Why people are for – and against – a new national park

A local citizens’ initiative to set aside a mountainous corner of Switzerland as the country’s second national park could fail to win support at the very level it began, the grassroots.

A couple of chickens cross the road in Hinterrhein, the last village on the road up to the San Bernardino alpine pass in the southeast. Otherwise, all is quiet. The sign on the Bachhuus Chäller restaurant says ‘open’ but no guests appear to be inside.

Many Swiss towns and cities, from Geneva to Zurich, are full to bursting with housing at a premium but villages like Hinterrhein have trouble stopping residents from moving away. The village has lost a third of its population in the last ten years. Most of the 69 remaining are farmers.

It’s a clear, icy evening when a few dozen people from the village and neighbouring communes gather inside a large wooden shed on Hinterrhein’s outskirts. The promoters of Parc Adula have spent weeks visiting and lobbying the residents of the surrounding valleys to support the idea of setting up the new national park on their doorstep. A majority of voters in at least 13 of the 17 communes must say yes if it’s to go ahead.

More

Alpine vistas of proposed national park

Not just winning or losing

“It’s not just about winning or losing a vote,” declares Hinterrhein’s mayor, Georg Trepp, at the beginning of the evening, “it’s about our future!”. He’s convinced that once declared a national park, Parc Adula’s farmers will have an easier time marketing their produce, which in turn will stop the exodus from the villages.

But there is significant opposition among locals, who fear national park regulations will impose too many restrictions on their lives. One person who is in favour of the park’s creation is not afraid to acknowledge that environmental organisations could use every legal means at their disposal to stop any new construction, even that of a barn.

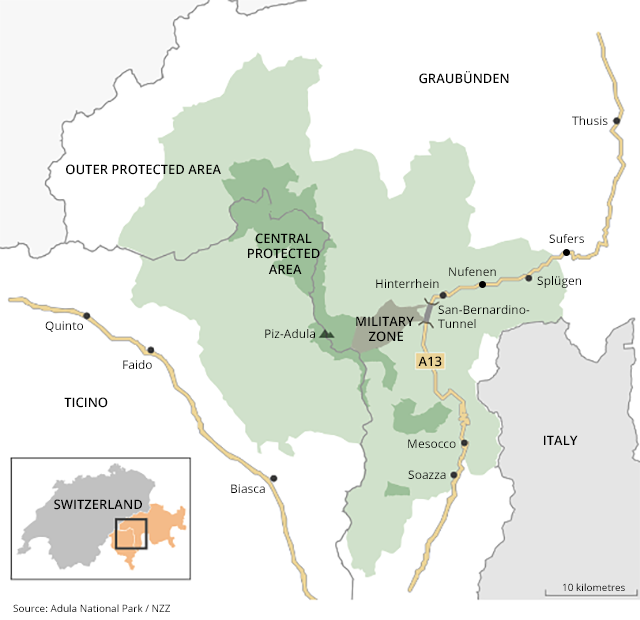

The promoters have come prepared to counter such arguments. The president of the pro Adula association, Fabrizio Keller, explains that the new park won’t be placed in the same ‘hands off’ nature reserve category as Switzerland’s only existing park. Keller says only the core zone will be given absolute protection. Inhabitants will for the most part be able to go about their business as usual in the outer, larger zone.

The project initiators are at pains to emphasis that Parc Adula is a ‘bottom up’ project, not a plan decreed by the federal authorities.

Million-franc reward

It was in 2000 that the environmental organisation, Pro Natura, launched a competition to award CHF1 million ($1 million) to the founders of a second national park. Keller repeats this anecdote to the gathering, recalling how a few representatives from the local communes got together to discuss whether this could be the answer to the region’s problems.

This small corner of the country is a miniature Switzerland. Even though there are only 16,000 inhabitants, they are from three of the country’s four language communities (German, Italian, Romansh) and the communes they live in are spread across two cantons.

The wheels of democracy turn slowly when so many communities and diverse groups are involved. It took 15 years just to agree the future park’s charter. When it was finally presented at a town hall meeting, it was met with more than 700 claims, petitions and motions.

In one case, a village requested that a small part of the park it administered be removed from the core zone. In another, the federal government intervened since an army shooting range was originally situated in this highly protected area. Some inhabitants demanded more hiking trails while there were calls by environmental groups and game wardens for fewer.

“We’re not selling our soul to the devil, nor to the WWF or Pro Natura,” says the Adula association president, in an attempt to allay fears and to emphasis that it will be the communes, and not the federal government, running the park. “We want to give the next generation a chance to stay here.”

No one asks for such basic information at the meeting – they’re too well prepared for that. Instead, they demand details: When will winter regulations for the park end and the ones for summer begin, is one example. “It will be change from year to year,” is the answer.

Another citizen would like to know how many jobs the park will create. Eighteen is the answer.

After an hour, all the questions have been fielded and the discussion continues informally over beer, wine and orange juice.

If a majority of citizens in at least 13 of 17 communes say yes when they go to the polls on November 27, the two cantons that will be impacted – Graubünden and Ticino – will submit a request to the federal authorities to recognise the new national park.

If approved, they will receive a licence to operate the park for ten years – with an extension requiring approval again at the ballot box. If voters say no this Sunday, then the communes that were in favour have the option of drafting a new proposal to be put before the people.

Do you think creating a national park is worthwhile? Tell us in the comments section below.

You can contact the author @SibillaBondolfi on FacebookExternal link and TwitterExternal link.

Translated from German

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=8f77363a)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.