Flu shot debated ahead of vaccinations

As Switzerland prepares to roll out a national campaign for vaccines against the H1N1 virus, opinion is divided on whether mass vaccinations are really necessary.

The government will outline its mass immunisation plans on Friday in a joint press conference given by the Federal Commission for Vaccinations, the medical supervisory agency and the Swiss Medical Association.

Two vaccines are expected to be given the go-ahead by Swissmedic, which has been overseeing trials of the brands in laboratories in Switzerland. Further details of the vaccination campaign are being kept under wraps until then.

Whatever the outcome, one doctor has vowed he won’t be taking part.

Pascal Büchler, a family doctor in Yverdon-les-Bains and member of Infovaccine, a group of doctors raising awareness about the effects of vaccines, says the H1N1 vaccine has not been sufficiently tested and is being introduced too early.

“It was a vaccine that was produced very quickly. We do not know its effectiveness and how innocuous it is,” he told swissinfo.ch.

He explained that the European Medicines Agency authorised H1N1 vaccines to go on sale under “exceptional circumstances” – for which the World Health Organization (WHO) current pandemic level six qualifies. The agency states that clinical trials of H1N1 vaccines have been limited to adults and the elderly, and the long-term significance is not yet known.

With long-term effects and rare side-effects unclear, Swissmedic has set up a webpage where results of the vaccines will be posted and on-going effects monitored.

“The problem is that we’re not going to vaccinate a few people and see if there will be a few secondary bad effects,” Büchler said.

“If we vaccinate 2,000-3,000 people, we can stop quite quickly if we discover a serious side-effect in these people. If we immediately vaccinate ten million people, the outcome could be dramatic.”

He added: “Personally I refuse to issue this vaccine. I find it goes against the first rule of medicine, which is not to cause harm.”

Essential ingredient?

Switzerland has ordered 13 million doses of the vaccine from GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis.

Until now the health authorities have recommended vaccination only for at-risk groups: health workers, pregnant women, children aged six months and older, adults with certain medical conditions and elderly people suffering from severe illness.

The Swiss campaign will follow mass vaccination moves in the United States and Britain. On Saturday, President Barack Obama declared the H1N1 outbreak a national emergency, giving his health chief the power to let hospitals move emergency rooms offsite to speed up treatment. Around 1,000 people have died from the virus in the US.

Britain launched its national vaccination campaign on Wednesday. It is the country worst affected by H1N1 in Europe, with around 53,000 new cases reported last week. In Switzerland there have been around 1,400 cases to date, one serious and no deaths.

Ahead of the campaign Swiss media have reported concerns over whether safety has been compromised in the rush to develop a vaccine. Among the issues is the use of adjuvants, a chemical compound that stretches a vaccine’s active ingredient and increases the human body’s immune response.

European flu vaccines commonly use adjuvants, but there is limited data on how safe they are in groups including children and pregnant women. In the US, no seasonal flu vaccines with adjuvants have yet been tested and approved.

“Unpleasant but benign”

Pietro Vernazza, medical director of St Gallen cantonal hospital, tested one vaccine’s AS03 adjuvant on himself and found that his arm hurt and he had a bad night’s sleep.

“The currently or soon-to-be available vaccines have managed to produce an excellent immune response and for that purpose a good adjuvant is needed,” he said.

“Of course, you can also just use much more virus and get a stronger immune response, but you cannot produce a good immune response without any local side effects, i.e. without immune-stimulation.”

Claire-Anne Siegrist, president of the Federal Commission for Vaccinations, told swissinfo.ch: “It’s normal that people have questions and concerns because it’s all very new. Six months ago, these people did not know what an adjuvant was, and now they are afraid that it is even more dangerous than the flu.”

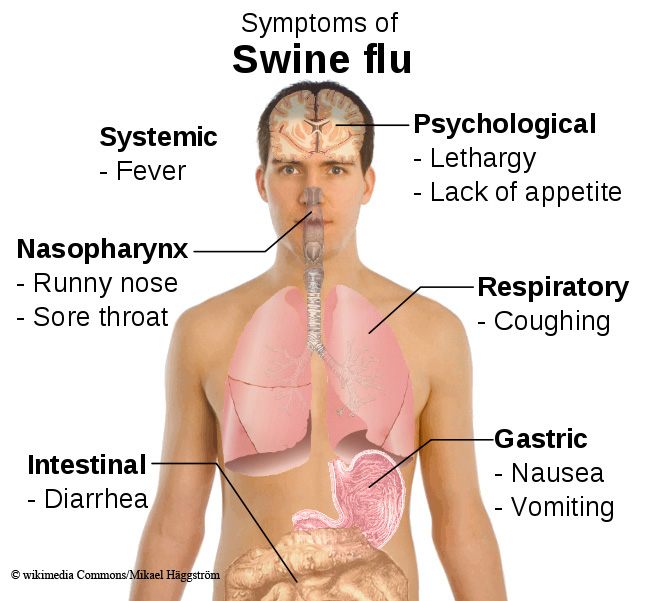

She noted that studies carried out with adjuvants over the past year and with H1N1 this summer had shown side-effects of swelling and soreness at an injection spot, or in worse cases, headaches, fatigue and fever.

“It’s unpleasant but benign compared with the risks of complications of flu in at-risk groups,” she said, adding she believed the vaccine was also safe for pregnant women and babies.

“If my daughter was pregnant now or I had grandchildren with health problems, I would not hesitate to ask them to take an MF59 adjuvant vaccine.”

Jessica Dacey, swissinfo.ch

More

Pandemic

Switzerland has ordered 13 million doses of H1N1 flu vaccine from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline. They are being tested by Swissmedic, which will announce on October 30 whether the vaccines are approved for mass immunisation in Switzerland, in a campaign that should get underway in November.

Both vaccines contain an adjuvant called squalene, a natural organic oil which promotes good antibodies.

Novartis’s vaccine was cultivated from dog kidney cells containing the adjuvant MF59 which consists of a mixture of water and squalene. Squalene has been used for 12 years as an adjuvant for the seasonal influenza vaccine Fluad.

GlaxoSmithKline’s vaccine uses squalene and polysorbate, a vitamin E derivative. Their adjuvant was tested in extensive clinical trials for the pre-pandemic vaccine based on the bird flu virus, H5N1.

According to Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline, side-effects are similar to those of seasonal flu vaccines: a swelling and redness at the injection site and fever, limb pain and headache.

This swine flu variation, termed H1N1, is an influenza A virus spread from person to person.

It contains DNA from avian, swine and human viruses. Although swine flu viruses normally infect only pigs, they do sometimes cross the species barrier to cause disease in humans, according to the WHO.

It is passed from human to human by sneezing, coughing or by hand contact. The WHO says swine flu is not transmitted to people eating properly handled and prepared pork or other products derived from pigs.

New flu strains can spread fast because no one has natural immunity and a vaccine can take months to develop.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.