Recognising Switzerland’s “slave children”

In a practice that lasted in Switzerland until 1981, tens of thousands of children and teenagers were forcibly removed from their families, who for one reason or another were deemed by the authorities to be incapable of caring for them.

It is a chapter in Swiss history that has left painful scars. Now victims of these measures have been invited to a “ceremony of commemoration” in Bern on Thursday.

“I was born without a father and my mother gave me to my grandmother to look after. When my grandmother died, they placed me with the sisters and then with a farmer. I had to milk the cows before going to school and he treated me very harshly. I was nobody,” Paul Stutzmann recalls.

He later went on to become a craftsman specialising in windows, including stained glass. In addition to having six children of their own, Stutzmann and his wife took in two more from a relative who was unable to care for them.

Now 72, Stutzmann was one of an estimated 100,000 children subjected to the policy in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Effectively a cheap labour force, the children were sometimes beaten, malnourished, or sexually abused. For their part, unmarried teenage mothers and dropouts could be detained without trial or interned in psychiatric hospitals right up until the 1980s. The authorities sometimes even decreed that the adults should be castrated or sterilised and forced to hand their children over for adoption.

In the early 2000s, survivors’ accounts began to appear in the media, triggering questions in parliament. For a long time, the churches, cantons, communes, and government all blamed each other – some even playing down the mistreatment suffered by the children.

The situation began to change in 2010 when, following heavy lobbying, women who had been detained without trial in the Hindelbank prison in canton Bern obtained an official apology from federal and cantonal authorities.

This week’s historic commemoration, to be attended by Justice Minister Simonetta Sommaruga, will for the first time bring together all those involved in the policy including representatives from the institutions, churches, cantons, towns and the Swiss Farmers’ Union. Former federal parliamentarian Hansruedi Stadler has been nominated by the minister to mediate future discussions between the victims and institutions.

More

Home, unsweet home

Too ashamed or too painful

“At the time, it was normal to mistreat the children and poverty was considered a flaw to be corrected with hard work. I was invited one day to a meeting of these people and I was so completely shocked by what they said that I was speechless,” says Walter Zwahlen, president of the Association for Stolen Children.

It is estimated that around 10,000 of these children are still alive but Zwahlen’s association has only about 40 members.

“Many are too ashamed to come forward and it is too painful to reopen the old wounds,” he says.

Because the archives of these events are dispersed between the cantons, communes and institutions, or have even been destroyed, there has not yet been a national study undertaken of the practice. As a result, oral testimony is practically the only reliable source to document what happened. Nevertheless, Zwahlen has developed a unique library of 620 books of testimony from a range of countries where similar practices were carried out.

“It was the same elsewhere,” he explains. “There is just as little documentation as in Switzerland but the witness accounts are the same from Germany to Poland to Czechoslovakia or Norway.”

Although there have not yet been any scholarly studies into how children in Switzerland were brought up outside their families, it is officially acknowledged that, until 1981, children and young adults in need of care were forcibly placed in institutions or on farms.

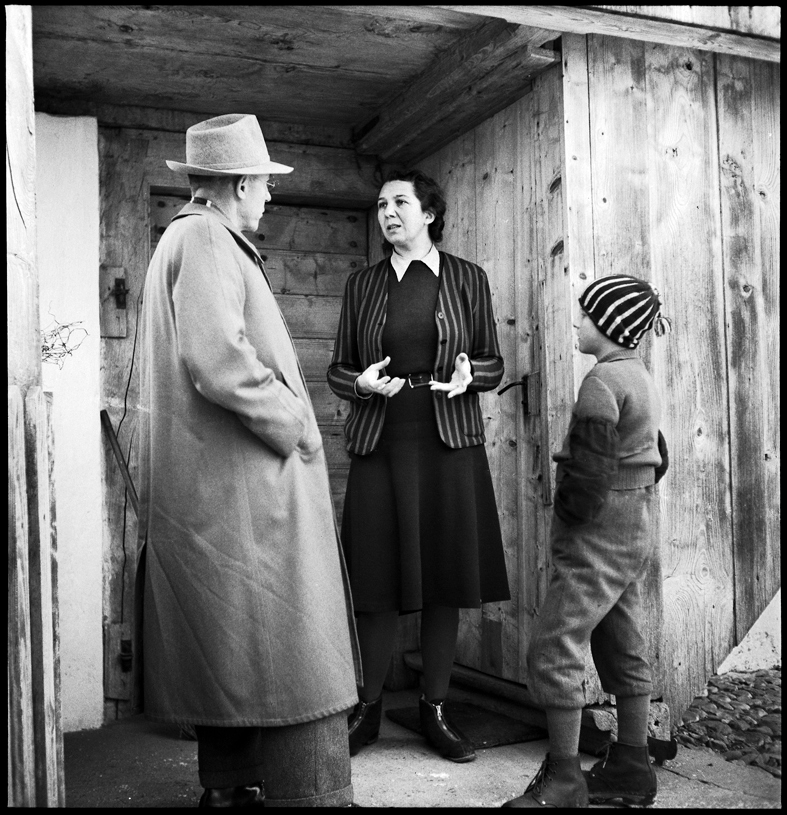

1944: the weekly journal Die Nation published an investigation into the boys’ home at Sonnenberg in canton Lucerne by the journalist Peter Surava and photographer Paul Senn. The institution was later closed and its director convicted of mistreating the boys.

1974: journalist and politician Arthur Honegger published a partly autobiographical novel about the forced placement of children, which sold more than 100,000 copies.

1981: seven years after the ratification of the European Convention on Human Rights, clauses were added to Swiss law was to cover deprivation of liberty for the purpose of social assistance.

1991: Bern historian Marco Leuenberger, whose father was a victim the forced labour policies published the first, and to this day, only, wide ranging study of such practices in canton Bern.

1999: a parliamentary initiative calling for compensation for victims of forced sterilisation was lodged. So far it has come to nothing.

2009-2013: the travelling exhibition “Enfances volés – Verdingkinder Reden” (Stolen Childhoods) consisting of nearly 300 stories and photos, has been seen by some 85,000 people across Switzerland.

So far, cantons Bern, Lucerne, Fribourg and Thurgau have officially apologised for the practices.

In 2010 following a parliamentary inquiry, the then Justice Minister Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf apologised for the incarceration of innocent women at the Hindelbank prison in canton Bern.

2011: two parliamentary motions were tabled; one calling for the rehabilitation of victims, and the second for the government to face up to what had happened and to issue an apology to the children involved.

Years of pressure

“We can no longer ignore the fact that it happened. Many families have members who were farmed out,” says researcher Pierre Avvanzino, former professor in the social work division at the University of Applied Sciences in Lausanne.

“In 1987, the travellers’ children taken from their parents were rehabilitated and received compensation. This was easy because the ‘children of the road’ programme [1926-1973] was mandated at a federal level. The archives were centralised, so that it was impossible for the government to avoid either apologising or providing compensation!”

For the children who were forced to work on farms or and those detained without trial, it took years of pressure – including hunger strikes, appeals to the European Court of Human Rights and a travelling exhibition which began in Switzerland in 2009 – before a few cantons (Bern, Lucerne, Thurgau and Fribourg) issued apologies for past practices.

Two parliamentary initiatives are now calling for moral reparation and the launch of a national research programme. But the question of financial compensation is off the table for the rightwing parties and for most of the members of the judicial committee of the House of Representatives.

The billion franc disagreement

An economist from a large bank, working with the daily tabloid Blick, recently calculated that “the unpaid labour of children was worth between CHF20-65 billion to the agriculture industry. The some 10,000 children still alive should be eligible for around CHF1.2 billion ($1.6 billion).”

For Zwahlen, it’s a realistic figure, but while the Swiss Farmers Union has acknowledged “this dark chapter in Swiss history”, it rejects both the idea of an apology or compensation.

“It’s difficult, even impossible, after so many years, to fix an amount and any lump sum compensation could not take into account the conditions of the children which were different from case to case,” says union president Jacques Bourgeois.

Avvanzino is also sceptical: “It would take a lot of political pressure, something I don’t see for the moment. Only a few people see it as an issue. The historical facts are still too disputed and, in my opinion, these children don’t count for anything for politicians. But if we want to do something, it has to be done quickly because these people are dying off.”

So will Stutzmann go to Bern on Thursday?

“I don’t think I have the nerve. And then, I’ve had a good life. For me, all this is in the past, it’s over and done with,” he says somewhat hesitantly.

(Translated from French by Sophie Douez)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.