South Korea’s Democracy at the Crossroads

A year after one of the most successful democratic revolutions in modern history, South Korea has come a long way in a short time. But the months to come will require new feats of leadership and people power.

On the ground in the small village of Panmunjeom, time seems to stand still. Here, grim-looking soldiers from North and South Korea face each other across a span of a few metres.

As a foreign visitor to this so-called Joint Security Area, I had to sign a military document accepting possible “injury or death as a direct result of enemy action”. South Korean citizens are not allowed to visit this place.

Just a little over a year ago, this scene was fully backed up by the unforgiving rhetoric and politics out of both Seoul and Pyongyang.

Hate rants by Northern dictator Kim Jong-un against the “American dogs in the South” were duly countered by then-South Korean President Park Geun-Hye who called the North Koreans “coward Communists”.

Many thought that the two Koreas and the world were heading towards the first nuclear war since 1945. This feeling was reinforced by clumsy actions from countries like China, Russia, the United States and Japan, all tied up in the conflict. South Korea seemed to have become a very, very distant destination for anyone reporting on and supporting democracy.

That was just 400 days ago.

Today, South Korea has become a global beacon of innovation and hopes for peace and democratic progress. What happened?

On March 10, 2017, the first popularly elected female head of state, Park Geun-Hye, was deposed by South Korea’s Constitutional Court via unanimous decision.

Millions of brave citizens, young and old, had protested against their corrupt and undemocratic leader, the daughter of South Korea’s latest military dictator Park Chung-hee. They celebrated on the streets and squares of Seoul and many other cities across South Korea after her impeachment.

Thirty years after the country’s 1987 revolution – the so-called June 10 uprising which eventually ended the military dictatorship – a new generation of South Koreans successfully launched a new one, called the “Candlelight Revolution”.

Their demand was not just an end to bad governmental practices, but the introduction of modern direct democracy in this country of more than 51 million people.

As a consequence, pro-democracy activist Moon Jae-in was elected as South Korea’s new president on May 9 of last year. In his inaugural speech, Moon Jae-in promised to honour the “Candlelight” revolution by promoting direct democracy during his tenure.

Reporting from South KoreaExternal link during those days, I met an old lady in a park outside the presidential palace who said: “This is the happiest day of my life, now we have the possibility to get a truly democratic and peaceful society.”

A new direct democratic constitution

When I returned to South Korea for my direct democracy world tour (#ddworldtour), I experienced new and powerful expressions of what has become a global movement, triggered by the South Korean democracy wave. It is an impressive counterpoint to the widespread talk about democratic regress in other parts of the world.

In Seoul, I witnessed on March 26 the delivery of a new constitutional draft by President Moon to the National Assembly (done electronically from Dubai, where he was on an overseas trip). The submitted proposals include a nationwide citizens’ initiative, as well as a recall option for all elected offices plus a limitation on the currently far-reaching powers of the head of state.

“Now we are trying to quickly move from a dark past into a very bright future,” said Professor Lee Jung-Ok, who chaired an assessment session around the new constitution in the National Assembly.

South Korea’s current constitution, dating back to the 1987 democratic revolution, simply deleted the most obvious aberrations of the previous military regimes but gave all relevant powers to one office, the presidency.

It proved to be a truly unhealthy solution since all three officeholders preceding the current president have been jailed. Last week, former South Korean President Lee Myung-bak (who served from 2008 to 2013) was arrested, accused of widespread corruption.

Most Koreans are welcoming the end of back-door politics that have been dominated by powerful conglomerates like Samsung, Hyundai or LG – the so-called “chaebols” – for decades. In spite of much economic progress, the unhealthy influence of those big players has held South Korea back in many ways, including addressing many social issues like gender equality or workplace rights.

Navigating a powerful shift

But now, everything seems to have shifted towards a path which often surprises the restless Koreans themselves.

One such expression is the late but effective #metoo movement across South Korea: in just a few months, dozens of leading politicians, business leaders and cultural personalities have been revealed as sexual abusers and rapists, shaking up the country’s traditionally “macho” culture marked by traditional ideas surrounding the separation between male and female roles.

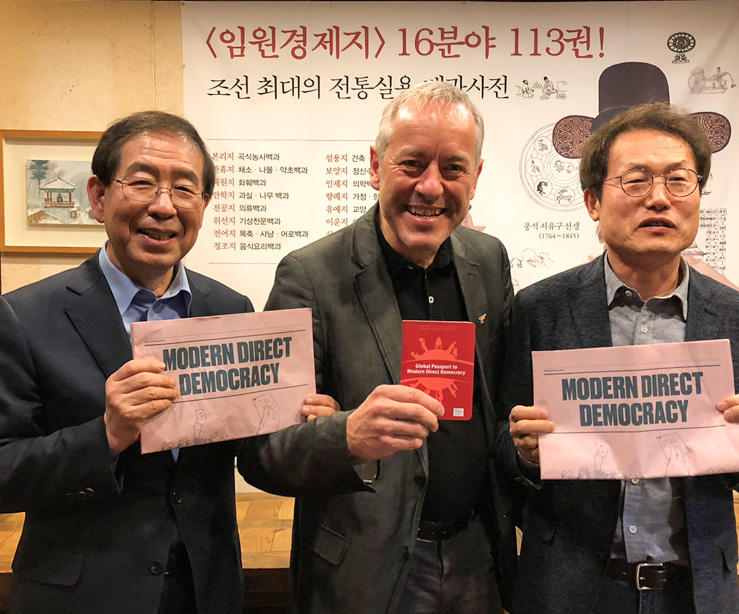

“Today we need to make all participants of the society responsible co-owners of our cities, regions and the country,” said Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon, another democracy activist- turned-political leader in Korea.

During a meeting with him and his education superintendent, Cho Hee-yeon, I learned more about the democratic eagerness of Korea’s new leaders – but also their very modest expectations when it comes to making progress.

“We need another hundred years,” says Park Won-soon, who will run for a third term in the upcoming city mayoral election on June 13. The very same day, a popular vote was planned for the new direct democratic constitution, the details of which continue to be fought in the halls of government.External link

The heated debate shows that despite all its progress and commitment, South Korea remains a divided country and society. The mostly younger and urban-dwelling population embraces new opportunities while many older people in rural areas embrace a more conservative viewpoint.

The conservative representatives in the National Parliament announced this week that they will do whatever they can to stop the constitutional reform process, the June 13 referendum and the introduction of modern direct democracy at the national level.

As of today, local citizens’ initiatives are purely advisory and popular votes at the national level are initiated by the president and parliament as plebiscites.

At this stage, it will require a lot of wise leadership to make the requested democratic progress feasible. Navigating upcoming talks between the two Koreas will perhaps require even more of the South’s leaders. But it is action time in South Korea now, hopefully for the good of all people in the country – and beyond.

Swiss-Swedish author and journalist Bruno Kaufmann last October set off on a world tour to explore the state of democracy visiting more than 20 countries on four continents until May this year.

swissinfo.ch has been publishing a weekly Notebook and multimedia reports by Kaufmann as part of its coverage of direct democracy issues.

Kaufmann’s democracy world tour is mainly sponsored by the Swiss Democracy FoundationExternal link, where he is the director of international cooperation. The Swiss Democracy Foundation hosts various projects and platforms linked to participatory and direct democracy across the globe, including Democracy International, External linkthe Direct Democracy NavigatorExternal link and the Initiative and Referendum Institute Europe.External link

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.