‘Democracy is an unfinished work of art’

Andreas Gross, a leading Swiss political scientist, talks to swissinfo.ch about the state of democracy in the small Alpine nation, and draws comparisons with Taiwan, which recently introduced direct democracy into its political process.

swissinfo.ch met Gross in the small mediaeval town of Saint-Ursanne in western Switzerland, together with Hedy Chiu, a visiting journalist from Taiwan. This is an abridged version of the interview.

swissinfo.ch: You once referred to yourself as a “craftsman of democracy.” Is democracy really something that can be crafted?

Andreas Gross: I said that I am a craftsman of democracy, not because democracy is something that can be manufactured, but to say that democracy is a fragile political art that is complex in structure and that is always in motion.

It relies on least 150 components, such as the free exchange of information and public debate. The quality of each component and the synergy between the components determine the quality of this piece of art. But one important component of the mosaic of democracy is the direct democratic polity which really has to be well designed; and this design is also crucial for the quality of direct democracy.

Andreas Gross is former lawmaker, leading expert on direct democracy, author and researcher.

Born in 1952, he spent the first seven years of his life in Japan before his family moved to Switzerland. He studied political science and worked as a researcher, lecturer and politician at a local, national and international level.

He was a member of the Swiss parliament from 1991 to 2015 and a Swiss representative of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe.

He headed the Social Democratic group in the Council for six years. Gross was one of the leading lights of an initiative to abolish the Swiss army, rejected by voters in 1989, and a co-founder of the initiative for Switzerland to join the UN, approved in 2002. He also acted as international observer of more than 90 elections in Europe.

swissinfo.ch: What do you think of the state of democracy in Switzerland?

A.G.: Democracy will never be perfect, it only has a relative, more or less complete state. The degree of completion of the Swiss democratic system is very high. For example, citizens have a good chance to fulfil their political rights. They also have the opportunity to substantially influence political decisions through referendums.

swissinfo.ch: Where does Switzerland still need to improve its political system?

A.G.: There are three major weaknesses in the Swiss democracy. First of all, Switzerland is the only country in Europe with no regulations on party financing, which leads to opaque sources of funding for Swiss political parties.

Secondly, the definition of democracy is that all people have the right to participate in decisions that affect them. But in Switzerland, one in four residents do not have the right to participate in voting related to their interests, because in most cases, only those with Swiss nationality can vote. Becoming a citizen is a very lengthy process.

Thirdly, the interface between human rights and direct democracy is not well done in the Swiss constitution. We have to protect the fundamental rights better against the will of the majority. Otherwise we discredit direct democracy.

swissinfo.ch: The goal of democracy might well be to satisfy citizens’ demands, but on certain issues, there’s almost an even balance between those who support and those who oppose certain issues. The fact that one party wins with a slight advantage means that a large proportion of the electorate group on the other side will be disappointed, exacerbating the polarisation of societies.

If we look, for example, at the conflict in the Swiss city of Moutier, which has for decades tried to move from canton Bern to canton Jura. Isn’t it hard to solve these issues by majority rule?

A.G.: If the number of supporters and opponents is near equal and there is no sign of compromise on both sides or, objectively, as in the case of Moutier, there is no possibility of a compromise or a middle way, then there is undoubtedly a problem.

However, in this specific case, over the past 30 years most voters expressed the view in communal elections that they wanted to merge into the state of Jura. The nature of some referendums that pit two opposing sides against each other can be too primitive and hurtful.

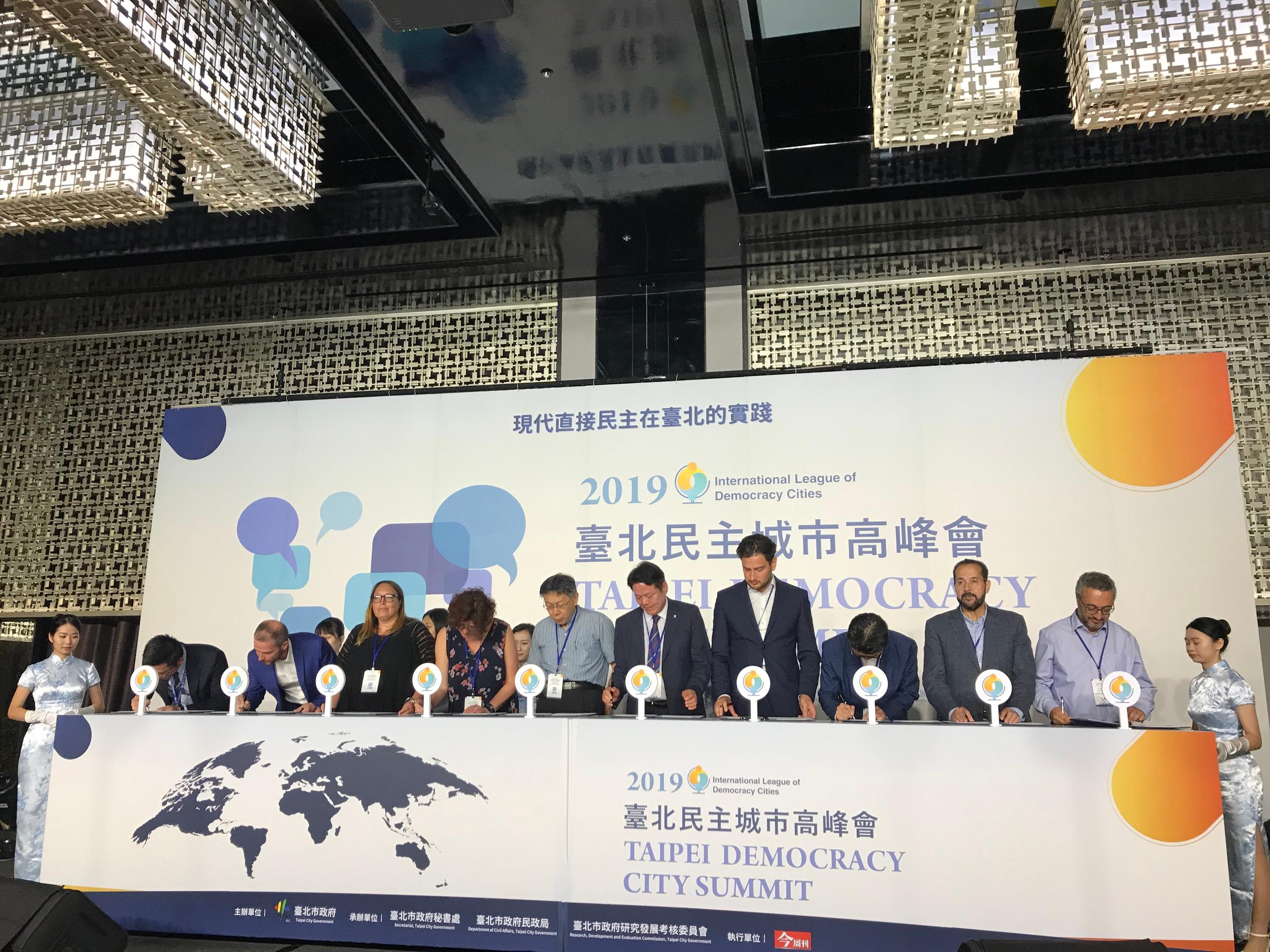

This autumn, swissinfo.ch puts a spotlight on Taiwan.

Two journalists from the island joined us in Switzerland to jointly report on various issues.

Our reporters also participated at the World Forum for Democracy 2019, which took place October 2-5 in Taichung and Taipei, and profiled Swiss citizens living in Taiwan. The next global forum will take place in the Swiss capital, Bern, next year.

Majority rule is a relatively primitive element of democracy. As long as the principle of equality of political rights of “one person, one vote” is respected, I don’t see an alternative to respecting the will of 51% of voters. If we’d set the threshold for majority decisions at 60%, that would mean that we consider the vote of each member of the 60%-majority to be worth less than those of the members of the 40%-minority group.

One alternative could be a ten-point score-voting system. Voters can distribute, say, three of ten points in a referendum bill, if they approve only 30% of the motion, and so on. If a referendum receives a 51% score in the overall score, then it will pass. Such a change would require a lot of training and public education.

swissinfo.ch: If we look at Taiwan, voters appeared to stick to party lines in the first round of referendums last year, whereas in Switzerland the views of voters in referendums are less tied to their party allegiance. Why?

A.G.: It takes time for a society to embrace direct democracy as something that not being steered by party politics. Taiwan is three times bigger than Switzerland and its democracy more than 100 years younger, so you need much more time. The 55% participation rate is a good start. There’s much to be improved, but as the process improves, the chance of a higher participation rate increases.

In Taiwan, political parties precede the introduction of direct democracy, but in Switzerland it’s the other way around. The public’s identification with political parties here is generally weaker. The Swiss also traditionally consider referenda as opportunities to make personal choices that can go against their party loyalties.

This learning process of overcoming and eventually shaping party policies is one of the crucial outcomes of implementing a system of direct democracy.

swissinfo.ch: Last year, Taiwan’s first round of referendums was criticized by some as mere large-scale polls that cost a fortune, but don’t change anything. What do you make of such a situation?

A.G.: The result of a referendum must have legal guarantees to be truly meaningful and give legitimacy to the process. A purely consultative vote is nothing more than a political game and a momentary depiction of the public opinion, not a product of deliberation and interaction. A real referendum should be treated as seriously as a matter of life and death, because it might be as important as that.

This article was part of a cooperation between at Commonwealth MagazineExternal link and swissinfo.ch.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.