it in ways that the rest of the world struggles to understand.

Edited by David Eugster. Adapted from German by Terence MacNamee/gw

Locke’s influence on the American Declaration of Independence is generally accepted – but it is also known that the authors of the document had examined other sources too. Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui was a well-known author in the 18th century who popularised Lockean ideas among a wide readership. Burlamaqui further developed the idea of natural right. Whereas the idea of the “pursuit of happiness” already occurs in Locke’s writings, Burlamaqui made happiness the central focus. He thought of it as a natural right.

Morton G. White was the first modern historian to explicitly document Burlamaqui’s influence on the Declaration of Independence. White based his thesis about Burlamaqui in particular on Thomas Jefferson’s original draft of the document.

The quotes from historical sources are taken from George Müller’s 1944 dissertation on Swiss public opinion about the American civil war (Der amerikanische Sezessionskrieg in der Schweizerischen öffentlichen Meinung) and from The Sister Republics by James H. Hutson, 1991.

Do you want to read our weekly top stories? Subscribe here.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.