Trump, Biden and hatred: how US polarisation affects Americans in Switzerland

Two parties and two presidential candidates – both of whom are unpopular with many voters. Few societies are as polarised as the United States. We gathered impressions from a Democrat, a Republican and an independent, all living in Switzerland, the land of compromise.

“Someone recently wrote on Facebook that Joe Biden is like Hitler,” says Sue Rickenbacher, an American. The two main candidates for the presidency – the current president, Joe Biden, and the former president, Donald Trump – are unpopularExternal link with large sections of the US population. Rickenbacher is no Biden fanExternal link, but how can she respond to this kind of comparison? “When someone writes something like that, it’s difficult to stand in the middle,” she says.

On July 21, Joe Biden withdrew as the Democratic presidential candidate. Has emotional polarisation changed now that Kamala Harris and Donald Trump are running against each other?

Not for Republican Tariq Dennison. He has the impression that in the race between Harris and Trump, “perhaps 60 to 80% of Americans” are wondering whether these are really the best candidates in a population of around 340 million.

In speaking to those who want to vote for Harris, Dennison gets the impression that most would rather vote against Trump than for Harris. He has yet to meet anyone who proudly supports Harris because of her political programme and leadership qualities. “I find that a little disturbing,” says Dennison.

For Sue Rickenbacher, something has really changed: “I feel the emotional polarisation is completely different than with the Trump vs. Biden combo.” The “two men” portrayed each other “as a threat to the world.” Kamala Harris is sticking to a “positive, forward-looking message.” Trump, on the other hand, seems like “a bully, not a statesman.” In “a perfect world,” Harris would not be her choice. But Rickenbacher will vote for her.

Democrat Liz Voss attended the Democratic Party convention in Chicago. The atmosphere was electric. She also believes that the emotional polarisation is “a little less now.” The reason: “Voters are happy that there is a change compared to 2020.”

Biden and Trump have already faced each other once in the 2020 presidential election.

After the assassination attempt on Trump on July 13, Rickenbacher believes the election campaign has been decided. “One person was killed. Trump is now a victim and seems stronger at the same time. Biden will have even more problems getting his message across.”

More

Trump shooting: Swiss president condemns ‘unacceptable’ attack

The attack shocked Rickenbacher. “But on the other hand, if you think about Trump’s violent rhetoric or the storming of the Capitol on January 6, 2021, it’s not surprising. The wrong person hears this and feels justified in carrying out an attack.”

Sue Rickenbacher has voted for George W. Bush and Barack Obama

She doesn’t speak like a conservative but doesn’t agree with all the Democrats’ policies. She would like to vote for a moderate Republican: Chris Christie, Nikki Haley or John Kasich would all have got her vote if they had been running.

Instead, the candidates in the race are “very polarising” in Rickenbacher’s view. She wants to be in the centre. The retired marketing manager is a proud independent voter.

The tense atmosphere penetrates her private life. “I can no longer have a conversation about politics with my brother-in-law. He thinks the last election was stolen,” she says. Rickenbacher already lost a friend over Obama’s election.

She rarely gets involved in arguments on the internet. Almost all the Americans she sees regularly are not Trump supporters, because most Americans in Switzerland are liberal. Rickenbacher is convinced that this is due to the broader perspective you gain when you live abroad. In Switzerland, for example, you learn to appreciate the public healthcare system, she says.

She has lived in Switzerland since the 1990s. Of the three Americans with whom SWI swissinfo.ch spoke about emotional polarisation, she has lived outside the US for the longest.

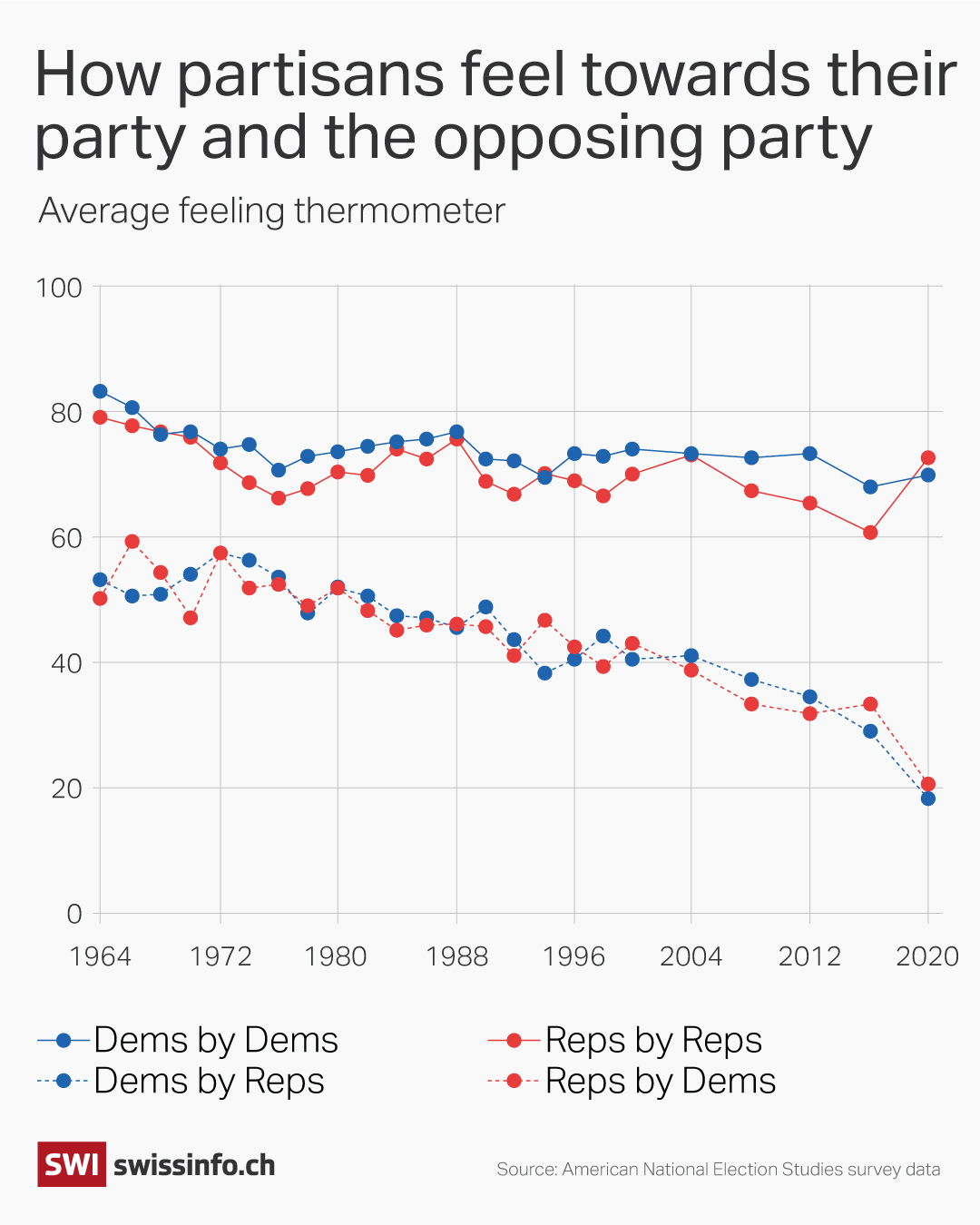

When polarisation means not only a divergence on factual issues but also describes an emotional rift between groups, it is referred to as affective or emotional polarisation. As an example, this would mean a Republican thinking that anyone who is a Democrat is a bad person and vice versa.

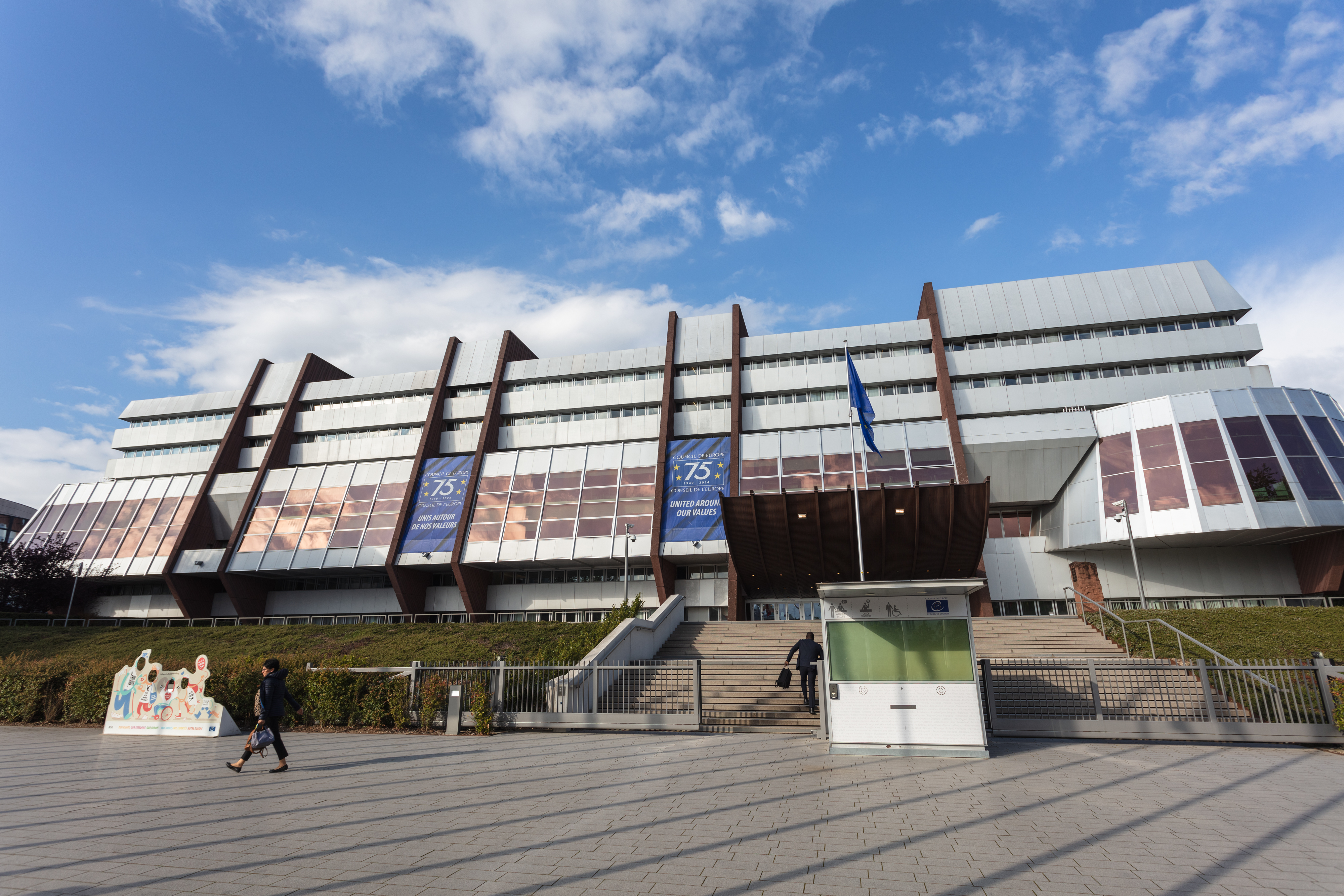

The political economists Alois Stutzer and Benjamin Jansen have researched affective polarisation in Switzerland on the basis of a Swiss Broadcasting Corporation survey. They found that affective polarisation in Switzerland has not increased over the past 20 years.

The findings were contrary to Stutzer’s expectations. “I was surprised by our results,” he says. “I had imagined that the change in political style would leave its mark.” He had made the original assumption because of “political campaigns that aimed to open up or at least nurture rifts”.

More

‘Security here, freedom there’ – insights from a US trucker festival in Switzerland

Liz Voss is campaigning for the Democrats

Liz Voss says she has received leaflets from the right-wing Swiss People’s Party that made her feel unwelcome in Switzerland. But she feels at home in Allschwil, near Basel. Voss is a staunch Democrat and is involved with Democrats Abroad. Although Biden is not her favourite candidate either, she has a big project this year: mobilising for his re-election. She wants to ensure that as many Democrats and moderates as possible go out to vote. She wants to maintain this focus even after the attack on Trump. Instead of becoming part of the “deepening rift”, she is talking about stricter gun laws.

Speaking to Voss, it becomes clear she is a committed campaigner. A “certain degree of emotional polarisation” can certainly stimulate democracy, explains Jansen, a political economist. Those who are “emotionally polarised” are more likely to vote or become politically active, he says.

According to his colleague Alois Stutzer, affective polarisation becomes “critical” “when emotionally polarised citizens re-elect politicians from ‘their’ party even when they misbehave”.

But unlike in Switzerland, affective polarisation has grown considerably in the US. “In the US, ‘us versus them’ is easy,” Stutzer says. This, he believes, is down to the two-party system, because without an outside third party, “political communication that belittles the other side becomes an attractive strategy”.

According to Stutzer’s observations, “identification with one’s own party and the demarcation from supporters of the other party” increasingly characterises “everyday private life”. While a son-in-law with a different religion, for example, is less of a problem today, “a different party affiliation is a much bigger problem”.

Voss says she is happy that she almost only has dealings with American Democrats. At the same time, she appreciates that she has more chance encounters in her everyday life in Switzerland. In the US, she moved “from the front door to the car, from the car to the office” and hardly met anyone outside the workplace. But the only way to convince people who think differently is through personal dialogue, she says. For that reason, she is concerned that many debates have shifted to the internet.

She sees just how difficult nuanced communication is on the internet when talking to family members who think differently politically. She avoids confrontation across the Atlantic. “It’s better not to fight out conflicts at a distance because there are certain levels of communication that are missing, such as body language,” she says.

More

Five events that shaped contemporary Swiss-American relations

One issue that concerns Voss deeply is access to abortion. She refers to surveys showing that a clear majority of Americans are in favour of legal abortions. She sees the banning of abortions in some US states as unlawful. “I’m not just going to stand by and watch my niece’s rights being taken away. My daughter lives here, but she also only has a US passport.”

Voss sees Switzerland as a country of political diversity. “I admire the political landscape and the fact that there are so many different parties,” she says. Despite her own political stance, she would like to see a third, moderate party in the US. “The two parties lean so far to the left or right that there’s no longer any common denominator,” she says. Voss is therefore hoping for a centrist party that could facilitate compromises and soften discussions in the heated climate.

The park in Allschwil is empty, which is why Voss laughs when asked whether it’s quieter in Switzerland. Yes, it is, she says. But at the same time, she doesn’t meet any Americans who think completely differently. Voss doesn’t know any Republicans in Switzerland. Probably because there aren’t many.

Tariq Dennison is one. Dennison sits with a bottle of Rivella in his neighbour’s organic restaurant in Weinfelden, a small town in Thurgau. Family, faith, the idea of “American exceptionalism” and building his own business have shaped his path to becoming a “classic American conservative”, he says.

He talks about growing up on US military bases in Cold War West Germany, his first political memory – the 1984 election campaign, which Ronald Reagan won hands down – and his enthusiasm for debating, which he pursued in high school.

This becomes clear in conversation. No matter what the topic, Dennison, an economist, first lists the pros and cons before coming to his conclusion. Even on the highly charged topic of abortion. He is in favour of “solutions that are rational and pragmatic”. On the one hand, he “strongly believes in the value of life”, but on the other hand he is also open to “the many reasons why voters do not agree with a pro-life position”.

Dennison believes abortions in the eighth month “can indisputably be considered murder” – except for “difficult cases” in which the mother’s life is in danger. “It is one of the duties of a moral government to protect life from such suffering.” With regard to “all less extreme cases and shades of grey”, however, Dennison would like to see a “return to rational discussions”. He believes that in the end, everyone would agree that a world with fewer abortions would be a better one.

As nuanced as Dennison is in his judgement, he expects other qualities from a US president. He criticises Obama for “leading from behind”. Obama was too concerned with what the European Union in Brussels thought of him, he says. In contrast, he praises Trump for being “unapologetically America First”. He doesn’t care what other governments want from him, Dennison says.

Dennison does not consider himself a Trump fan, but he voted for him in 2016 and 2020 and says he plans to vote for him again in 2024, “especially after watching his debate on June 27 against the current president, Joe Biden”.

At the same time, Dennison considers it “very unfortunate that the polarisation in the US has gotten worse in the last ten years since Donald Trump appeared on the political scene”.

Dennison looks back into American history several times during the interview. When asked whether a third party or a new electoral system would resolve the tense mood in the US, he points to “what happened in the multi-party elections of 1824, 1912 and 1992”. These are examples of “how third parties can be counterproductive in the current US electoral system”, he says.

He describes the ideas of the American founding fathers as “strong pillars” of his political position: life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness and the rights and duties of an individual to defend his family, freedom and property.

More

Sister republics: what the US and Switzerland have in common

“In general, the USA has solid institutions,” says Dennison. A system that has survived a civil war and two world wars “among many other challenges” does not need major reforms, he says. The US Congress, Senate and judiciary control the president and can “balance the priorities of Americans better than the alternatives”.

When asked about the storming of the Capitol on January 6, 2021, Dennison describes those involved “as a mob, whom many Trump voters also condemn”. He himself is very clear on this: “Our country should be above an armed uprising after the victory of a political opponent.”

But his attitude towards what happened after the last US elections makes Dennison part of a minority among Republican supporters in the US: 60% of Republican votersExternal link believe the 2020 election was “stolen”.

In the 2024 election campaign, TrumpExternal link is also repeating the claim that he won the election four years ago.

“Any system can fail,” Rickenbacher says. Voss fears that Trump will not accept his defeat again and that a similar situation to 2021 could then arise. For Dennison, those who stormed the Capitol in the name of Donald Trump are a mob.

All three regret the extent of the polarisation. All three recognise the shift of debates to social media as part of the problem – and Trump’s appearance on the political stage as the moment when the situation came to a head. There is a surprising amount of agreement.

Political economist Benjamin Jansen from the University of Basel describes “affective party polarisation” as the extent to which “people sympathise more with their own party than other political parties and their respective members”. Those who have no sympathy or antipathy towards people because of their party affiliation “are therefore not considered emotionally polarised and vice versa”.

According to Jansen, there can also be strong emotional polarisation between groups even if the differences in substance are not that great. Diverse opinions in themselves are positive for a democracy, which is why Jansen believes it is important to differentiate between substantive and affective polarisation: The latter “makes exchanges between groups more difficult. Discrepancies in content are not in themselves a problem for a democracy; on the contrary, they make such a system productive in the first place.”

But the reason why one can imagine Rickenbacher, Dennison and Voss in an engaged but respectful discussion is probably because all three condemn what happened after the last US election. In doing so, they recognise the same reality.

If the three of them were to meet, the discussion would probably be no more emotional than is good for the democratic debate.

Edited by Mark Livingston. Translated from German by Catherine Hickley/ts

This article was updated on 05.09.2024 to incorporate viewpoints after Kamala Harris was declared the Democratic candidate.

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.