The Swiss constitution – a mix of democracy and federalism

The first version of the Swiss constitution was a breakthrough on the road to democratisation. It gave the cantons more autonomy and paved the way for creating one of the greatest democracies in Europe. However, it was far from perfect. It triggered numerous crises and failed to put an end to injustice.

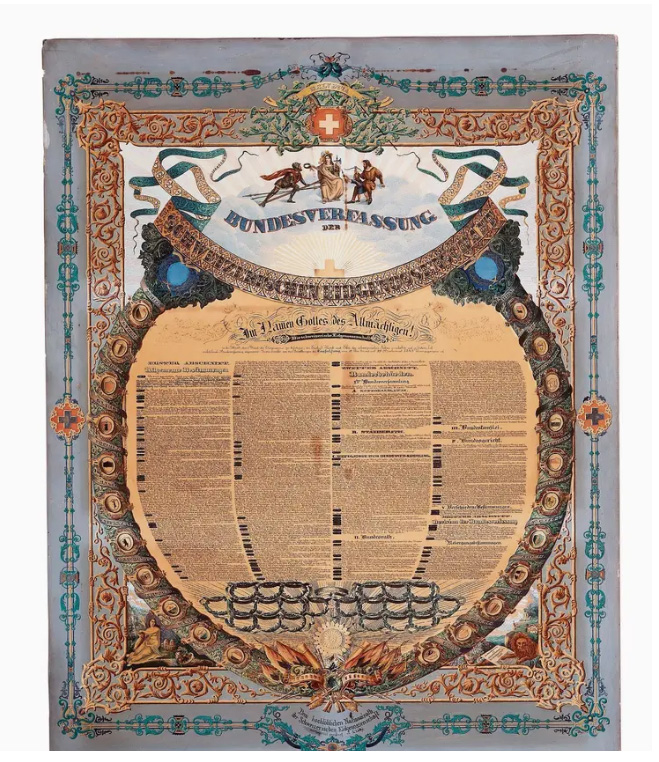

On September 12, 1848, the Federal Diet, a legislative assembly bringing together the Swiss cantons, adopted the first federal constitution. The cantons’ representatives drafted it in less than 50 days during their regular meetings at a Bern restaurant which is now known as Zum Aeusseren Stand. These were the first steps towards a modern state.

The first parliamentary elections to select the cantons’ representatives for the two chambers – the House of Representatives and the Senate – were called only two days after the constitution was adopted. The House of Representatives and the Senate worked quickly to elect the members of the Federal Council, which in turn formed the national government. The speed of these endeavors sent a clear message to the world: a new democracy was born.

This series in several parts is tailored for our author: Claude Longchamp’s expertise makes him the man who can bring alive the places where important things happened.

Longchamp was a founder of the research institute gfs.bern and is the most experienced political analyst in Switzerland. He is also a historian. Combining these disciplines, Longchamp has for many years given highly acclaimed historic tours of Bern and other sites.

“Longchamp performs democracy,” was one journalist’s headline on a report about a city tour.

This multimedia series, which the author is producing exclusively for SWI swissinfo.ch, doesn’t concentrate on cities – instead its focus is on important places.

He also posts regular contributions on FacebookExternal link, InstagramExternal link and TwitterExternal link.

This was the third attempt to establish a modern democracy. The first attempt was triggered by the French invasion of Switzerland in 1798, but it failed dismally after five years. The second attempt came in 1830-31, when the autonomous cantons wanted to introduce a new federal constitution. It was met with huge resistance by the Conservatives and Radicals and never got off the ground.

“The third attempt succeeded by striking the right balance between principles of pure democracy and federalism.”

The third attempt succeeded by striking the right balance between principles of pure democracy and federalism. It created the largest possible domestic market for the emerging industrial economies and had the support of Britain on a political and diplomatic level. None of this would have happened had Switzerland not gone through a civil war ten months prior to the founding of the state.

Risky business

While Switzerland succeeded in establishing a democracy, neighbouring countries tried and failed to do so. Bourgeois revolutions took place in Paris, Munich, Berlin, Vienna, Palermo and Venice, but they did not manage to establish a lasting democratic state. Their monarchs always regained power.

The leap into a modern democratic world carried some risks for Switzerland. The Alpine nation could not quit the federal treaty which was adopted by the Congress of Vienna in March 1815 on its own. It was in place and that was that.

More

The day Switzerland became neutral

After the Liberals and Radicals reunited to become the Radical-Liberal party, they emerged as the biggest winner of the 1848 parliamentary elections achieving a 70% majority in the federal assembly. This gave them the freedom to allocate the seats of the Federal Council to their liking.

The cantons of Bern, Zurich and Vaud were each allocated a permanent seat while the remaining four seats were divided between the other cantons. The French and Italian speaking minorities received one representative each, the Catholics got two.

On November 16, 1848, seven members of the Radical-Liberal party were elected to the Federal Council which was clear sign for the new beginning. The seven ministers represented the different political perspectives of the moderate Liberals and the assertive Radicals which gave them sufficient sovereignty enough to abrogate the old federal treaty. At the end of 1848, Bern became the seat of the government making it a federal city, but not the capital.

American idol

Even though Switzerland’s government structure was based on the US model, the composition of parliament and the election of the Federal Council were two major bones of contention in the democratisation process.

In the end, it was decided that parliament should be composed of two chambers with equal powers; the cantons should retain their sovereignty unless national matters were concerned; and, mirroring the US, the seven members of the Federal Council should not be elected by the people but by parliament.

The governing Radical-Liberals agreed that all elected ministers had to step down at the end of their three-year term and run for the House of Representatives if they wanted to be re-elected into the government.

Even though it was not laid down in the constitution, this two-tier system survived until the 1890s when it was finally abolished as it did not concur with the separation of powers.

The adoption of the new constitution turned out to be tricky as the Swiss did not vote on a national but on a cantonal level. In the end, 15 ½ cantons voted in favour of the new constitution and 6 and a half rejected it, which was sufficient for the Federal Diet to adopt it.

The cantons that voted against the constitution had to decide whether they wanted to accept the overall ruling, which was their democratic right, or not. But in the end, they were all forced to adopt it. This was a turning point for modern Swiss politics.

A few limitations

Switzerland’s democracy was far from perfect. Women were not allowed to vote and the male-dominated society, which was strengthened by the civil war, did not even think about entertaining women’s suffrage. Nationwide voting was only introduced in 1874; there was no permanent federal court; and criminal law was under the jurisdiction of the Federal Council.

Switzerland has a hybrid system of government unlike other nations that either use a parliamentary or a presidential system.

Even though the government is not directly elected by the people, there is no provision for a parliamentary no-confidence motion for an individual minister or for the dissolution of parliament before it has finished its four-year-term.

Parliament has declined to re-elect a sitting cabinet minister only four times in Swiss history. The first was in 1854 when the Radical Party’s Ulrich Ochsenbein was voted out of office, and the last time was in 2007 when Christoph Blocher was ousted in his bid for re-election.

This is typical for directorial systems which allow parliament to elect a government but not to oust it. Collective governments like Switzerland, South Africa or Botswana use such directorial systems which was instituted in France in 1795, but has since been abolished.

The Swiss constitution stated that Switzerland was a Christian state which was a serious mistake as it soon led to a constitutional crisis. It was not inclusive of its Jewish population.

France, the US and the Netherlands threatened to impose economic sanctions on Switzerland unless the non-Swiss Jewish were given the same rights as Swiss Christians. This required an amendment of the constitution which had not been envisaged. Hence in 1866, the first small constitutional reform was carried out with referendums on nine individual articles. Members of the Jewish community were eventually granted freedom of domicile, but only obtained the freedom to practise their religion in 1874.

Ueli Ochsenbein – the forgotten founding father

Ueli Ochsenbein, military leader and head of the Radicals of Bern, was a tragic figure during the formation of the young federal state. After serving his two terms as minister, the actual founding father of the 1848 constitution was voted out of office. The ruling Radicals turned their backs on him because he had supported the Radicals, Liberals and Conservatives in forming a political party in canton Bern.

After being dismissed from his post as military leader, Ochsenbein joined the French army where he was promoted to the rank of general. Joining a foreign army would be inconceivable in modern times, however, it was only prohibited in Switzerland in 1874.

Ochsenbein, who sunk into oblivion in Swiss history, has recently been rehabilitated thanks to a comprehensive biography. He is due to regain his place in history during the official celebrations of the 175th anniversary of the federal constitution in 2023.

Translated by Billi Bierling, edited by Dominique Soguel

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=cb688ed5)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.