Does your vote count? Trump says ‘Let’s see’ – Switzerland says ‘Let’s talk…’

America’s election anxieties are far from unique. Switzerland’s recent referendum experiences may offer some clues for managing polarisation.

In a scary moment for American democracy, US President Donald Trump declined to say if he would accept the outcome of the November 3 election, warning his supporters to prepare instead for a democratic disaster.

“This is going to be a fraud like you’ve never seen,” he said during the first debate between himself and Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden.

Trump also questioned the fairness of mail-in voting – which began in the 1880s and is now accessible to 83% of the US electorate – and suggested the “Proud Boys” white supremacist group should “stand by” until the result is known.

This lurch towards anti-democratic behaviour in the oldest modern democracy is hardly an outlier in the global political landscape, according to New York University Professor of Politics Adam Przeworski. He counts 68 countries that have never yet had a peaceful handover of power.

“In fact, peaceful transitions of power and acceptance of ballot decisions have been rare in modern states,” he says, citing his research into 3,000 popular votes across 230 years. In Africa, a special prizeExternal link aims to honour leaders who willingly step down in the face of democratic opposition. It was symbolically conferred on Nelson Mandela in 2007, but it has not been awarded in six of the last ten years because the international jury could not find one leader on the African continent who was prepared to accept a democratic defeat.

Electoral defeat should not be a bug but a feature

Such an unwillingness to concede an election or referendum is “a clear sign that democracy is too weak in a country,” says Marc Bühlmann, a political science professor at the University of Bern. “In a genuine democracy defeat does not exist, just results.”

In many countries the ballot box is not just a regular check on power; it helps to give balance to a variety of competing interests. The US Constitution deliberately sets up a tension between the presidency and Congress, which are often controlled by opposing parties. In Germany, elections in each of the 16 BundesländerExternal link (states) are spread over the five-year term of the Bundestag, the lower house of parliament, enabling voters to fine-tune the power balance in the Bundesrat, the upper house where the states are represented. The French sometimes live with “cohabitation”: a president from one side of politics and a government from another. These kinds of power-sharing and compensating mechanisms can make it easier for a political camp to accept a negative result at the polls.

This also holds true for Switzerland.

“A powerful illustration of this ballot acceptance culture was the most recent referendum on September 27,” said Bühlmann, who leads the SwissvotesExternal link research project, assessing all ballot results since 1848.

More

Vote results: September 27, 2020

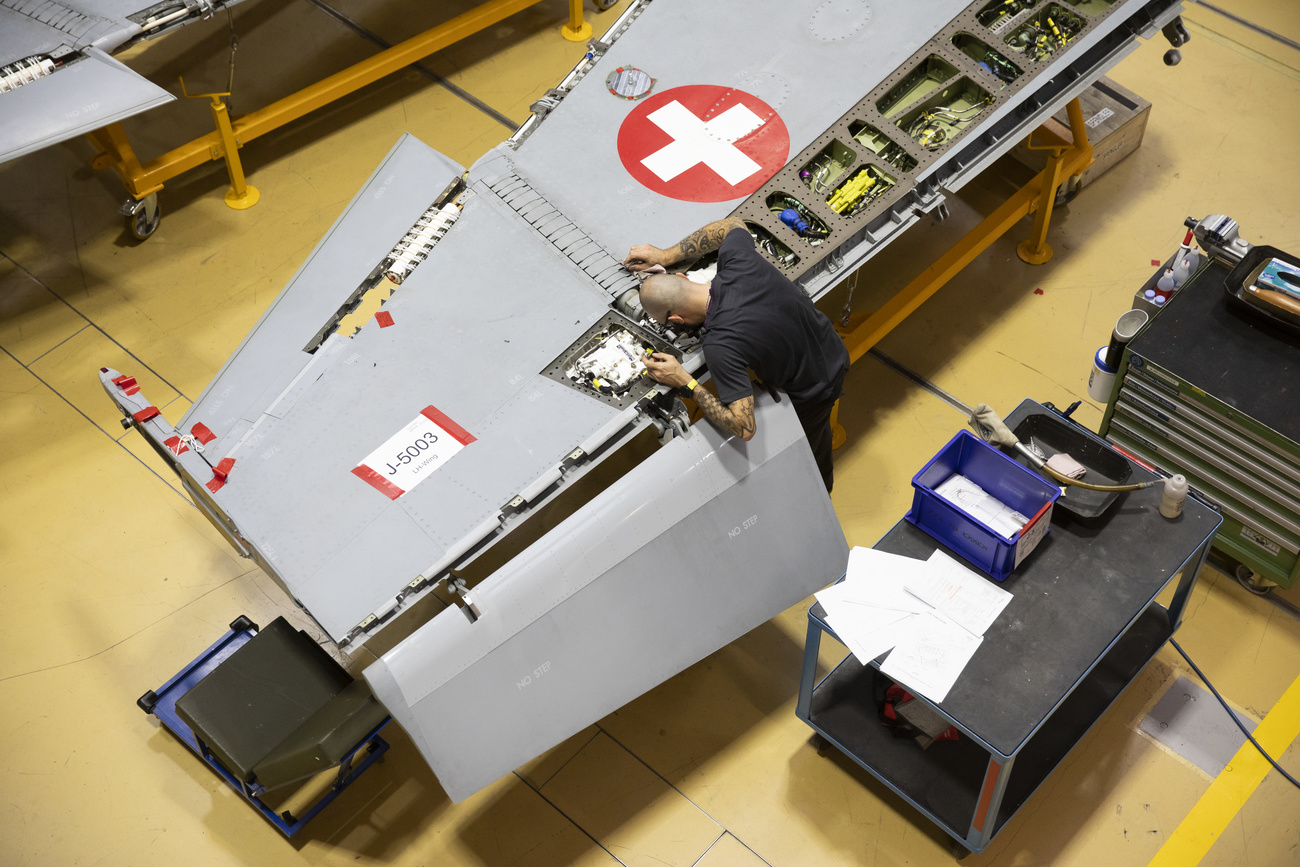

There was a rare cliffhanger as results came in from across the country for the five issues on the ballot. At the Dübendorf Air Force CenterExternal link, a museum displaying former Swiss air force planes, TV cameras were cued up as rival campaigners braced for the public’s verdict on whether to spend CHF6 billion ($6.6 billion) on a new fleet of jets. But the initial numbers showed a 50-50 split and politicians’ prepared statements had to wait for several hours. Eventually the pro-jet side won a tiny majority: fewer than 9,000 votes out of more than three million ballots cast. Despite her side “winning”, Defence Minister Viola Amherd immediately conceded that a future purchase may be “cheaper than planned”, while the “losing” side that had been against the purchase announced plans for a new citizens’ initiative on the type of aircraft to be bought. In other words, the vote did not end the conversation.

“Possibly, the government’s responsiveness towards voters’ needs, meeting the opposition halfway, might prevent a new ballot,” says Giada Gianola, a political scientist at the University of Bern. The Swiss political system offers many avenues for citizens and political groups to set the agenda and be part of the decision-making process, she notes. “After the most recent referendum experiences we can already see new ballot proposals on the issues of parental leave, the hunting law and the question of European integration.”

All three items were already voted on during the September 27 referendum.

The Swiss have a right to be heard (frequently)

Not all Swiss voters appreciate being asked to weigh in on political battles three or four times a year, and there have been efforts in parliament and by cantonal governments to introduce waiting periods for new citizens’ initiatives.

“Such limitations and waiting periods exist in many countries with direct democratic mechanisms,” said Klaus Hofmann, editor of the Direct Democracy NavigatorExternal link at the University of Wuppertal, who has catalogued more than 1,800 legal frameworks for referendums and initiatives in 108 countries. But the Swiss federal government has long rejected any attempt to limit the citizens’ ability to launch initiatives and referendums.

“The lack of such barriers has never led to intolerable disruptions or tensions in public life,” the government argued in 1986, responding to a proposal by a liberal parliamentarianExternal link from Basel, who – as an employee in the chemical industry – was angry that an initiative to limit animal testing was launched one day after a referendum vote on a similar proposal.

A way to overcome polarisation?

Direct democracy can thus reduce the “winner takes all” philosophy at the ballot box. And such methods do exist in the United States, although not at a national level.

Sarah Rosier at BallotpediaExternal link, an online database of US ballot measures, notes that 49 of the 50 US states have a way to send new laws or constitutional amendments to a public vote via their legislatures.

“Twenty-five states allow the citizens themselves to request a referendum on new laws,” she adds.

“Our big problem is that we have no direct democracy on the federal level,” says Dane Waters, a Republican party strategist and former Republican administration official.

“America is now facing one of its greatest tests since the Civil War,” he estimates. “Division and polarisation is at its zenith and all rooted in racial, economic, moral and social differences. If the US had direct democracy at the national level these differences could have been addressed […] by giving people a voice.”

More

National security and the ballot box: an odd couple around the world

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!