Why Colombia’s peace plebiscite failed

Everything about Colombia’s plebiscite for peace was unexpected. Not just the dramatic result – a rejection of the peace deal between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) that was supposed to end 52 years of civil war.

Pundits in and out of Colombia never imagined the deal would be voted down, but the outcome was hardly inexplicable. The reason for the outcome was not, as official advertising in favour of the referendum for the peace deal insinuated, that those campaigning for a No “want war.”

Nor was there any truth to the claim, advanced in the violent rhetoric of the opposition campaign, that those who voted Sí were “surrendering to terror”.

I’m a Uruguayan political scientist, based in Chile, who studies plebiscites, referendums and other forms of direct democracy in South America and around the world. And the failure of the referendum, while historic, is hardly new or without precedent.

As to the question of the peace deal itself, many Colombians refused the government’s premise that the only alternative to this peace deal was a continuation of violence.

The deal included plans for reintegrating former guerrillas into society that were deemed too lenient by a significant slice of a Colombian electorate fed up with the FARC. Almost all Colombians wanted peace, but disagreed over whether the accord amounted to a necessary political settlement or unwarranted amnesty for criminals.

But beyond the merits or demerits of the peace accord, the No’s triumph was also the product of government manipulation of the plebiscitary process that is all too common in direct democracy.

And, paradoxically, the manipulation occurred in in the context of a plebiscite that was institutionally unnecessary. The government was not required to submit this referendum to people; it chose to.

Manipulation

What’s the story behind this manipulation – and the boomerang against the peace deal? It’s important to start with the recognition that even in the best democracies, all electoral acts, be they to choose our representatives or to decide a matter via a direct vote, can be abused.

Robust democracies have a number of institutional mechanisms – from poll observers to full and free media coverage – that can counter such attempts to abuse the process. But there is no perfect system.

Modern direct democracy is open to manipulation. You can bias a vote in how you draft the question that is put to voters. Sometimes the campaigning and civic discussion can happen too quickly.

The design of the election, from how polling places are selected to how public employees deal with voters and ballots, can be changed to favour one side or another.

Deep media bias can also be a factor, with one side able to flood the public with information, overwhelming contrary information and opinions.

More

Colombian peace deal deposited in Bern

Severe problems

In the run-up to the Colombia plebiscite, the manipulation included all of these elements, simultaneously. Some problems were particularly severe.

The question posed to voters was clearly biased in favour of the peace deal: “Do you support the final agreement to end the conflict and the construction of a stable and long-lasting peace?”

There was little time for discussion or decanting of ideas and positions. The election institution tinkered with the process — specifically the quorums for participation and approval — to seek advantage for the Sí side.

The state was not neutral on the question; public employees were allowed to be actively for only one of the options. And finally there was an advertising blitz that amounted to emotional blackmail: if you vote No, voters were told, you wanted to the continuation of conflict.

Put all these issues together, and Colombia’s plebiscite couldn’t pass the minimum test of democratic fairness.

Public sentiment

The self-righteous nature of the government’s campaign in favour of its accord led many voters inclined to vote No to avoid tipping their hands prior to the election.

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos was awarded this year’s Nobel Peace Prize on Friday for his efforts to end the civil war.

The Norwegian Nobel Committee said the award should be seen as a “tribute to the Colombian people and to all the parties who have contributed to a peaceful solution.”

The referendum was not a vote for or against peace, but a decision against a specific accord, it added.

The committee said it hoped that the peace prize will Santos strength to succeed in his demanding task.

As a result, pollsters failed to capture public sentiment.

Imagine a typical average voter with some sympathy to the option No, because of concern about the particular terms of this peace deal. If that person had government business, he or she would find public employees wearing the “Sí” logos, with doves, in any public office. “Sí” posters supporting the deal would be all over the office.

And said voter would be inundated by the yes doves in the street and in the extensive media propaganda. The voter could use Uber for free to get to a voting place if he or she entered the right code, “Queltalsi” (“What About a Yes”)

New Venelzuela

At the same time, the opposition was hardly without sin; it offered a wicked campaign, backed by some of the society’s most reactionary sectors, that argued the government, through the peace deal, was delivering the country to the terrorists of FARC.

The government was accused of appeasement, and the opposition raised the spectre of the peace deal turning the country into a new Venezuela.

In the face of such pressure, the polite and expedient social norm among many Colombians before the plebiscite (as your mom used to warn you about other people), was to say nothing about the peace accord if you had nothing to say.

The simplistic messaging on behalf of the “Sí” as a vote for peace got in the way of an honest pitch for the details of plan.

Inevitable

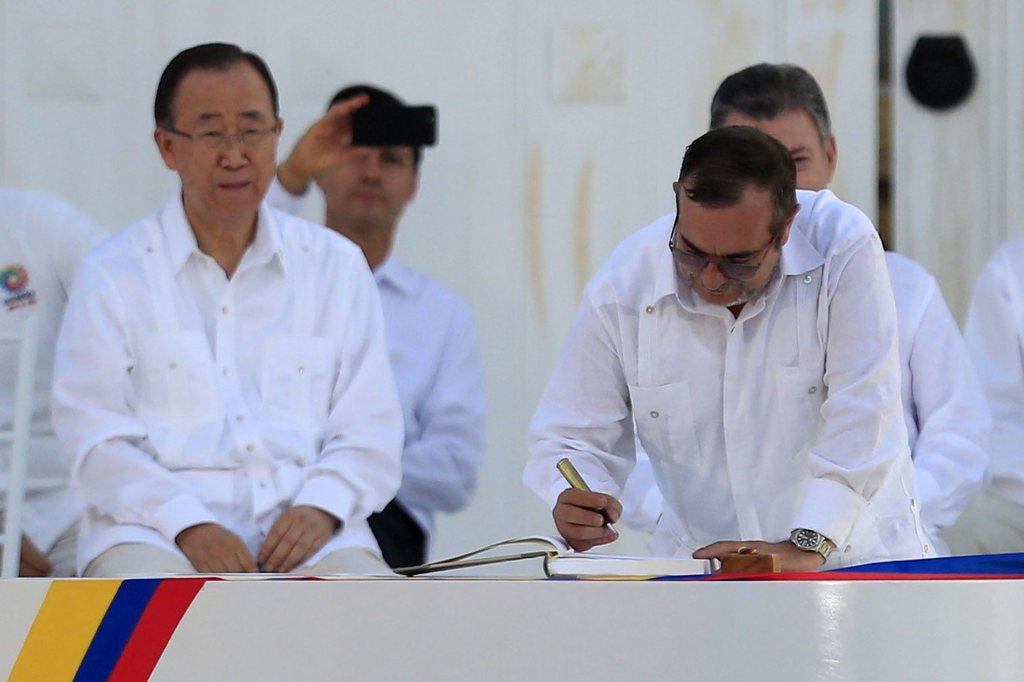

The government itself seemed to believe its own propaganda, that a vote for the deal was inevitable. Witness the world preview party in Cartagena for the vote, attended by United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and authorities around the world, all celebrating the end of violence.

The vote’s outcome was seen as a fait accompli. It was this impression of a fait accompli that led to the defeat.

Actually, the way in which the plebiscite was being sold was backfiring under the surface.

For one thing, why go to vote Yes if the vote is all but certain? In the end, turnout was less than 37% of Colombia’s electorate of nearly 34.9 million, with just 6.38 million voting yes, or 18% of eligible citizens.

Far from ideal

For another, it’s possible that some people who might have voted Yes with huge doubts, assuming a clear victory for the yes, felt comfortable voting no as a way of expressing that the agreement is far from ideal, in the belief they wouldn’t harm the final results of the plebiscite.

The government was guilty of not living up to Colombia’s status as a democracy. It failed to give the minimum consideration to the opposition, much less respect.

The vote would have gone better if the wording of the question and the media coverage had been balanced, if the quorums had not been touched, and if public employees had been barred from campaigning so actively.

Arrogance

Colombia’s leaders were guilty of haste, pride and arrogance.

The governmental triumphalism led to celebrations long before the vote. Fans of Colombia’s national football team should have known better—a victory should never be celebrated before the referee blows the final whistle.

This triumphalism combined with the opposition’s fear-mongering campaign to create uncertainty: in the face of such anxiety, the status quo tends to thrive, as we know from considerable research.

Understanding the context of this plebiscite, the social media reaction that Colombia “lost the peace and won the war” is clearly absurd and reductionist.

Peace did not lose—this particular agreement did.

It’s time to try again, and bring forward a peace agreement in a fair referendum that can enjoy the support of a majority of Colombians, not just the 18% of eligible citizens who voted yes.

This text first appeared on the People2PowerExternal link platform on direct democracy, hosted by swissinfo.ch. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of swissinfo.ch.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.